Friends from Boston sometimes visit me in my hermitage, as Beztie calls it. Rachel made time between a trip to Ireland and adopting two Corgi puppies to spend a Sunday with Grace and me. We had a very Lisa and Rachel visit, which is to say we bought everything but the wallhangings at a French bakery, feasted beneath a lady-like umbrella, and made wishes at a bay beach. Like a good fairy godmother, she brought the big cup and the bigger sweater I’d been craving, and we skipped our grown-up plans in Provincetown to tell each other secrets not suitable for Facetime. My overfamiliar presided over us on the screened-in porch.

Friends from Boston sometimes visit me in my hermitage, as Beztie calls it. Rachel made time between a trip to Ireland and adopting two Corgi puppies to spend a Sunday with Grace and me. We had a very Lisa and Rachel visit, which is to say we bought everything but the wallhangings at a French bakery, feasted beneath a lady-like umbrella, and made wishes at a bay beach. Like a good fairy godmother, she brought the big cup and the bigger sweater I’d been craving, and we skipped our grown-up plans in Provincetown to tell each other secrets not suitable for Facetime. My overfamiliar presided over us on the screened-in porch.

Melina, the friend with whom I’ve adventuressed since the late 1970s, took a ferry over and we visited that bay beach, too. As the sun set, we slipped out of our sand-filled suits and into the still water, sleek as sea lions. It was my first time skinny-dipping in decades, and the ladies enjoying their wine on the sand were horrified. The purification was necessary after our Ballston Beach escapade, though.

Since I’ve been on the Outer Cape, Ballson has been my home away from home. Outside of the desert, its endless white sands and eastern orientation make it the best place I’ve ever watched the sunrise. Seals often pop out of the surf to keep me company, and gulls circle with a solemnity proper for the occasion.

Melina and I had planned a woodsy walk, but it was so hot for late September that we opted for what I learned was her favorite beach as well. We brought books, blankets, snacks. When we arrived, though, the sea sang such a sweet song that we headed straight into the water.

The tide was terrifyingly strong that day, the waves rising three or four times as high as our heads. We went in anyway. After about a minute, I was pretty sure I would die. I still think it was possible. There were no life guards on the beach, only a few locals watching us as dispassionately as they’d watch a horse race on which they hadn’t bet.

A wave toppled Mel and me, and when the the tide started pulling us out, I dove low and swam as hard as I could, anchoring my feet in the sand as soon as they touched ground.

“That’s it for you?” Melina called when I came up for air, and I waved, feigning a casualness I did not feel. My heart was crashing louder in my chest than the surf on the shore. She bopped for a while, and, shivering in a towel, I watched with the cold anxiety Grace radiates when watching me take a bath. Water is so dangerous, I can hear permakitten thinking.

Eventually Melina emerged, covered in seaweed and sand like a goddess of the sea, and we began walking down the beach. The tide was rising rapidly and I asked if our unattended things would be okay. “They’re fine,” Melina said, but the city girl in me snatched my keys before we took off. Hot and cold fronts fought it out as we made our way: one spot a steam-room; the next chilly enough for a sweatshirt. “This is awesome,” Melina said, hopping between them as when we were younger than her daughters, my goddaughters. The sky and sea met at the horizon, and everything smoothed into shades of blue and bone. The light was beautiful and treacherous.

I clutched my keys tighter.

As so often happens when I am overwhelmed, my phone went dead then. No distancing, I thought, and smiled. We walked on and a pair of seals kept pace, gliding right past the sea’s first crest and smiling whenever we said hi. We climbed into the dunes, Melina showing me the path I’d been reading about but had not been able to find on my own. “We came here once in the winter,” she said, and I remembered what had not seemed familiar before. Though I am ten days older than her, I felt like a dumb, book-smart little sister, which is often our dynamic outside of cities.

As so often happens when I am overwhelmed, my phone went dead then. No distancing, I thought, and smiled. We walked on and a pair of seals kept pace, gliding right past the sea’s first crest and smiling whenever we said hi. We climbed into the dunes, Melina showing me the path I’d been reading about but had not been able to find on my own. “We came here once in the winter,” she said, and I remembered what had not seemed familiar before. Though I am ten days older than her, I felt like a dumb, book-smart little sister, which is often our dynamic outside of cities.

The view was gorgeous from the dunes, and we walked through the high yellow grass, the sky somehow bluer. I confessed that walking by myself on the trails felt like riding a rollercoaster might for someone else. “Technically I know the path is clearly marked and I will find my way,” I said. “But if I’m not walking on a grid, nothing’s for certain. I’m always thinking that no one knows I’m gone, so no one will come looking.”

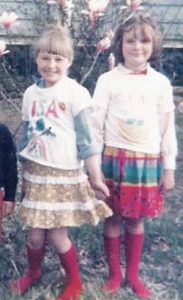

Melina nodded, and pointed to a sand pit into which I was about to fall. We’ve been friends since elementary school, when our bedrooms were separated by three backyards and one street, and we’ve swapped the alpha role back and forth the whole time. I joke that, combined, we’d make the ultimate superhero.

When we descended to the beach, the tide had risen almost to the dunes themselves. We looked at each other and without a word starting running toward our bags, a mile down the beach. My heart thumped harder, and she sprinted in front of me–the red of her bathing suit blurring in the distance with the red of the blanket I’d found on a sola road trip. Another scary adventure, come to think of it.

other and without a word starting running toward our bags, a mile down the beach. My heart thumped harder, and she sprinted in front of me–the red of her bathing suit blurring in the distance with the red of the blanket I’d found on a sola road trip. Another scary adventure, come to think of it.

As I jogged behind her, I thought about what was in the bag that likely had floated to sea. My wallet was in my car, my keys were in my fist. I’d lose my iPhone and a notebook, a pair of sunglasses of which I’m especially fond.

“In other words, nada,” I said aloud and slowed to a walk again. Above, the heat shimmered wide and ancient; ahead, my oldest friend merged with the horizon; at right bobbed the same seals who’d kept us company all afternoon. Nothing else mattered.