“Julieta,” Pedro Almodovar’s adaptation of the Alice Munro Runaway short stories “Chance,” “Soon,” and “Silence,” was meant to be his English-language debut. Instead, he rechristened the protagonist Julieta and swapped out Vancouver for Madrid, where he contrasted her quiet despair with the bright colors and patterns that are not only that city’s trademark but the Spanish writer/director’s trademark as well.

“Julieta,” Pedro Almodovar’s adaptation of the Alice Munro Runaway short stories “Chance,” “Soon,” and “Silence,” was meant to be his English-language debut. Instead, he rechristened the protagonist Julieta and swapped out Vancouver for Madrid, where he contrasted her quiet despair with the bright colors and patterns that are not only that city’s trademark but the Spanish writer/director’s trademark as well.

If at this point you are thinking, “Gosh, I didn’t know Almodovar had a new movie, let alone that he had adapted Alice Munro,” rest assured you are not the only one. Early festival circuit responses were so lukewarm that its regular theatrical release was buried, and it didn’t even make the Academy Award’s foreign-language short list. Certainly this film has not made any critical top-ten lists except my own. For while I agree with critics who claim this is “not Pedro’s best,” I happen to think his best film (“Todo Sobre Mi Madre”) is one of the best films ever made. “Julieta” is merely one of the best films of 2016.

It also is distinguished by a new restraint that in no way sacrifices the depth of feeling Almodovar always brings to femme-centric fare. From the first shot – a close-up of billowing vermillion drapes and a terra-cotta goddess statue being wrapped by long, tapered fingers boasting a matching red manicure – you know this could be only his work. Yet as the shot widens to include a bleached-out, nearly empty apartment, we also sense a tonal shift – a new economy, perhaps. This does not translate into a pared-down plot, however, for more than almost any working director today, Almodovar loves plot. The storylines of most of his films would fill out three films by most others, and they’re not just operatic, but soap-operatic as well. This also, to my mind, is what codifies them as uniquely feminine – as viewers, we are placed in the traditionally female role of keeping track of many people’s businesses at once.

