Walking through the galleries of “Mastry,” the two-floor Kerry James Marshall retrospective at Met Breuer, the newest branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I flash on James Baldwin’s quote: “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Walking through the galleries of “Mastry,” the two-floor Kerry James Marshall retrospective at Met Breuer, the newest branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I flash on James Baldwin’s quote: “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Certainly Marshall’s paintings, which I have visited three times in the last month, are profoundly American – proudly, gorgeously, defiantly. In a swoon of silver, brocade, and funeral banners, they embody the beautiful resistance that our country needs most right now – the revolution that has just recommenced. More than that, these paintings ask us to join the movement.

Born in Alabama in 1955, Marshall moved with his family to Los Angeles in 1963 – a classic midcentury migration of African American clans. He has said that his infatuation with Marvel comics began around the same time that he visited the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and certainly both influences are evident in his work. Also evident is the Civil Rights movement, which grew up right along with the artist, often in the same place. He was in Birmingham when four young girls were killed in a bombing of a Baptist church, and was living in L.A.’s Watts section during its 1965 riots. Remaining in that city during his early adulthood, he knew founding members of the Crips gang and studied at the Otis Art Institute, where he opted to become a representational painter querying beauty tropes as well as the eye of the beholder.

Marshall has so much to say about the gaze.

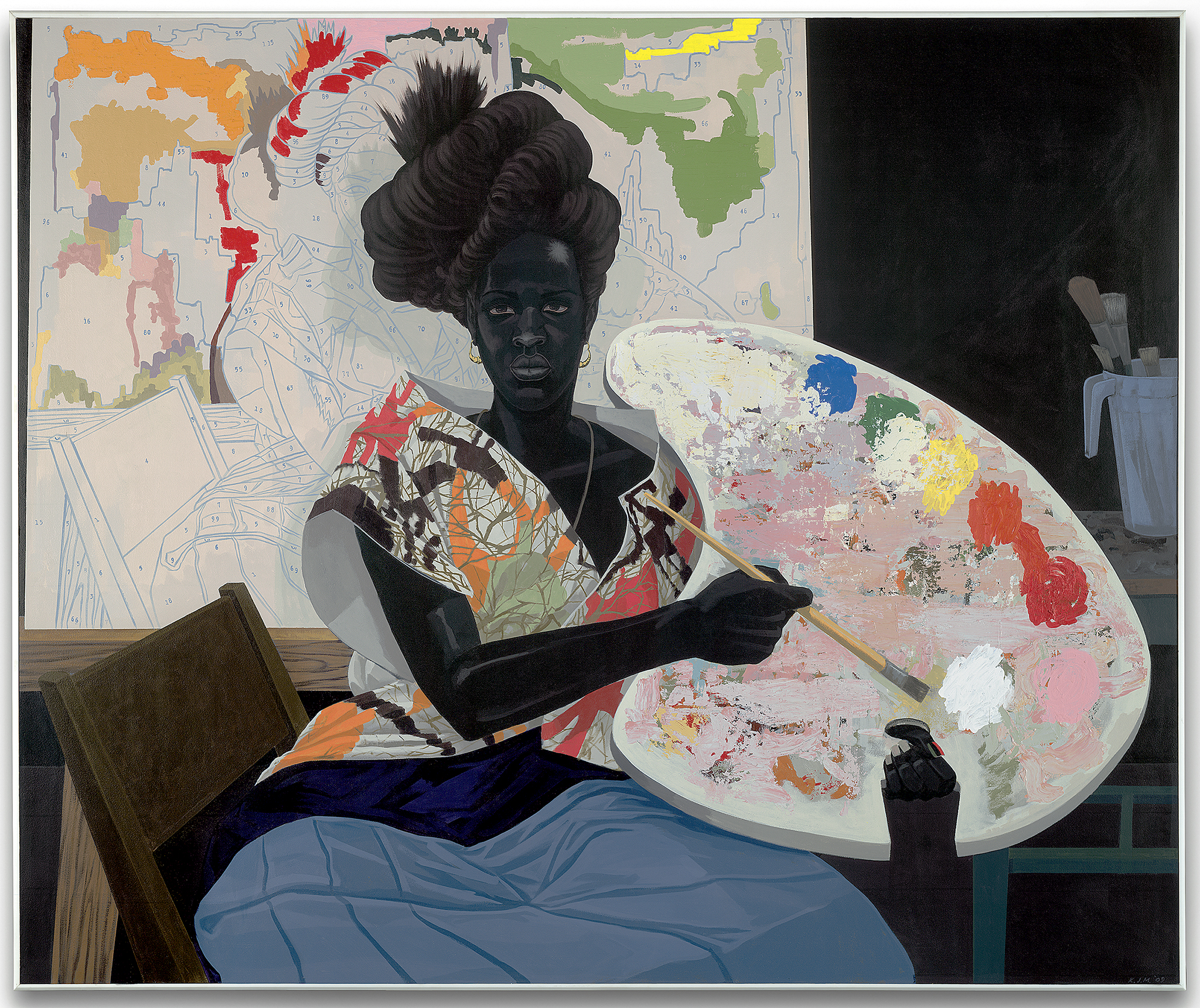

In a series of untitled portraits–nearly all his subjects are black men and women–smock-clad painters turn from partly finished works to view us. Some of their canvases are literally paint-by-numbers – a provocative comment on the strict parameters of the art world – and all are smeared with a rainbow of Marshall’s signature sherbets. The first time I saw this series, I was blown away by  the eyes–un-equivocating, all-seeing, and guarded. I am busy creating art, they are saying. Deal with your feelings about this on your time. Too, their skin is formidably, radically dark – not indigo, not cocoa, but a stunning ebony. Such a dark color is rarely used on Western canvases, and this choice forces us to look closely in order to perceive all the shades and textures embedded within it. Black is beautiful, indeed.

