The night before Tuesday’s blizzard, I emerged from a critics’ screening into midtown Manhattan. The sky was heavy and violet; the city, already abandoned. The only other people on the street were hurrying along with big bags of laundry and groceries–everything they needed to lay in for the storm. But the film I’d just seen had been much better than I’d anticipated, and I felt the happiness that good work, natural or human-made, has inspired in me since I was a small child; it’s hard to be despondent when beauty in all forms gladdens you this way.

The night before Tuesday’s blizzard, I emerged from a critics’ screening into midtown Manhattan. The sky was heavy and violet; the city, already abandoned. The only other people on the street were hurrying along with big bags of laundry and groceries–everything they needed to lay in for the storm. But the film I’d just seen had been much better than I’d anticipated, and I felt the happiness that good work, natural or human-made, has inspired in me since I was a small child; it’s hard to be despondent when beauty in all forms gladdens you this way.

In that burst of cheer I decided to walk rather than surrender to the weirdness of east 30s public transportation. I bundled up more seriously—double-wrapped my scarf, donned the velvet gloves my mother had sent for Christmas, and took off, knowing it might the last time in a while I’d walk so easily on NYC sidewalks. The air was so cold I could hear little ice crystals forming on my lungs when I breathed; this felt cleansing rather than unsettling. I walked faster, not to hasten my return home so much as to visit with all of the world at once.

I felt love.

I texted love to one of my best friends, hurtling on a train to DC for a gig she was dreading, and she texted it back. I thanked the divine intelligence that had manifested a delivery system for love, and kept bounding along.

By 14th street, though, my nose and cheeks were freezing and I’d begun to worry about how inhospitable the Williamsburg Bridge might be that time of night—all those strangers whipping by in big gusts of wind and bikes and fur hats. Of course I was wearing a big fur hat too—my consolation prize for cold weather—but it has been my experience that you really have to be up to the challenge of the Bridge on winter nights. I flashed on my to-do list for the next day, and suddenly was not.

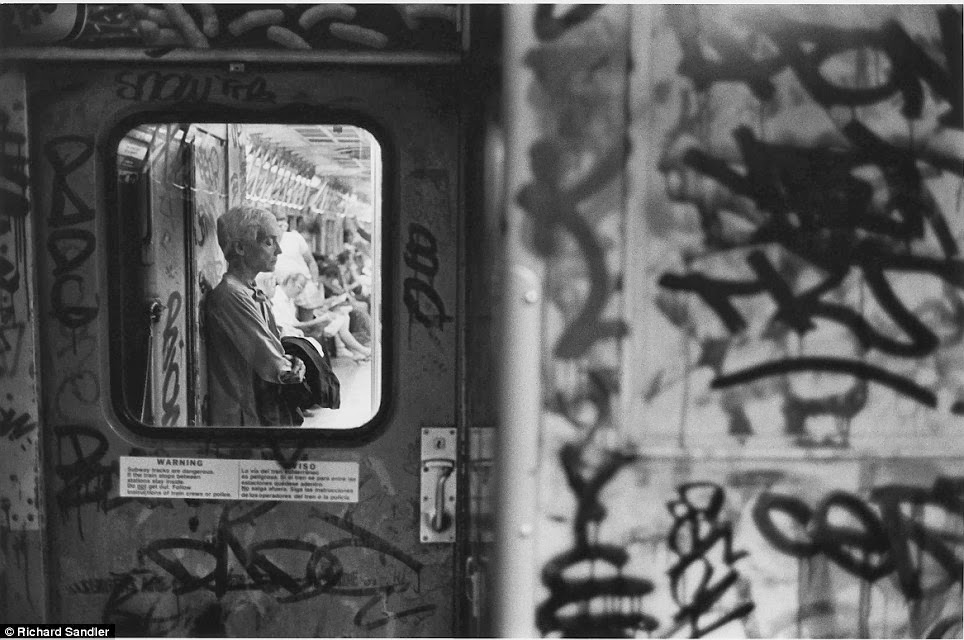

On the L train we all were dwarfed by enormous coats and scarves, less like the adorable kindergarten students New Yorkers usually resemble in wintergear than like Eastern Europeans bracing for a hard night on the shetl. Everyone was clutching their belongings like security blankets.

A woman slammed onto the car. Palms raised, she was vibrating as she walked down the aisle. There’s no other way to phrase it: She was visibly starving. Whether she was a junkie, whether she was fatally ill, whether she’d hurt others, whether she’d made really terrible decisions was less relevant than the palpable fact that, as she stood before us, her body had not absorbed significant nutrition for a very long time. Her thighs were as as thick as her wrists; her eyes loomed like yellow saucers from the skeleton of her face. Her head, uncovered, revealed the fuzz of an unmothered duckling.

We were hurtling under the river then and the darkness of the tunnel swelled all around us. For a second the lights went out too, and in the blackness of the train I could sense her human need pulsing, saw that somehow it still shone. When the lights came back on, I pulled out all the cash in my wallet—it wasn’t much, but it was hers—and most everyone else did the same. More than a few took groceries out of their bags and held them out to her with calm eyes and no words. She accepted it all impassively. I sensed no hostility or ingratitude, only the economy of a body already shutting down.

I have lived in New York City for 24 years and have never experienced anything like that exchange though I’ve witnessed many other tender mercies. Would she live out the year? Selfishly I hoped she would—and how else could I hope this but selfishly? I’d never met her before, hadn’t spoken with her, would likely never see her again. All I knew was her light, and it was glorious , so bright that it had roused a bevy of New Yorkers. She was impossible to miss: a cousin radiant in the deepest of crisis.

, so bright that it had roused a bevy of New Yorkers. She was impossible to miss: a cousin radiant in the deepest of crisis.

In my heart of hearts I know we all are cousins–all children of a loving universe. I know this because of the many times I have been guided and protected by unseen channels. I know this because I knew to pray before I knew there was a divine Mother. And just as I know this, I know that each of us who’d been in that woman’s presence felt more compassion for others living without protection. As I walked off the train, I saw people from my car handing food and money to those settled onto the platform for the storm to come. I had nothing left to give but my love; this I beamed freely and joyously. As I write I am beaming it still.