“Dangerous Liaisons,” Stephen Frears’s adaptation of Choderlos de Laclos’ 1782 epistolary novel about the sexual schemings of the French pre-revolutionary upper crust, was released in 1988. This is fitting, for no decade of the twentieth century channeled the 1780s’ “let them eat cake” conspicuous consumption more overtly than the 1980s.

“Dangerous Liaisons,” Stephen Frears’s adaptation of Choderlos de Laclos’ 1782 epistolary novel about the sexual schemings of the French pre-revolutionary upper crust, was released in 1988. This is fitting, for no decade of the twentieth century channeled the 1780s’ “let them eat cake” conspicuous consumption more overtly than the 1980s.

By 1988, of course, an uncomfortable self-awareness was sweeping the United States and England—not only because of the 1987 stock market crash but because of the dawning realization that AIDS was here to stay unless conservatives like British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and U.S. President Ronald Reagan finally acknowledged it as a legitimate health crisis. The party was drawing to a close but such ridiculous glitz as big hair, blackened catfish, and gold lamé dresses still dominated the cultural zeitgeist. If you replaced the post-punk soundtrack with the trilling of opera and slitted your eyes just the right way, it all looked exactly like Marie Antoinette’s doomed palace.

It is also fitting that Stephen Frears directed this adaptation. In such earlier projects as “My Beautiful Laundrette” (1985), in which he introduced the angular genius of Daniel Day Lewis to the world, and “Prick Up Your Ears” (1987), about the ill-fated gay playwright Joe Orton, the helmer had established his fierce class politics through the medium of sexual politics. With “Liaisons,” he was in his element, then—allowed to eat his cake too.

Some criticized the casting of John Malkovich as Vicomte de Valmont, the most notorious cad of this aristocratic set. “He lacks the devilish charm and seductiveness one senses he would need to carry off all his conquests,” sniffed Variety. I thought his lack of prepossession helped. Malkovich in his mid-30s was nothing to sniff at, actually—his crossed eyes and wide hips were still eclipsed by a panther litheness, a mane of dark hair, a rosebud mouth tonguing consonants suggestively—but it’s the sense that his deficits gave him something to prove that really makes this Valmont click. Every frame explores avarice, in the most sadomasochistic, sociopathic connotation of the word. It is capitalism as sexual manifest destiny—as decadence at its most irresistible.

Of course, the film’s true core (if not heart) is the Marquise de Merteuil, as played by Glenn Close. By 1988, Close had already made her name playing femme fatales and fatal feminists; she’d killed bunnies in “Fatal Attaction,” and played a sex-positive abstinent nurse in “The World According to Garp” and a lawyer with lethal boundaries in “Jagged Edge.” With her oyster smile and furious, beady eyes, she was a shoe-in for the four-faced aristocrat who beds the prettiest of her peers before engineering their demise.

Of course, the film’s true core (if not heart) is the Marquise de Merteuil, as played by Glenn Close. By 1988, Close had already made her name playing femme fatales and fatal feminists; she’d killed bunnies in “Fatal Attaction,” and played a sex-positive abstinent nurse in “The World According to Garp” and a lawyer with lethal boundaries in “Jagged Edge.” With her oyster smile and furious, beady eyes, she was a shoe-in for the four-faced aristocrat who beds the prettiest of her peers before engineering their demise.

Her Marquise and Valmont make a deal: She’ll sleep with him if he deflowers Cecile de Volanges (a convincingly gawky Uma Thurman) before the 16-year-old virgin marries Merteuil’s former lover, and if Valmont seduces Madame de Tourvel (Michelle Pfeiffer), a married woman known for her high moral standards and even higher cheekbones. Clearly female solidarity is not Merteuil’s thing, though she seems to view herself as a female liberationist–the kind of self-serving “post-feminist” that the 1980s produced in unfortunate scads. She talks a good line— “I am a woman. I had to invent myself and ways of escape no one ever dreamed of”—but the rationalization she offers for her machinations— “I do not seek pleasure so much as knowledge” —does not ring as true as her cool correction of Valmont when he suggests she values betrayal above all else. “No,” she replies airily, as if refusing a cake. “No, I’ve always thought cruelty had a nobler ring.”

