My friend Hopie has an acronym that I love: “TMTM.” It stands for “The More, The Merrier,” and back in our twenties we used it when assembling invitation lists for club outings and dinner parties. These days, I’ve found a different application for the term: to nip female competition in the bud. Which woman is prettiest, funniest, smartest? Why choose? TMTM!

My friend Hopie has an acronym that I love: “TMTM.” It stands for “The More, The Merrier,” and back in our twenties we used it when assembling invitation lists for club outings and dinner parties. These days, I’ve found a different application for the term: to nip female competition in the bud. Which woman is prettiest, funniest, smartest? Why choose? TMTM!

I mention this because, with the season premieres last week of both “Broad City” and “Girls,” comparisons between the two shows are flying fast and furious. In a way, it’s inevitable. Both are half-hour TV comedies about young women stumbling through New York City. But strike the “women” from that premise, and we’ve got the description of many of TV’s most successful sitcoms over the last fifty years, from “Friends,” “Seinfeld,” and “Will and Grace” to “Taxi” and even “I Love Lucy.” So rather than pitting them against each other, “Broad City” and Girls” deserve to be lauded for their individual merits. An either/or binary is a scarcity model that assumes only a limited number of females should be allowed to shine. And if there’s one thing these two shows do have in common, it’s that both deserve their moment in the sun.

“Girls,” which commenced its fourth season on January 11 with one of its best episodes yet, is more of a collection of interconnected art-house shorts than a traditional TV show. Its humor is often so obscure that it recalls the old joke: Question: How many surrealists does it take to screw in a light bulb? Answer: Fish. A true writer’s show (star and showrunner Lena Dunham has written many episodes as well as her own bestselling memoir), it is all about craftsmanship and how to fit into larger bohemian artistic traditions, especially in the hash-tagged wilderness of contemporary life. Though initially criticized for nepotism, the fact that “Girls” stars four women who hail from media- and arts-industry families actually dovetails nicely with its unflagging enthusiasm for avant-garde forebears. This series looks backward at least as much as it looks forward, and it does so with such a gentle subversion that most mistakenly conflate the thuddingly solipsistic Hannah with Dunham, the old-soul, neon-clad mastermind.

“Girls,” which commenced its fourth season on January 11 with one of its best episodes yet, is more of a collection of interconnected art-house shorts than a traditional TV show. Its humor is often so obscure that it recalls the old joke: Question: How many surrealists does it take to screw in a light bulb? Answer: Fish. A true writer’s show (star and showrunner Lena Dunham has written many episodes as well as her own bestselling memoir), it is all about craftsmanship and how to fit into larger bohemian artistic traditions, especially in the hash-tagged wilderness of contemporary life. Though initially criticized for nepotism, the fact that “Girls” stars four women who hail from media- and arts-industry families actually dovetails nicely with its unflagging enthusiasm for avant-garde forebears. This series looks backward at least as much as it looks forward, and it does so with such a gentle subversion that most mistakenly conflate the thuddingly solipsistic Hannah with Dunham, the old-soul, neon-clad mastermind.

In interviews, Dunham has expressed an appreciation for 1979’s “Girlfriends,” a mostly forgotten cinematic valentine to female friendship that smacks as much of Cassavetes as of Woody Allen, and shades of that atonal masterpiece drift through nearly every episode of her show. Older actors rounding out this cast comprise a who’s-who of under-utilized comedy stalwarts: Louise Lasser as the wheelchair-bound artist boss of Jessa (Jemima Kirke), Rita Wilson as the Gypsy Rose mama of wannabe folk singer Marnie (Allison Williams), Peter Scolari and Becky Ann Baker as the parents of Hannah (Dunham), Aussie wag Ben Mendelsohn as Jessa’s dad. But “Girls” never leans too heavily on clever casting; instead, all those surprise cameos jibe with the angular, jagged pacing, cinematography, artistic design, editing, and scripts. Just when we think we grasp the balance between these girls’ narcissism and compassion, the rug is pulled out from under us. If there’s one thing we can count on in this series, it’s that it will deliver as many unsettling revelations about the bonds of family, friendship, and romance as it will flat-out laughs.

