This is the second installment of my tale about Ute. You can find the first here.

This is the second installment of my tale about Ute. You can find the first here.

By 1998, I was finally on my own after a decade of living off men after leaving my parents’ house—frying pan, meet fire. I was living alone in a ridiculously affordable Prospect Heights floor-through with a backyard, rotating through a series of lovers, free-lancing as a copy editor, working out at least once a day, and writing the occasional magazine article about holistic health. Back then you could make grownup money as a journalist but working full-time in a magazine would’ve cramped my yoga girl lifestyle so I resigned myself to pitching articles that would earn me coin while I learned about something that already interested me. Getting paid a buck a word to take a vacation where anorexic me could manage the food always felt like a good call.

The magazines I wrote for were mostly the kind of rich-people vanity projects that were long dead by the time everything crashed in 2008, and their editors were usually inexpert enough that they were desperate for my “boho girl” ideas. So when I pitched a raw foods spa I’d read about, they bit though back then nobody ate raw; my friends thought it meant I’d be eating steak tartare by a pool.

I don’t exactly know what I was expecting—spa treatments and beautifully arranged greens and fruit, probably–but it wasn’t what I encountered. The Hippocrates Health Institute was located in West Palm Beach, which is a lot grittier than Palm Beach. Think gravel and gutted strip malls instead of white sand and perfect vistas. Founded in the 1950s by raw foods advocate Ann Wigmore, it was in definitive decline by the time I showed up—all peeling pink stucco, diseased palm trees, unfilled pools, moldy wall-to-wall carpeting; pale people with insipid smiles and desperate eyes.

Shit was bleak.

At the orientation meeting, laminated folders were passed around and my heart sank. Our diet was to consist solely of raw cabbage, spinach, pea shoots, watercress, wheatgrass and cucumber juice, and sprouted grains. In between meals we would be learning about the diseases we’d apparently already incurred from eating cooked food, and submitting to regular fasts, enemas, rigorous tests of our organ function, and electromagnetic and infrared therapy to draw out the many toxins impeding our body’s “natural processes.”

There wasn’t so much as a massage table on the premises.

As our guide—40ish and clad in 70s cult whites—droned on about the benefits of eating raw I gazed around the circle sitting cross-legged on the dirty floor. These were the people with whom I’d be spending the next month of my life, and everyone looked lumpy and wan. The only other person under 40 was a blond woman with angry eyes wearing a long-sleeved floor-length dress though it was 90 degrees in the meeting room, air conditioning apparently counter-indicated for cleanses.

This woman of course was Ute, and though I could usually take people in without them noticing, she looked up and met my gaze hawkishly before I got a chance to register more than a general dislike for her.

At “dinner” that night, she dropped her tray unceremoniously at the corner table where I sat alone with a paperback. “What are you doing here?” she said without any introductions.

“Uh, same as everyone else?” I said.

“No,” she said and waited. I wasn’t sure if it was her German accent, her unwavering glare, or her general demeanor that made her so fucking scary but I felt unsettled though I was rarely cowed. My fear immediately morphed into anger, same as it always did.

“Have we been introduced?” I said.

“I know you’re Lisa because I was paying attention at orientation,” she said pointedly. “I’m Ute.”

“Does that come with an umlaut?” I asked.

“No.” She did not smile.

We sat silently, waiting for the other person to break. Then she asked again. “Why are you here?”

“Why are you?”

“Because I have cancer, like everyone else here but you, I’m guessing.”

What the fuck. I looked around at the chatting groups. It was the standard sadsack hippie crowd you found in ashrams and healing centers in the 1990s—a lot of birkenstocks and bad baggy clothing. Most didn’t look well, but wasn’t that why people sought out a cleanse? There were a lot of odd short dos—what your scalp looks like a few moths after you shaved it–but back then a lot of people in om-shanthi communities rocked variations on the Sinead to distance themselves from materialist mainstream values.

“You’re mixing up what people look like on chemo with what people look like when they have cancer,” she said though I still hadn’t uttered a word.

“Don’t you have to do chemo if you have cancer?” I said.

She rolled her eyes. “Almost everyone is here because they’ve given up on conventional medicine or conventional medicine has given up on them. This is our last stop.”

I focused on the green shit piled on my plate, heart pounding in my throat. This was definitely not in the brochure.

“I don’t think for you, though,” she said. I noticed others were listening in. Had she been dispatched?

“I’m here to write an article. I’m not sick.”

“Everyone’s sick,” she said, and moved to another table.

At breakfast she joined me again, though she offered no more social niceties than the day before. “I have cervical cancer stage 4,” she said.

“Is that bad?” I asked.

“I can’t tell if you’re dumb or just spoiled.”

“Okay,” I said, and didn’t know what exactly what I was attempting to convey. Okay, enough of you talking to me like the Nazi that you clearly are? Or okay, yes, I’m a spoiled bitch here to observe the cancer animals in their natural habitat.

