Growing up, “soft” was an insult. The ultimate one, actually. In my family it was an umbrella term that meant out-of-shape, clueless, indolent, addled, un-vigilant, prissy, overly sensitive, entitled. You were soft if you didn’t take it on the chin. Soft if you asked for a ride when you could walk. Soft if you whined “I can’t.” Soft if you couldn’t run a mile or sported a gut. Soft if you cried when you dropped your ice cream. Definitely soft if you were a tattletale.

Every usage of the word was anathema to us, and by “us,” I am referring to my dad and thus my little sister, my mother, my myself—my father’s subjects, the peasants to whom principles came down by edict.

Soft hands meant you lacked a work ethic, the might or tenacity to do physical labor. A soft voice meant you were namby-pamby, couldn’t assert yourself. Being soft-hearted meant you were a sucker. There was a long list of what was soft, and crowing it were the rich people in my Greater Boston town, which literally had a “wrong side of the tracks” since the Mass Pike divided the more working-class sections from the wealthier people on the Hill. The rich girls wore expensive rugbys and braids, had sleepover parties with cutesie PJs, whispered about their crushes. The girls in my neighborhood wore tight designer jeans and feathered hair, hung out at the corner store, had boyfriends with whom they did a lot more than hold hands though we were all years before puberty.

Though gentle, Charlie Bucket was not soft, which is why he inherited the Chocolate Factory. Harriet the Spy was not soft; all you had to do was look at her work uniform and know she was tough as nails. In those slippers and knitted sweaters, Mister Rogers and his braying singsong were ridiculously soft. And the Beatles, oy the Beatles. With their thin voices, those fa-la-la proclamations of love—forget it. So soft. As a matter of fact, all white music was soft, except punk rock and, of course, the Stones. With their big bass lines and bigger tongues, the Rolling Stones were hard in every sense of the word. Before I even understood what sex entailed, I groked that the Beatles were the equivalent of making love and the Stones were all about fucking. Which, by definition, was not soft. (It took me a lot longer to recognize how racial commodification and femmephobia tied into my received notions of softness.)

As a kid I might not have been familiar with the more salacious connotations of “hard” but I’d learned from grownup books that the word also could be an insult: a woman deemed “hard” was viewed as scheming, weathered, unfeminine in some way. Fundamentally undesirable, which is why I wanted to be hard so much so that I did set after set of pullups on the monkey bars, played Girls Chase Boys with a ferocity that stripped the schoolyard game of all its fun, and pronounced pink “a girl’s color.”

It went without saying that being girly was, like, so soft. I foreswore Barbies and mocked the girls in my classes who did not. I swaggered rather than skipped. I refused to wear dresses, though I loved them so much that I’d occasionally pretend my mother forced me to layer a pink lacy one over my standard sweatshirt, jeans, converse sneakers. Under three layers in my sweater drawer, I hid my security blanket, which despite everything I could never give up. I tried not to smile very often though my natural inclination was to grin at everything.

Smiling was wicked soft.

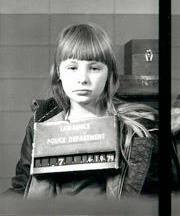

It was during this period that this mugshot of me was taken. My dad had a police photographer friend from his hometown of Lawrence, Massachusetts, a city often voted worst in the United States, and I begged him to take my picture. Looking tough seemed like an especially good call since I knew I wasn’t pretty or cute and had decided I vehemently did not care. I figured I’d just whale on anyone dumb enough to pick on me for my lack of good looks.

In retrospect I can see that with the unwashed, lanky hair that my mother cut absentmindedly, my James Dean pout, and my deadened eyes, I might not have been pretty but was an oddly sensual-looking little kid. About as un-innocent in appearance as an 8-year-old could be without strapping on Taxi Driver Jodie Foster gear. It was a sensuality that spoke of a caginess I’d already developed out of necessity. Neither trait made my life any easier amongst the alleged grownups in my life.

All the more reason not to be soft.

Now that I am a grownup lady, I have a different take on softness, one more like that wonderful Mary Oliver stanza.

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

It’s taken me decades to shed some layers of protection I donned in the early years of my life, and I’m sure I won’t be done shedding for decades more. In the interim I’ve learned to treasure softness–the sleek fur of my kitten, cozy fabrics, pliant couches, easy breezes, tender hearts, quiet ways, the caresses of gentle men and, yes, gentle women. Even the curves of my own form. I still prefer people who’ve earned their stripes but I most treasure those who’ve remained open and receptive in the face of life’s greatest challenges. Now I regard softness as the ultimate goal, the embodiment of Mary (both Marys) and all the divine feminine energies to whom I most frequently pray.

I even, dare I say it, love the softness of the girl in this mugshot—the fissures in her veneer, the not-entirely suppressed sensitivity that, rather than being her weakness, ended up being her saving grace.