the eyes–un-equivocating, all-seeing, and guarded. I am busy creating art, they are saying. Deal with your feelings about this on your time. Too, their skin is formidably, radically dark – not indigo, not cocoa, but a stunning ebony. Such a dark color is rarely used on Western canvases, and this choice forces us to look closely in order to perceive all the shades and textures embedded within it. Black is beautiful, indeed.

Marshall has said he’d been stuck as an artist until he discovered Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. In a 1986 eponymous painting, he represents the 1952 seminal novel’s most famous quote – “The blackness of blackness is most black” – by very faintly etching a solitary male field worker on a black-on-black canvas. It’s a visual articulation of a vital Ellison theme: that black Americans are rarely seen in their own right by white America. This portrait can be viewed as the Rosetta Stone of this exhibition, one that whispers: If you want to see any of the real story here, you cannot take anything for granted.

Marshall doesn’t just improvise upon cultural conventions; he improves them. He has said: “I wanted to know how to make paintings; but once I came to know that, reconsidering the question of what Art is returns as a critical issue.” Indeed, by inserting black subjects into nearly every Western art canon category – portraiture, history painting, genre scenes, landscape, even abstractions – he is putting these narratives into the larger context of the African diaspora. And diaspora is the right word, for this show (and every painting in it) is not a sprawl so much as a deliberate, ever-expanding diorama – bustling, dazzling, and disorienting, but never disordered. His is an abundance of riches but never an embarrassment.

Hence “Gulf Stream,” an indigo, periwinkle, and glitter-glue reworking of Winslow Homer’s 1899 painting “The Gulfstream” that pulls zero punches in its portrayal of African slaves being shipped to America. Hence the “Vignettes” paintings, which salute French Rococo master Fragonard by casting black romantic love in pink, gold, and Stevie Wonder lyrics lettered in a glamorous cursive. Hence the “Five Gardens” series, which depicts L.A. and Chicago housing projects on enormous, un-stretched canvasses littered with everything from Better Homes and Gardens fonts, “Dick and Jane” tableaus, and Not in My Backyard negativity to bluebirds, boomboxes, and bushes that are decidedly not burning.  Hence “Still Life with Wedding Portrait,” in which a portrait of Harriet Tubman and her husband is being hung by three hands clad in gallerist white gloves and one hand clad in a black leather glove – a nod to the Black Power salute given by Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics. Hence “De Style,” a sly-as-fuck Norman Rockwellian ode to the black beauty shop.

Hence “Still Life with Wedding Portrait,” in which a portrait of Harriet Tubman and her husband is being hung by three hands clad in gallerist white gloves and one hand clad in a black leather glove – a nod to the Black Power salute given by Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics. Hence “De Style,” a sly-as-fuck Norman Rockwellian ode to the black beauty shop.

In a connected gallery curated by Marshall from the Met’s collection, we see works by Henri Matisse, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Pierre Bonnard as well as Horace Pippin and Jacob Lawrence. It’s a ripe array of Odalisques, complete with the wary, cagy gazes of the gazed-upon, and it recalls Marshall’s mentees, painters Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas, who upend the fetishization of black bodies in sweet-and-sour, candy-colored portraits. You can just hear Aretha Franklin demanding: “Who’s zoomin’ who?”

This brings us full circle. It is only fitting that I am trying to do justice to the brilliance of Marshall in the same week that Donald J. Trump is taking office and we are commemorating the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the only twentieth-century leader to earn his own holiday in our country’s calendar. For Marshall’s works – brimming with as many references to Angela Davis, Nat Turner, and the doily-decorousness of front sitting rooms as is to traditional art narratives – remind us that the underbellies of empires are often the prettiest, most powerful parts. His bold beauty – for make no mistake, the main reason hordes of people are trouping to this show is its heart-stopping visual splendor – reminds us that there is no such thing as a black hole in America though there are plenty of black folks. Culture, like nature, abhors a vacuum, and Marshall’s tiger-eyed, celestial paintings comprised of acrylics, oils, wood, leather, lace, comic book lettering, and papier-mâché declare that everything is possible.  In “Mastry,” whose spelling is itself a sly-eyed subversion, a tree doesn’t just grow in Brooklyn. A swan grows in a neighborhood hair salon, and a black artist in the white Western canon.

In “Mastry,” whose spelling is itself a sly-eyed subversion, a tree doesn’t just grow in Brooklyn. A swan grows in a neighborhood hair salon, and a black artist in the white Western canon.

So who am I, a white descendant of Scottish and Ashkanazi Jewish immigrants, to opine on this exhibition? As an American, I have grown on this land tilled with the blood, sweat, and tears of many, many black bodies, and so these paintings investigate my inheritance too–namely, our country’s barbarism and the enormous, often preyed-upon creativity that has flourished in those most betrayed.

What Marshall is doing with exquisite, excruciating grace is asking us to own this legacy. Under his gaze it is not just an American nightmare. It is an American dream as well.

This was originally published at Signature.