After I’d been living in my current apartment for six years, a cute couple moved in across the hall. I was going through a phase in which I detested cute couples, and I’d never been a fan of neighbors. Part of why I’d moved to New York in the first place was to claim the voluptuous anonymity the city promised. My clan had never been big on boundaries and on top of that there’d always been Old Lady MacNamara. Hanging over the fence between our two houses, she’d spent her days passing judgment on my half-Jewish family’s goings-on as she smoked the cigarettes that eventually killed her.

After I’d been living in my current apartment for six years, a cute couple moved in across the hall. I was going through a phase in which I detested cute couples, and I’d never been a fan of neighbors. Part of why I’d moved to New York in the first place was to claim the voluptuous anonymity the city promised. My clan had never been big on boundaries and on top of that there’d always been Old Lady MacNamara. Hanging over the fence between our two houses, she’d spent her days passing judgment on my half-Jewish family’s goings-on as she smoked the cigarettes that eventually killed her.

I defined a good neighbor the same way I defined good weather: an entity that never made its presence known.

But T and G were different. The day they moved in, I was scrubbing my apartment with the doors and windows flung wide open, blasting the air with Aretha Franklin’s Soul 69 and hippie cleansers. They grinned at me over the boxes they were toting but made no idle chitchat. A few days later, T came by looking for a needle. While I fetched her one, she eyed the coathook precariously hanging from my wall. “I’m bad at boy things,” I told her. “And my boyfriend and I just broke up.”

She didn’t say anything, but returned a day later with a toolbox and reattached the hook. No processing first or “I’ll do it later, baby.” Just a girl with a drill. I began to grasp the advantage of good neighbors over mediocre boyfriends.

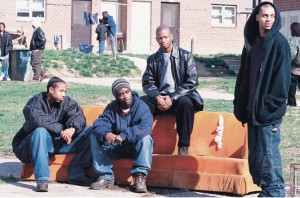

Slowly we all became friends. I dropped off copies of the lurid gossip magazine where I was working and leftovers from my Sunday dinners. They helped me hang all my pictures and brought over leftovers as well. All of us, it turned out, liked to cook, though T didn’t love meat as much as G and I did, and I tended to cook with more butter and salt than both of them put together. As the nights grew colder and longer, we’d sip wine and make meals together. Afterward, we’d watch The Wire, which they’d never seen and at whose altar I worshipped in an annual ritual of strict sequence and even stricter silence. (First rule of The Wire: You are not smarter than The Wire so you do not interrupt The Wire.) One night, as we noiselessly took in back-to-back episodes of Season 2 on their tweedy couch, I realized I’d come to love my neighbors.

T and I discovered we had been born two hours apart on the same day and the same year—a fact that both fascinated us and cemented our sense that our “across the hall” connection was providential. Our similarities and differences suddenly shimmered into high relief: Born to Ukrainian immigrants, she was a respected visual artist who’d shown in Chelsea galleries and European museums. Smaller than me, she was beautiful with olive skin and a sheet of long dark hair that flowed down her back, as well as the prominent bone structure that I shared (a Capricorn staple). I was bustier and blowsier, and the twisted wit I’d inherited from my Jewish-Scottish clan contrasted sharply with her guileless manner. I was better with words and music; she, hands and eyes. But we both enjoyed physical humor and general silliness despite having weathered more than our fair share of hard times. And we both were deeply focused upon, even distracted by, how to make the work we felt called upon to do. How To Be of Use, to quote Marge Piercy. One day while walking back from the grocery store T confided that she was sure that, together, we’d comprise the world’s most perfect superhero. I was pleased by the prospect of our costume as well as the sense of belonging her theory offered us both. That our bond had appeared seemingly out of nowhere felt providential indeed.