Just in this season’s premiere episode, in which Hannah bids her Brooklyn community goodbye as she heads to the Midwest for a creative writing MFA, a group of regular-sized women are described as “lazy bulimics”; Hannah wears a glazed smile as her disappointed-actor boyfriend Adam (Adam Driver, yum) hijacks a family dinner; Marnie (normally anal only in the Freudian sense) receives analinguis; Jessa behaves “just mean enough” at Hannah’s goodbye brunch; and Hannah and Marnie fall into a silent, sad hug as they zip her suitcase. It’s all here in this show: the messy, gorgeous gestalt of being young in a world that isn’t clamoring for our contribution.

Just in this season’s premiere episode, in which Hannah bids her Brooklyn community goodbye as she heads to the Midwest for a creative writing MFA, a group of regular-sized women are described as “lazy bulimics”; Hannah wears a glazed smile as her disappointed-actor boyfriend Adam (Adam Driver, yum) hijacks a family dinner; Marnie (normally anal only in the Freudian sense) receives analinguis; Jessa behaves “just mean enough” at Hannah’s goodbye brunch; and Hannah and Marnie fall into a silent, sad hug as they zip her suitcase. It’s all here in this show: the messy, gorgeous gestalt of being young in a world that isn’t clamoring for our contribution.

“Broad City” is a lighter touch, one that lives up to its own name with jazz hands and a waggle of the eyebrow (and the bum). Starring real-life besties and showrunners Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson, the Comedy Central series retains the appealing shagginess of the YouTube webisodes from which it evolved. The duo, who have said in interviews that they are playing younger versions of themselves, bop through dead-end jobs, crappy apartments, stoned reveries, subway rides, and mostly short-lived romantic entanglements with an optimism that isn’t entirely misinformed. Just when we think we have them pigeonholed, they turn everything upside down – sometimes literally. (Glazer and Jacobson are quite the physical comedians.)

Typically, Abbi, a custodian for a gratingly hip gym, is more restrained than Id-incarnate Ilana, but occasionally the former roars to the forefront as in “The Last Supper,” in which she’s jacked with an Epi-pen meant for an allergy-stricken Ilana, or in “Fattest Asses,” in which she goes renegade at a swanky party. In general, the pair are most focused on their own relationship, which is platonic even if Ilana pants over Abbi’s “ass of an angel” and is always idly trying to cajole her into bed. One of the long-running jokes of the series is the practically nonexistent boundaries between the two – and between most people in their twenties. The pair scrutinize each other’s sex lives, outfits, meals, weed supply, and finances over FaceTime on the rare occasions that they’re not in the same room. In one scene they actually talk on FaceTime while Ilana is having sex with Lincoln (Hannibal Buress), her sort-of beau who, as a dentist, is the series’ most stable character. (As an African American, he also topples long-held stereotypes about relationships between black men and white women.) Matt Bevers (John Gemberling), the boyfriend of Abbi’s mysteriously absent roommate, masturbates on the living room couch to Abbi’s DVR’d episodes of “The Good Wife” no matter how many times she questions his presence in her apartment.

Jubilantly loose-limbed, Ilana isn’t above sleeping with a man for washing machine access but she also won’t brook any catcalling nonsense as she dances down the street. Neither of these ladies will: Their feminism – like their youth, their physical appearance, and their improvisational wit – is unchecked, un-streamlined, uncompromising, and awesome. Buzzing with vaudevillian bravado and hip hop rhythms, “Broad City” lives in the moment so completely that it doesn’t bother to look where it’s going. For a half hour at least, this gives us permission to do the same.

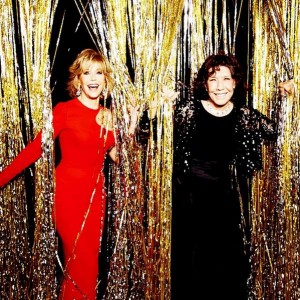

At this year’s Golden Globes, Lily Tomlin and Jane Fonda cracked that “finally we can put to rest that negative stereotype that men just aren’t funny.” Though she was playing on the old saw I won’t even repeat here, the truth is that, for the first time in a while, women in comedies aren’t just eye-rolling regulators and the objects of undeserving men. They’re the wild-and-crazy pratfallers as well as the sly-eyed surrealists. Rather than haggling over who’s better, we should salute each of their freak flags as they fly. TMTM!

This essay was originally published in Word and Film.