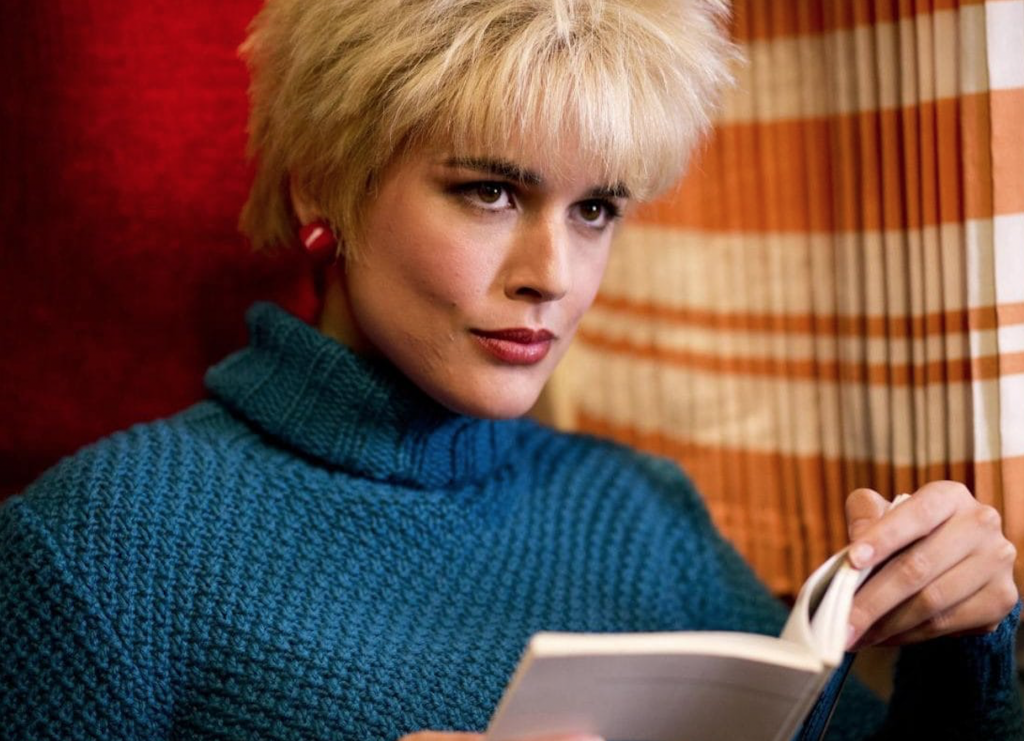

Thus, at the beginning of this film, a middle-aged Julieta (Emma Suarez) is packing to move to Portugal with a boyfriend when she happens upon an old friend of her daughter, Antía. The random encounter changes Julieta’s plans entirely – she reads it as a sign that she should remain at the address where her estranged daughter last saw her – so she unceremoniously dumps her beau and hunkers down. The story then shifts to the 1980s,  when we meet younger Julieta as a bombshell blond classics teacher played by Adriana Ugarte – she looks like the love child of Kim Novac and Almodovar himself – on a fateful train trip that leads to a suicide and drives her into the brawny arms of fisherman Xoan (Daniel Grao), whose wife is mortally ill. The trip ends, Julieta returns to her punkrock schoolmarm existence, but reunites with her lover upon his wife’s death and slips into his seaside life, complete with disproving housekeeper Marian (a gray-haired Rossy de Palma, a far cry from her “Women on the Edge of a Nervous Breakdown” glamour), gorgeous sculptress Eva (Inma Cuesta), and precocious toddler Antía. Hints of infidelities abound – not only in Julieta’s parents’ marriage but in her own – and a confrontation leads to a tragedy that leaves her alone with a now tween-aged daughter.

when we meet younger Julieta as a bombshell blond classics teacher played by Adriana Ugarte – she looks like the love child of Kim Novac and Almodovar himself – on a fateful train trip that leads to a suicide and drives her into the brawny arms of fisherman Xoan (Daniel Grao), whose wife is mortally ill. The trip ends, Julieta returns to her punkrock schoolmarm existence, but reunites with her lover upon his wife’s death and slips into his seaside life, complete with disproving housekeeper Marian (a gray-haired Rossy de Palma, a far cry from her “Women on the Edge of a Nervous Breakdown” glamour), gorgeous sculptress Eva (Inma Cuesta), and precocious toddler Antía. Hints of infidelities abound – not only in Julieta’s parents’ marriage but in her own – and a confrontation leads to a tragedy that leaves her alone with a now tween-aged daughter.

The two relocate to Madrid and, in one striking scene, the transition between the actresses portraying Julieta occurs as Antía dries her grieving mother’s hair, revealing Suarez instead of Ugarte when a towel is removed. It’s a maestro’s trick, for in that one shot we see how Julieta is unknown not only to herself but to her child. (Rarely are parents played by two actors in one film, though offspring often are.) The gap between mother and daughter widens, and soon the younger woman ghosts entirely, joining a spiritual cult and severing all ties to the past.

Alberto Iglesias’s jazz score reverberates with the women’s longings, and the rest of the film’s craft – cinematography, fashion, decor – is characteristically rhapsodic. Almodovar’s palette, always an utter pleasure, has never been more finely hued, and we glide from the peace of aquas, turquoises, and indigos to the crimsons, scarlets, and deep rusts of blood crimes as Julieta confronts how her self-absorption has held her child hostage. The bonds between mothers and daughters have always been grand stories of betrayal – of love found, lost, and sometimes resurrected – and here they  are unpacked with great respect and excruciating authority. Strains of Patricia Highsmith’s no-nonsense noir abound everywhere; it’s no mistake that Julieta’s suitor says he feels like he’s turning into a stalker from one of the author’s novels. But more than any contemporary film or literary reference, Greek tragedy presides – not just in the oceanic roar, in Julieta’s chosen profession, and in Eva’s artistic themes, but in the constant mythologizing of all these characters. The female curse, indeed. In Almodovar’s world, melodrama, not drama, is the most authentic artistic response to the emotional volume of daily life. Coupled with the uncompromising severity of the Ancients and Munro’s powerful restraint, that scale mutates into a new sort of cinematic genre – melodrama, distilled.

are unpacked with great respect and excruciating authority. Strains of Patricia Highsmith’s no-nonsense noir abound everywhere; it’s no mistake that Julieta’s suitor says he feels like he’s turning into a stalker from one of the author’s novels. But more than any contemporary film or literary reference, Greek tragedy presides – not just in the oceanic roar, in Julieta’s chosen profession, and in Eva’s artistic themes, but in the constant mythologizing of all these characters. The female curse, indeed. In Almodovar’s world, melodrama, not drama, is the most authentic artistic response to the emotional volume of daily life. Coupled with the uncompromising severity of the Ancients and Munro’s powerful restraint, that scale mutates into a new sort of cinematic genre – melodrama, distilled.

This was originally published on Signature.