This interview was originally published in Word and Film.

This interview was originally published in Word and Film.

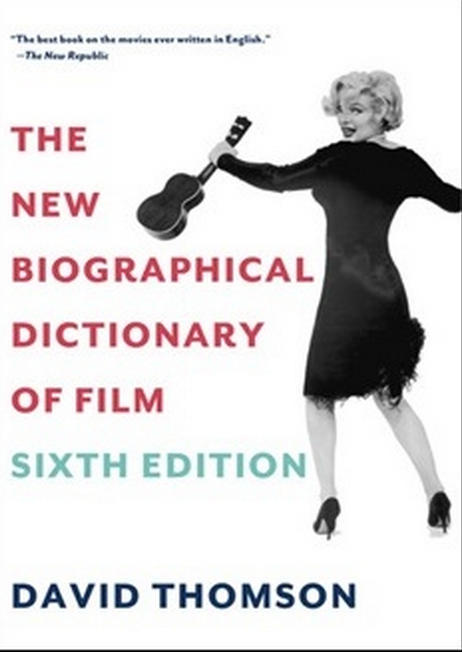

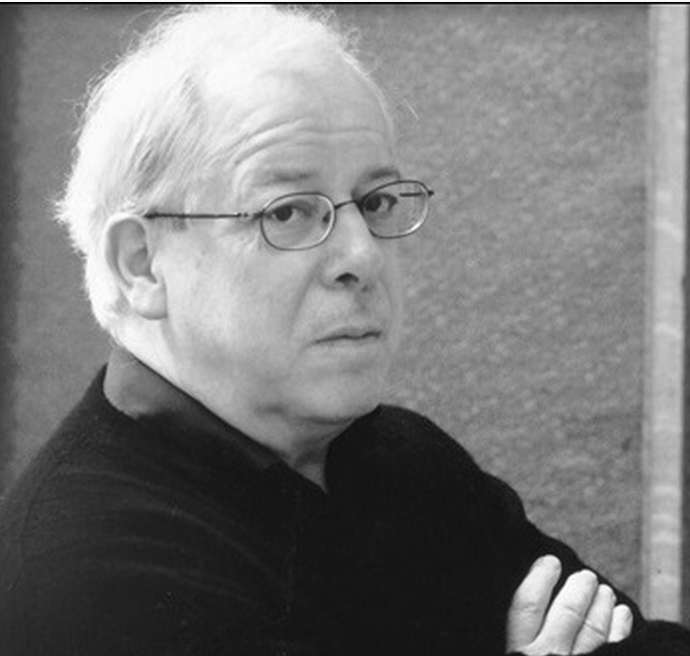

This year marked the release of the sixth edition of David Thomson’s New Biographical Dictionary of Film, published for the first time in 1975. Now at 1,154 pages long, the book isn’t just a reference manual. It’s an exotically rare bird, with more than 1,400 bios that are highly, deliciously subjective – a series of mini-reviews, remembrances, and essays that are as gratifying in their form as in their function. It’s no wonder that the book has a cult following that has expanded with each edition; a 2010 Sight and Sound critics’ poll ranked it the number one film book ever written. A British-born critic who now lives in San Francisco and writes primarily for the New Republic, Thomson fielded my questions with his typical droll candor.

Lisa Rosman: What is the ideal way to read your book? How would you prefer people approach it?

David Thomson: Many people speak of it as a bathroom book – and these days some people spend longer and longer in that room (happily or unhappily). Others speak of its therapeutic bedside role – and the bed can be as vexed as the bathroom. I believe people should dip and then move on to cross-referred topics and let the hours roll by. But the book is heavy now and I like the notion of readers having several copies, distributed through their homes and their lives. [British novelist] Geoff Dyer has admitted that he and his wife read it to each other in bed at night. I suspect they’re worthy of better things.

LR: There are more than 100 new entries to this edition. What additions did you make? And did you omit anybody who had been previously included?

DT: No, I don’t like to omit people just because they are dead, old, unimportant, or forgotten. Those are human conditions, after all. In choosing new entries I like to honor people whose careers have come alive in the years since the last edition, while leaving room for some veterans who were wrongly omitted for years. There will always be people left out – that is human, too.

LR: Your entry on Bryan Cranston concludes with this comment: “It’s hard to believe that the movies today would have the courage and the persistence to do someone like Walter White. Long-form television is the narrative form that has transcended movies in the way, once, the novel surpassed cave paintings.” If you publish another edition, then [Thomson has intimated he may not] would you begin to include television as matter-of-factly as you do film? And would you change the book’s title?

DT: If there are more editions to come, they have to have more TV and more mixed media in general. I don’t think the publisher would ever let me change the title – and the title was always a gesture. I think in an earlier edition I did suggest other titles.

LR: Some take umbrage with how you criticize actors’ looks. I find your commentary clever, actually, but how do you respond to these charges?

DT: I do not see how in a medium like the movies, the actual look of people can be less than vital to what the movies mean (and why those people are employed). I just did a piece for Sight & Sound on left-handedness in the movies that explores this. I like to be funny, but try not to be offensive. Yes, political correctness is an invading force – but it happens when real politics mean as little as they do now (I refer to the application of morality to governance).