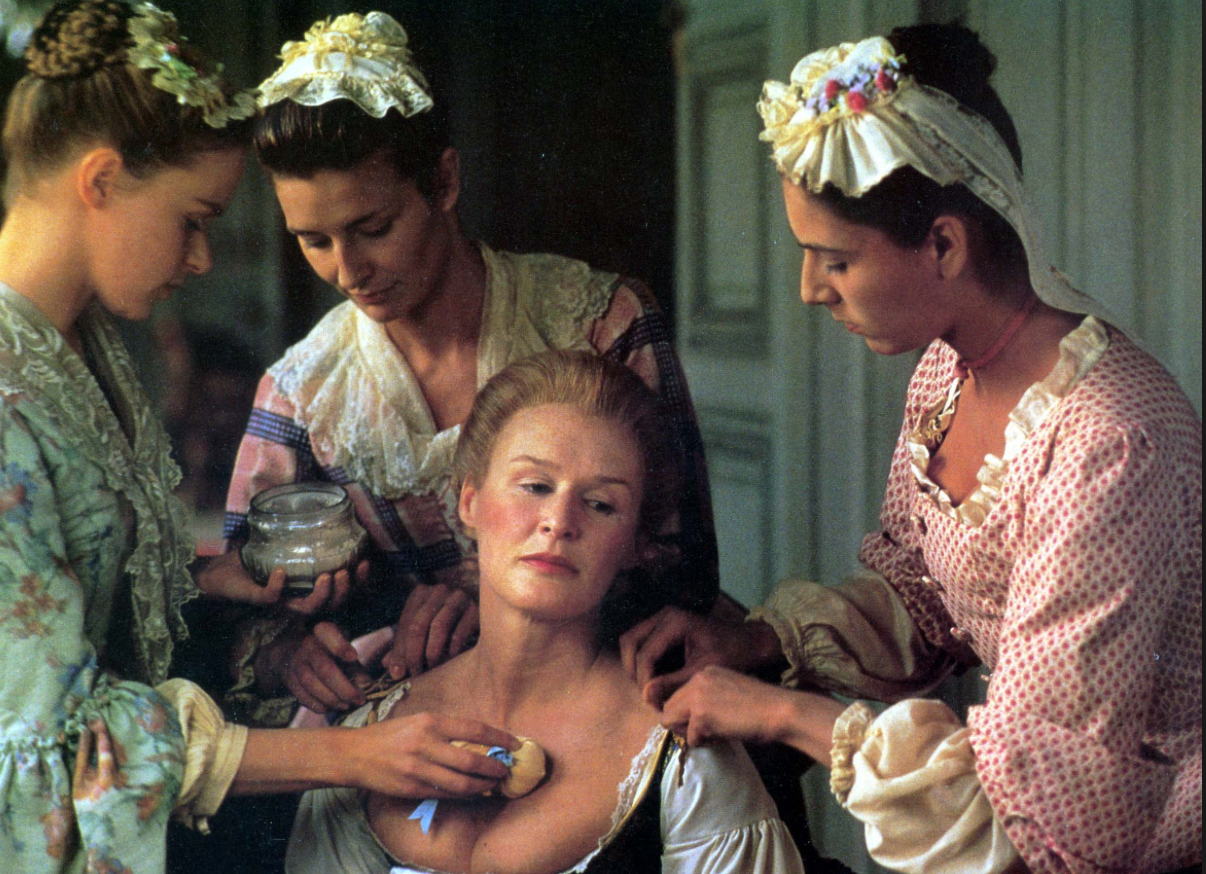

Such lines, stylish as they may be, are just style, not substance. Though this film is molded from a profoundly expository novel (one that’s too seamlessly plaited; there’s a reason it’s mostly read in universities these days), it conveys most in its lush visuals: the powdered skin and wigs, the looking glasses and mirrored doors, the chandeliers and velvet chaises, the pale pink brocades and satin hoop skirts, the pearl chokers and diamond rings, the swelling bosoms and cupid bow lips, the throats thrown back in passion found, passion feigned. All of it amounts to a searing—and eminently pleasurable—comment on the aggressive superficiality of the 1780s and 1980s.

When the chess king and queen’s machinations finally lead everyone asunder—when even such innocents as de Tourvel are led astray by the vanity of their virtue, and Valmont and Merteuil fall on their own swords—Frears is smart enough not to supply much satisfaction. Instead, though he’s heretofore maintained  a snapdragon pace—all clever edits and zinging dialogue (Christopher Hampton’s screenplay is stunning)—he simply puts on a slow fade. The last five minutes, including the inevitable deaths, are virtually wordless. The silence is only broken by boos at the opera, where the Marquise receives a come-uppance I cannot cheer. For, as she then smears the de rigueur white makeup off her raw, red skin, the effect is oddly misogynist, and not only because her skin looks off-puttingly vaginal. It is because her unadorned features loom so hideously. This does not feel like Frears’ misogyny so much as her own—a hatred of the female longings she cannot sate. God is not in the details of this “Dangerous Liaisons” so much as in its decorations.

a snapdragon pace—all clever edits and zinging dialogue (Christopher Hampton’s screenplay is stunning)—he simply puts on a slow fade. The last five minutes, including the inevitable deaths, are virtually wordless. The silence is only broken by boos at the opera, where the Marquise receives a come-uppance I cannot cheer. For, as she then smears the de rigueur white makeup off her raw, red skin, the effect is oddly misogynist, and not only because her skin looks off-puttingly vaginal. It is because her unadorned features loom so hideously. This does not feel like Frears’ misogyny so much as her own—a hatred of the female longings she cannot sate. God is not in the details of this “Dangerous Liaisons” so much as in its decorations.

This was originally published on Signature.