T and I discovered we had been born two hours apart on the same day and the same year—a fact that both fascinated us and cemented our sense that our “across the hall” connection was providential. Our similarities and differences suddenly shimmered into high relief: Born to Ukrainian immigrants, she was a respected visual artist who’d shown in Chelsea galleries and European museums. Smaller than me, she was beautiful with olive skin and a sheet of long dark hair that flowed down her back, as well as the prominent bone structure that I shared (a Capricorn staple). I was bustier and blowsier, and the twisted wit I’d inherited from my Jewish-Scottish clan contrasted sharply with her guileless manner. I was better with words and music; she, hands and eyes. But we both enjoyed physical humor and general silliness despite having weathered more than our fair share of hard times. And we both were deeply focused upon, even distracted by, how to make the work we felt called upon to do. How To Be of Use, to quote Marge Piercy. One day while walking back from the grocery store T confided that she was sure that, together, we’d comprise the world’s most perfect superhero. I was pleased by the prospect of our costume as well as the sense of belonging her theory offered us both. That our bond had appeared seemingly out of nowhere felt providential indeed.

Her relationship with G, another visual artist who was a few years younger than us, intrigued me. He’d also grown up rough, though he was mum on the details. Mostly he smiled a lot and expended his residual anger in an amazingly dedicated martial arts practice. Together the couple seemed grounded in a daily gentleness that I’d never experienced with a male partner. And it was a gentleness that seemed to flow across the hall, where even my two cats, whom I’d rescued from a shelter, maintained an ethic of tough love. Rather than gritting my teeth or banging on the wall when my neighbors’ music floated into my apartment, I learned to ask them quietly to turn it down—unless G was blasting Fela, whom I dug as well. In the same vein T taught me how to close rather than slam a door. (I complete all physical tasks with great gusto and limited grace unless specifically instructed otherwise.)

All of our lives got harder. After the housing bubble burst and the stock market crashed that fall, arts grants grew harder to obtain and gallery business was not exactly booming. T was forced to pick up freelance design work, but even the gigs she loathed proved increasingly difficult to come by. G started a full-time job he wasn’t sure he wanted other than to cover their bills. My gossip magazine job, which before I’d only jokingly referred to as reprehensible, grew more onerous. I started to feel trapped by how few well-paying media jobs were still in existence, especially since my boss was my now ex-boyfriend, who cooed all day long into the phone with his new girlfriend. Worse, my cat Ruby was diagnosed with lung cancer and began her not-so-slow decline. I came home from work each evening to clean her pools of vomit while Max, my other cat, mewed anxiously. Grimly I began researching the correct time to euthanize a fatally ill animal, though I was scarcely able to absorb this was the only way I could help the kitten I’d rescued 15 years before.

The reality of all of our circumstances started to grind us down. We slowed down our Wire consumption as it felt too close to home. Nerves wore thin and I grew sadder and quieter. For the first time snatches of arguments drifted through our shared wall. I spent more time alone, unwilling to impose my blanket of misery on anyone else, less capable of navigating my neighbors’ suddenly charged dynamics. One day I ran into them in the hall and they confessed they’d soon be moving to a cheaper neighborhood so T could continue to afford an art studio. I was so stricken I could barely respond.

Then one night we all got snowed in. A blizzard began early in the day, the fourth blizzard of that brutal winter, and it just didn’t let up. By nightfall the neighborhood took on the reverent, glittering hush that can only be achieved in Brooklyn by snow. But the beauty was wasted on me. The despair I’d been barely holding at bay, the deep grief and abject loneliness I so rarely acknowledged even to myself, took root. The severity of the storm had forced restaurants and stores to close, and my larder was uncharacteristically bare. The uneven heating in my apartment couldn’t hold its own against the winds howling right outside. The loveliness of the weather hurt because my former sweetheart was enjoying it with another. And the cats, on standby to dispense their usual massive doses of love despite their own worries, hurt my heart as well since I now recognized my time with them was finite. By 7 pm I was already stationed at the window in my flannels and a woolen hat and scarf, hungrily viewing the tableau of white-laced trees and 20somethings building snowmen right outside my unwashed window. I, who’d been doggedly improvising alternatives to disappointment since I first could read and write, felt helplessly bleak.

