I just came home from a bad night a bad week a bad year so far, who am I kidding? Stopped at the bar at the corner before I came back because I had no booze in the house and it seemed wise to take the edge off all the pistons misfiring–the fight I had tonight, the hot-hot-hot flamenco to which I bore witness, the revelation that my burning love for someone had been a tiny subplot in his burning love for someone else. So yes tequila tequila before entering my house. (Don’t want to scare Grace.) Continue Reading →

I just came home from a bad night a bad week a bad year so far, who am I kidding? Stopped at the bar at the corner before I came back because I had no booze in the house and it seemed wise to take the edge off all the pistons misfiring–the fight I had tonight, the hot-hot-hot flamenco to which I bore witness, the revelation that my burning love for someone had been a tiny subplot in his burning love for someone else. So yes tequila tequila before entering my house. (Don’t want to scare Grace.) Continue Reading →

Archive | Essays

Space Crone Sob Stories and Secret Shames

I wake with a Laurie Colwin quote flashing in my mind’s eye.

I’m always smartest when I first wake up. My ego’s still out of the picture and I’m open to the divine intelligence that supports us even when we don’t support ourselves.

So the Laurie Colwin quote: “There’s a difference between privacy and dignity but they look the same.” I don’t even have to think about why that quote is showing up now. I’ve been totally sequestered, and that line explains why. In short, I’m ashamed, and it’s easier to stay out of everyone’s eye while I feel this way.

In general, I’ve never given a huge shit what people think of me. I wasn’t out of grade school before I realized everyone’s too busy worrying about how they are being judged to judge anyone else. By my 30s I stopped taking self-esteem cues from other’s interest if I didn’t reciprocate it; the futility of all that hope and will just made me sad.

But I don’t like people feeling sorry for me.

Sympathy to my mind is inherently distancing. Empathy I can bear; empathy is what I bear. But I don’t offer sympathy, ever, and I don’t appreciate being on the receiving end of it. Sympathy is just so condescending. It says: I see you in that hole and god knows I wouldn’t want to be in it so I feel bad that you are. Empathy says: I’m in that hole until you climb out, and I’ll love you no matter where you are. Continue Reading →

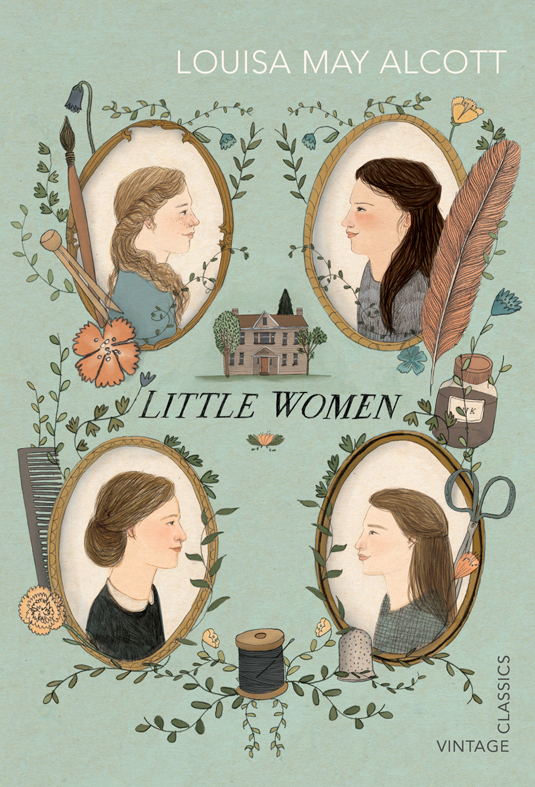

The Jo March Effect

To know Little Women is to love Little Women. From its very first line – “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents” – Louisa May Alcott’s landmark 1868 novel about four cash-poor, rich-in-spirit sisters has captured generation after generation’s love and devotion. The book’ got it all: cozy escapades, romantic triangles, “operatic tragedies,” and delicious descriptions of puddings, velvet gloves, and those infernal pickled limes. There’s pretty, maternal Meg. Artistic, vain Amy. Shy, musical “Poor Beth.” And Jo, the strapping, temperamental tomboy who aspires to be a writer when she grows up.

To know Little Women is to love Little Women. From its very first line – “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents” – Louisa May Alcott’s landmark 1868 novel about four cash-poor, rich-in-spirit sisters has captured generation after generation’s love and devotion. The book’ got it all: cozy escapades, romantic triangles, “operatic tragedies,” and delicious descriptions of puddings, velvet gloves, and those infernal pickled limes. There’s pretty, maternal Meg. Artistic, vain Amy. Shy, musical “Poor Beth.” And Jo, the strapping, temperamental tomboy who aspires to be a writer when she grows up.

Just like everyone is a Charlotte, Samantha, Carrie, or Miranda today, everyone was once a Meg, Amy, Beth, or Jo. I suspect everyone secretly loved the slapdash Jo most; there’s a reason Kate Hepburn played her in the film adaptation.

As an aspiring writer in elementary school, I adored all the sisters and clamored for the “Pilgrims Progress” morals that Alcott, a true daughter of the Transcendentalists, sewed into their scrapes and graces. But the book most came alive when Jo galloped to the forefront. Loyal to a fault, indifferent to the domestic arts, and giving no fig for her appearance, she wrote volumes while decked out in the “scribbling suit” that prompted her family to ask, “Does genius burn, Jo?” As her sisters married or passed away, Jo clung to her dream of becoming a lady author, submitting her work for prizes and publication and even moving to New York City from Massachusetts to make a real go of it.

But as many times as I pored over the book, I usually stopped reading before its very end. It wasn’t because spoiled Amy won Laurie’s love and baubles after Jo spurned his affections. It wasn’t because of Beth’s sorry decline. It was because Jo married Mr. Bhaer, the German scholar who dismissed her writing out of hand. Although the first half of Little Women (the good part, I always thought) comprises a book composed by Jo in the second half, she lays aside her writing to become his wife and the mother of two boys.

This killed me, and I don’t think I’m the only one who felt that way. I was hungry for bildungsromans about budding female writers, and the taming of Jo March dashed my dreams. It seemed so odd that her fate was portrayed as a happy ending. I viewed Beth’s death as less grim. Continue Reading →