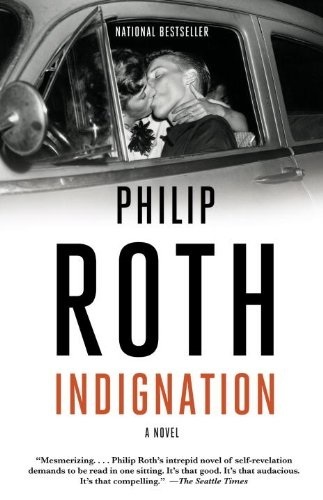

From “The Human Stain” to “The Humbling,” Philip Roth adaptations are a tough sell. Brooding, yet devoid of the author’s rich insights, these films often die on the vine. “Indignation” is a rare exception, partly because the eponymous 2008 novel is an unusually lean, plot-driven effort for Roth. (It’s no coincidence that “Goodbye, Columbus,” his most successful adaptation, is also uncharacteristically plot-driven.) Partly too, this is the first feature by writer/director James Schamus, who wrote the screenplays for “The Ice Storm” and “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,” and, as the CEO of Focus Pictures, was responsible for such elegant indies as “Far From Heaven” and “A Serious Man.” In watching this meticulously crafted film, I get the sense Schamus would have waited forever for the perfect project for his debut. This is not to say this film is perfect – it is too dour to qualify as perfection – but every frame speaks of an unflagging, ultimately winning dedication.

From “The Human Stain” to “The Humbling,” Philip Roth adaptations are a tough sell. Brooding, yet devoid of the author’s rich insights, these films often die on the vine. “Indignation” is a rare exception, partly because the eponymous 2008 novel is an unusually lean, plot-driven effort for Roth. (It’s no coincidence that “Goodbye, Columbus,” his most successful adaptation, is also uncharacteristically plot-driven.) Partly too, this is the first feature by writer/director James Schamus, who wrote the screenplays for “The Ice Storm” and “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,” and, as the CEO of Focus Pictures, was responsible for such elegant indies as “Far From Heaven” and “A Serious Man.” In watching this meticulously crafted film, I get the sense Schamus would have waited forever for the perfect project for his debut. This is not to say this film is perfect – it is too dour to qualify as perfection – but every frame speaks of an unflagging, ultimately winning dedication.

Newcomer Logan Lerman plays Marcus Messner, a Jewish scholarship student attending Ohio’s fictional Winesburg University during the Korean War. The school’s name is a nod to “Winesburg, Ohio,” Sherwood Anderson’s catalogue of small-town grotesques, which feels appropriate. Brilliantly economical, Marcus is a bomb-in-waiting, tormented by the mid-century hypocrisies he espies everywhere on his goyishe campus and hometown of Newark, where his butcher father is having a nervous breakdown triggered by neighborhood boys returning home in body bags. Much is riding on Marcus’s ability to keep his eyes on the prize, for he must stay in school if he wishes to beat the draft and fulfill his family’s dreams. Yet the anti-Semitism of his classmates, the moralistic bullshit of Dean Caudwell (the actor/playwright Tracy Letts), and the gleaming long legs of transfer student Olivia (Sarah Gadon, seemingly floating on air) make it hard for the locked-down boy to keep from erupting, even as he excels academically and at his work-study library job.

Marcus is so overwhelmed that he doesn’t detect Olivia’s similiarities to his increasingly disturbed father – he misses the faint scars on her wrists, the anxiety she covers with a WASP princess composure. It’s only when she ends their very traditional first date with a very untraditional hand job that he’s wrenched out of his shiksa fantasy. Her sexual assertiveness doesn’t jibe with the pedestal upon which he has placed her, and their romance falters.

What doesn’t lose momentum is the two-step he is dancing with Caudwell, who admires the younger man’s intellectual rigor but is repelled by his unorthodox values – ostensibly his atheism; really, his Jewish heritage. (Bring it, Roth.) Marcus’s rigorous personal code is not wired for deference, and the resulting face-offs between these two men read as thrilling theater without ever devolving into staginess, which is a tough note to strike on film. Words fly in rat-a-tat-tat storms that are as rhythmic as Sorkin’s or Mamet’s dialogue if far less aggrandizing. You don’t even find it melodramatic when Marcus’s appendix suddenly bursts.

by his unorthodox values – ostensibly his atheism; really, his Jewish heritage. (Bring it, Roth.) Marcus’s rigorous personal code is not wired for deference, and the resulting face-offs between these two men read as thrilling theater without ever devolving into staginess, which is a tough note to strike on film. Words fly in rat-a-tat-tat storms that are as rhythmic as Sorkin’s or Mamet’s dialogue if far less aggrandizing. You don’t even find it melodramatic when Marcus’s appendix suddenly bursts.

As he heals in the gentle white chambers of the school infirmary, this story grows more measured. As polished as the films Schamus has produced, it lets up in neither form nor function, though. With brocaded wallpaper, jade-green poodle skirts, and golden pooled light, it looks era-perfect, but unobtrusively so – like a sepia photograph on the back of your grandmother’s piano. If we watch its progress with some detachment, it is not just because we are shown the characters’ fates from the onset. It is also because this film is deeply, admirably unsentimental, with direction so seamless that only in the fine work of the actors is an agenda laid bare. In their trembling hands and breaking voices, we can foresee their explosions–they are of the sort that shape our country even today.

This originally appeared on Signature.