Then one night we all got snowed in. A blizzard began early in the day, the fourth blizzard of that brutal winter, and it just didn’t let up. By nightfall the neighborhood took on the reverent, glittering hush that can only be achieved in Brooklyn by snow. But the beauty was wasted on me. The despair I’d been barely holding at bay, the deep grief and abject loneliness I so rarely acknowledged even to myself, took root. The severity of the storm had forced restaurants and stores to close, and my larder was uncharacteristically bare. The uneven heating in my apartment couldn’t hold its own against the winds howling right outside. The loveliness of the weather hurt because my former sweetheart was enjoying it with another. And the cats, on standby to dispense their usual massive doses of love despite their own worries, hurt my heart as well since I now recognized my time with them was finite. By 7 pm I was already stationed at the window in my flannels and a woolen hat and scarf, hungrily viewing the tableau of white-laced trees and 20somethings building snowmen right outside my unwashed window. I, who’d been doggedly improvising alternatives to disappointment since I first could read and write, felt helplessly bleak.

I may have remained at that window forever, frozen inside and out, had G not knocked on my door. When I opened it, he looked at my getup for a long second. “We’re cooking up a whole mess of beans,” he said. “You should come over.”

I breathed in, about to say no, when T danced behind him, irresistibly decked out in multicolored striped socks and a mumu. “Come over, Liser!” she said. I pulled on a pair of striped socks of my own.

In their brightly lit kitchen, Manu Chao was singing about three little monkeys and all four stove burners were aflame, steaming the windows and beading our foreheads. It was like a tiny, cheerily soundtracked urban sweat lodge. T handed me a glass of wine and a chef’s knife. “Drink! Chop!” Dutifully I sat at their round wooden table, laid out with tablecloths, plates, cutlery and napkins in bold pastels, and began to unpeel a head of garlic as the two whirled around me in a dervish of activity. Periodically they handed me something else to chop as they chattered about the snow, the cold, our friends in common, the recent inauguration. In no time, the table filled with warmed tortillas, a roasted chicken rubbed with chipotle and sea salt, chopped herbs, bowls of crema and rice, hot sauce, greens, limes, avocado and, as the piece de resistance, a heaping pot of garlicky, spicy beans.

We regarded the products of our labor. “Beans are so good,” T said as we began to dig in. I agreed: “They’re healthy, they’re cheap, they’re primitive, they’re modern. And the dried ones are so pretty.” We ate some more in the Quaker-meeting silence we normally reserved for The Wire. Then G said, “Every culture eats beans” and I burst into tears. In that small kitchen in our rickety building at a corner of a neighborhood and a city and three lives that had already changed so much and were about to change a great deal more, it was a relief to cry just then. I knew, at least that night, I’d be fed.

The Beans

This is T and G’s recipe, written in their endearing prose, with a few modifications. It is simple, because beans don’t need to be super-fancy to cure what ails you, but I do recommend serving them up with such extras as lime, hot sauce, crema, chopped cilantro and avocado, and extra-coarse sea salt sprinkled atop. And of course: rice is always nice.

Ingredients:

(Consider these rough measurements.)

1 pound dried pinto or black beans

4-10 cloves of garlic

1 ham hock, optional

2-3 minced jalapeno or serrano peppers

1-2 teaspoons of cumin seeds

2-3 tablespoons of olive oil (for sauteeing garlic, peppers, and cumin)

Good vinegar (red wine, balsamic, sherry, even white, whatever’s on hand that is of good quality. Just make sure it wouldn’t best be used as cleaning fluid or varnish.)

Sea salt to taste

Preparation:

Soak beans in fridge in plenty of water overnight. Boil’em ups the next day–with ham hock. if you like. You can start early and turn off when tender or start 2-3 hours before dinner. Just be sure to turn off when tender to avoid overcooking. (You can add salt to the beans once they’re already boiling.)

In a pan, saute minced garlic, sliced peppers (careful of those seeds, man!), and cumin. Add to beans before the garlic browns. Cook for a little more in order to fuse flavors. Add a good dollop of vinegar for depth of flavor.

Check for salt and seasonings. Serve!