Probably okay, both.

As the day progressed, she stuck by my side, hissing in a harshly accented, nonstop stream throughout the workshops and meals. How her cancer had surfaced three years ago; the symptoms, surgeries and various chemo rounds she’d experienced since; how she planned to survive it all and appear on talk-shows to teach people about how they could survive too. And how true-blue her husband had been throughout.

That’s when I stopped her. I’d been enduring her like a gnat uniquely equipped to make me simultaneously guilty, repelled, and angry but I knew next-level romantic bullshit when I heard it.

“You don’t seem married,” I said.

“What do you know?” she said, and moved away from me for the rest of the day. I was relieved to eat dinner in silence but afterward sat shaking for what seemed like forever in my damp, humid room. There was a lot I didn’t want to be alone with.

The next morning, I pushed my breakfast tray next to hers at a crowded table. “Hi,” said a small woman with gauze wrapped around her throat and clavicle. She had a bright smile and a mop of salt and pepper hair. “You’re the journalist from New York.”

Ute smiled cheerlessly when I looked over at her. So she’d been talking about me. Immediately the woman began testifying as well. Her name was Nancy, she was from Maryland, and soon after her breast cancer had arrived, it had metastasized to her lymph nodes and liver, which was probably what was going to kill her. When she stopped talking, an older heavy woman—Eileen from Maine–began: also metastasized breast cancer, now in her brain, she was considering euthanasia when she lost her sight. One by one, each person at the table listed their diagnoses, cancer journey, likely death. Was this how they introduced themselves to everyone here?

No, this is how they talked to young journalists who might memorialize their struggles.

I wanted to tell them that the magazine I wrote for was bullshit. That I was bullshit—calmly smiling and nodding while inside crawling out of my skin wondering if all this cancer was contagious though there was no logic my fear. I was well accustomed to people desperate to wrest something from me, but never had been around so many with an expiration date clearly labeled on their forehead.

Then I looked at Ute who was glaring at me again. God, she knew. “Asshole,” she mouthed.

It was a relief.

———————–

It’s really hard to re-animate Ute through my faulty memory—not because she doesn’t readily appear but because now I identify more with her than myself at that age. Honestly this is less of a time capsule than a wrinkle in time since I so fully feel haunted by her. She was a force then and more of a force now. I think I need to write about her so I can unleash the power neither of us could access while she was alive. Because I’ve felt sick for nearly a month now, and though at first my symptoms were fairly clear-cut, they’ve morphed into free-floating anxiety, trauma unleashed by an unholy clusterfuck of so much physical isolation, a malady in Freudian netherlands, national instability and injustice, and extended contact with key past toxins. It’s hard to write about, harder to talk about. But as always I am trying to write my way through this pain, this fear, this anger that is clutching what should be my privates but have felt since birth as if they’ve been exposed for all the world to know. Tomorrow I will dive deeper into the memories that I had thought were not mine. It’s my only way through, which means it’s my only hope. Feeling like this is not a long-term option.

And yes I’m doing zoom therapy like three times a week.

———-

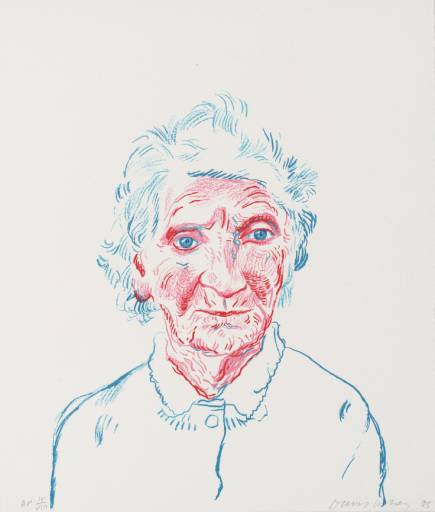

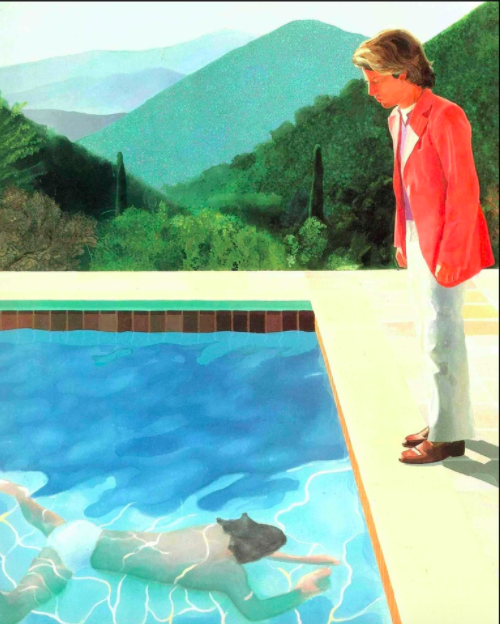

All art by David Hockney.