LR: Along those lines, what are the biggest changes you’ve observed in film criticism over the last five decades?

DT: Well, film criticism peaked as a cause in the 1960 and ’70s, and now it is an increasingly dubious part of the media and a sadder aspect of commerce in the movies. But many people try to say useful tings about the experience. I fear the biggest problem now is the diminution of experience itself. People don’t believe in it quite as much as they once did – this goes across the board and I think it has to do with the large, creeping failure of humanism so that its values are set aside.

LR: In the very best of ways, I sense the influence of now-deceased New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael in your writings. Did you ever work with her? What critics do you admire? Who were your mentors?

DT: I knew Kael a bit, but never worked with her or was part of her group of disciples. I loved reading her, and disliked meeting her. I think the writers who most influenced me were the French writers of the 1950s: Dilys Powell and Kenneth Tynan in Britain, John Berger, Greil Marcus, Vidal, Didion, Dyer , Graham Greene – many others. But the real influences were regular writers – in fiction and nonfiction.

LR: Do you think you’d still be able to publish this book today if it wasn’t already an institution?

DT: No.

LR: You have written, “In heaven, I hope, there will be no stars, just supporting actors.” Who are your favorite working supporting actors?

DT: So many. Any quick list risks omitting people. So if I name names, be sure this is not a definitive list: Jim Broadbent, Juliet Stevenson, Lindsay Duncan, Stanley Tucci, L.Q. Jones, Bill Nighy, Eileen Atkins.

LR: Who do you think are the most underrated filmmakers (including TV showrunners/directors )? Actors?

DT: So many. Directors: James Gray. Actors: Jim Carrey.

LR: In the past you omitted Heath Ledger and (mincey) Carey Mulligan. Did you deem them overrated? What other actors and directors are overrated? How about directors? (I love your take-down on Stanley Kubrick, for example.)

DT: I think Ledger was elevated by his demise (that happens). I just saw Mulligan on stage in “Skylight” with Bill Nighy and I had never guessed she could be so good. I think a lot of people are overrated and underrated and I think the Dictionary was always drinking that whisky. Which means it can seem a touch drunk.

LR: How do you think the current crop of movie stars measures up compared to those from, say, the 1930s? The 1960s?

DT: Stardom has altered totally. So if you were young in the age of authentic stardom you were lucky. It is celebrity now and for good reasons we despise celebrity.

LR: What are the biggest blights in American film trends right now?

DT: Sequels, violence, special effects, credit sequences.

LR: Given the migration to digital filmmaking, what do you think about the future of film? How about the future of Hollywood studios?

DT: The studios have been over for decades. The future is technology and unaccountable – I think I can live without it (or do the other thing).

LR: Why do you think there’s such an onslaught of comic book movies? Do you think people make them for any reason besides cold, hard cash?

DT: Comic books are good energized scripts. They also encourage the pursuit of superficiality. Few people can really make good old-fashioned story movies – and comic books believe in that genre.

LR: Your book has been deemed the best of all bests. But what do you consider second best? What do you like to read in your spare time?

DT: I read all the time if there is time – I re-read a lot: Dickens, Zweig, Nabokov, Mailer, Didion, James, Greene.

LR: Which ten films would you choose to bring to a desert island? Which actor or filmmaker, living or dead, would you most like as company?

DT: I don’t think I’d pick any actor for company – they become the collection of their parts and not quite real people. My ten films (as of this moment): “Broadway Melody of 1940” (for “Begin the Beguine” – nothing else); “Persona”; “The Big Sleep”; “Celine and Julie Go Boating”; “A Man Escaped”; “Ugetsu Monogatari”; “Pierrot le Fou”; “Citizen Kane”; “The River” (Renoir); “That Obscure Object of Desire”; “Lola Montes” … but that’s eleven already, I think.

LR: What do you wish contemporary directors would emphasize more than they do in their films?

DT: Talk, wit, boredom, the passage of time, looking, the real relationship between people and animals, sleep, interior monologue, talk …. Dissolves.

LR: Since this edition was published, has anyone emerged who merits inclusion in a next (potential) edition?

DT: I thought last week – what an idiot I was to omit or forget Alexander Payne. And why has Noel Coward never been in the book?

LR: In honor of Lauren Bacall’s recent death, who is your favorite fast-talking dame of cinema? Who is your favorite tough guy?

DT: Stanwyck, I suppose; the young Angie Dickinson. Guys – Mitchum is unrivalled still. I like Tom Hardy a lot and he is outrageously tough sometimes and then very gentle.

LR: How many films do you see a week? How does that number measure up to how many you saw in 1975, when you published your first edition?

DT: I probably see all or parts of ten films a week. In 1975 it was about the same, but I saw whole films. Today, we watch fragments, moments, favorite scenes.

LR: How do you see most of the movies that you screen these days? What is the ideal way to see a film (including time of day?)

DT: I prefer a vast, empty theatre. Second best a vast packed theatre. But I watch them all over the place and if they’re good it always works.