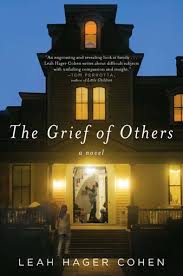

Though it’s rarely acknowledged, dynamics between authors and the directors who have adapted their books can be awkward, to say the least. This awkwardness was very much not in evidence at a post-screening discussion of “The Grief of Others,” about a family grappling with the death of their infant, that I moderated between author Leah Hager Cohen and director/screenwriter Patrick Wang. It’s safe to say that it was a genuine love-in, one that taught everyone present something about filmmaking, writing, and even – at the risk of sounding lofty – the human condition.

Though it’s rarely acknowledged, dynamics between authors and the directors who have adapted their books can be awkward, to say the least. This awkwardness was very much not in evidence at a post-screening discussion of “The Grief of Others,” about a family grappling with the death of their infant, that I moderated between author Leah Hager Cohen and director/screenwriter Patrick Wang. It’s safe to say that it was a genuine love-in, one that taught everyone present something about filmmaking, writing, and even – at the risk of sounding lofty – the human condition.

It helped that Wang and Cohen were friends long before they embarked on this collaboration. “I was a huge fan of Patrick as an artist, so it was easy to trust the sensibilities and ethics he’d bring to the project,” explained Cohen, who speaks in unusually sweet, precise cadences. “I was like, ‘I made this book, and now Patrick will make this film.’ It felt wonderful to let go of ownership.”

Wang beamed, and added in his soft voice, “I learned so much from this book, which is why I wanted to adapt it. It is about the universality of grief, about how it separates us even as it connects us, which is something Leah and I had a lot of conversations about before I went away to write the screenplay by myself.”

About her inspiration for this novel, Cohen spoke frankly of her struggles in the aftermath of a miscarriage. “My mother gave me the gift of showing me how my isolation was compounding my grief, and of speaking to me about how I was in community even if I couldn’t feel it; of how, even if I wasn’t face to face with other women experiencing this pain, they were around the globe and in my ancestral line. In my writing, I started with this fact.”

She admitted that she had worried many aspects of her book would not be very cinematic. “Patrick changed those ‘I worries’ to ‘I wonders,’ and came up with visual solutions,” she said, referring to one scene in which the extended backstory of a character’s sexual ambivalence is represented by a moment in which a woman morphs into a man and then back into a woman again.

About his admittedly ambiguous “visual solutions,” Wang added, “In life there are so many instances in which we only have scraps of information and yet we make sense out of what we’re presented. I have faith in audiences’ ability to piece truths together if we give them enough clues. It’s actually very literary because this process is almost the exact definition of reading. You’re filling in the blanks with your imagination. And, let’s face it: There is never just one interpretation anyway.” He went on to explain this is why he shoots significantly less “coverage” – various shots of the same scene – than most directors. “Actors have more freedom when they don’t have to keep replaying and replaying for all that coverage. And most scenes have a “sweet spot,” an angle from which perfect information flows, which will develop the story. If you stay with that first shot you chose, you learn from it.”

Rachel Dratch, best known for such “Saturday Night Live” characters as “Debbie Downer,” has a small but key role in this film as Madeleine, a professor who provides unexpected insights. She is wonderful in what for her is an unusual dramatic turn. Wang explained, “She has a great agent who saw this role and thought of her. This character is at first a figure to laugh at. She is pretentious, single, grasping. But then you see beyond that.”

Cohen said, “When I first wrote the character of Madeleine, I was very selfish. I was having fun sending her up in a two-dimensional way and didn’t expect to see her in the novel again. But I don’t outline my books and late in the process Madeleine surprised me by showing up again in a pivotal crisis moment. She comes through with all these other dimensions and levels of humanity and I realized  that my own limited thinking had led me to underwrite this unmarried woman, to sell her out. I grew as a person as well as a novelist when she reappeared and I had to explore her complexity. It was my humbling as an author.”

that my own limited thinking had led me to underwrite this unmarried woman, to sell her out. I grew as a person as well as a novelist when she reappeared and I had to explore her complexity. It was my humbling as an author.”

When asked if the process of adapting The Grief of Others to screen had changed her as an author, Cohen said, “This experience has taught me that I take a lot of care to not unsettle readers, and that this perhaps forecloses on their freedom to wonder and imagine. Working with Patrick has impacted me to not over-explain so much in the new novel I’m writing. The making of this film has taught me to have more faith in my audience.”

This was originally published in Word and Film.