To call Robyn Davidson’s 1980 best-selling memoir Tracks a travelogue is a bit facile. It’s not that it doesn’t conform to the definition of a travelogue: It is about her 1977 trek across 1,700 miles of west Australian desert with four camels and her sweetheart of a dog. But for many men and even more women, the book is also an anthem of liberation – from racism, nationalism, sexism, and from social conditioning itself.

To call Robyn Davidson’s 1980 best-selling memoir Tracks a travelogue is a bit facile. It’s not that it doesn’t conform to the definition of a travelogue: It is about her 1977 trek across 1,700 miles of west Australian desert with four camels and her sweetheart of a dog. But for many men and even more women, the book is also an anthem of liberation – from racism, nationalism, sexism, and from social conditioning itself.

Davidson writes:

The self in a desert did not seem to be an entity living somewhere inside the skull, but a reaction between mind and stimulus. The self in a desert becomes more and more like the desert. It has to, to survive. It becomes limitless, with its roots more in the subconscious than the conscious.

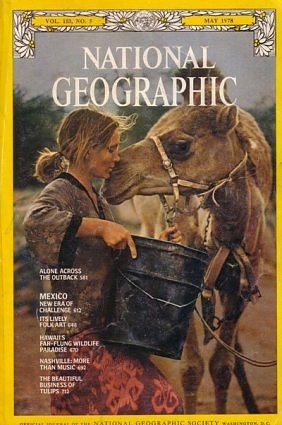

To those tired of the “Me Decade” (which has since lengthened into the “Me Decades”; is it possible we’re having a “Me Millennium?”), Davidson’s rejection of the Western concept of the self comprised the very essence of liberation. The irony was that, having achieved an egoless state out there in the outback (however fleetingly), Davidson bristled at the egotism implicit in self-documentation. Practical Aussie that she was, she still dutifully wrote up her trip for National Geographic magazine, her sponsor. She even allowed photographer Rick Smolan to capture her image as “the camel lady,” as she became known internationally. The book she subsequently wrote relayed her journey as well as the ambivalence she felt about needing anything – from other people to words themselves. It’s an unlikely subject for a bestseller, really. Unless you factor in Davidson’s glamour.

For the biggest irony of them all is that, despite Davidson’s disavowal of anything commercial, she comprised the very essence of glamour. What could be more glamorous than a woman roaming the glory of wild desert, accompanied only by a menagerie of animals? In Smolan’s photos, Davidson emerged as a total siren – all big-sky eyes, softly waving blond hair, and endless limbs only barely contained by the slips of fabric she wore. That she was an often-drunk, prickly pear who wrote about poop, camel foibles, and the shortcomings of white people, including herself, only enhanced her appeal, especially since her prose was as sharp as it was sparkling. There’s nothing like a beautiful shrew; just ask Shakespeare.

All told, it’s a wonder that it took thirty-four years to bring her story to screen. What’s even more of a wonder is that Mia Wasikowska, who portrays Robyn in John Curran’s film adaptation, channels the writer’s ornery independence without all that pesky glamour. Rather, the normally lovely Wasikowska looks as plain and obstinate as Robyn often feels – as if her beauty were dwarfed by the grandeur of nature itself (which is gorgeously depicted). Given the subject at hand, there could be no greater homage. (Somewhere, the now-sixty-four-year-old Davidson is breathing a huge sigh of relief.) Which brings us to the big reveal: In some ways, the film “Tracks” is a better embodiment of Davidson’s journey than her book is. At the very least, the medium of film makes it possible to sidestep the core contradiction plaguing the memoir: Namely, that she was forced to use words to describe her foray into wordlessness.

In general, “Tracks” foregoes unnecessary exposition. Both narratively and aesthetically, it takes its cues from the desert that Davidson is trying to become, rather than conquer. Though the less patient may experience it only as a stunning series of images (one chap exiting a critics’ screening complained, “It wasn’t really about anything”), “Tracks” is an invitation rarely proffered by a modern film: one that asks us to consider what we really need.

For the first half of the film, Robyn is still wrangling with other humans. Having hatched her plan to travel across the wilderness with her dog Diggity and four camels, she must first procure the camels (whom she will train) as well as her supplies. The twenty-seven-year-old woman works in a small-town pub, sleeps in a tent, apprentices herself to a stroppy German rancher who promises her the animals in exchange for eight months of servitude. When he welshes on their deal, she pulls her resources together partly through the help of Rick (Adam Driver), who scores her the National Geographic deal. During this section, the camerawork and dialogue is breezy, even choppy. Though it’s effective – the quick cuts emphasize Robyn’s alienation – I started to worry that the desert would be undersold the same way.

I worried needlessly. As Robyn enters the landscape, the lens immediately widens. And then widens some more. In her memoir, Davidson establishes her animals’ individual personalities but what comes across here is her oneness with them, as well as with the land across which she’s trekking. What she doesn’t feel aligned with is humanity, and the film does such a spectacular job of slowing down and pulling back – of deepening into the bright, bold silence of her environment – that we also feel affronted when she’s disrupted by tourists and Rick, who photographs her on various points of the trip.

I worried needlessly. As Robyn enters the landscape, the lens immediately widens. And then widens some more. In her memoir, Davidson establishes her animals’ individual personalities but what comes across here is her oneness with them, as well as with the land across which she’s trekking. What she doesn’t feel aligned with is humanity, and the film does such a spectacular job of slowing down and pulling back – of deepening into the bright, bold silence of her environment – that we also feel affronted when she’s disrupted by tourists and Rick, who photographs her on various points of the trip.

In a lesser film or as played by a lesser actor, Rick would come off as a white knight or a total cad. Here, we see him as Robyn does (even after she beds him): a Puckish hack who is as well-intentioned as he is meddlesome. In the last few years, Driver has established himself as the kind of live-wire who, despite his idiosyncratic features and physicality, can disappear so wholly into a role that we forget he can play any other part. He’s a fine match for Wasikowska, whose equally admirable mutability allows her a certain immutability here. His city mouse kowtows perfectly to Wasikowska’s impassive lioness.

The most remarkable moments of the film take place when Robyn is alone, of course. In her memoir, Davidson writes:

I had always supposed that loneliness was my enemy. I had seemed not to exist without people around me. But now I understood that I had always been a loner, and that this condition was a gift rather than something to be feared.

Curran shares this gift with us, rather than stealing it from her. As she treks further, the film grows slower and quieter (wisely eschewing such passages as the one above; they’d be terrible in voiceover). It also grows greater in scope.  Her irritability fades, as if it’s been bleached out by the enormous red sun overtaking everything. At a certain point, sunburnt and unhinged, she begins to resemble the desert herself. As does this uncanny film, which, in its stripped-down form, reminds us that journeys are no more than what we project on the distance between two places.

Her irritability fades, as if it’s been bleached out by the enormous red sun overtaking everything. At a certain point, sunburnt and unhinged, she begins to resemble the desert herself. As does this uncanny film, which, in its stripped-down form, reminds us that journeys are no more than what we project on the distance between two places.

For a while, Aboriginal elder Mr. Eddy (Roly Mintuma) guides Davidson through rough territory. Their time together is restorative rather than intrusive; her absorption in (and by) the land mirrors his. Ditto for the old outback couple who bathe and feed her in a respite from the most tragic chapter of her trip. It’s a worthy takeaway, one that had me weeping as the credits rolled: Communion serves us. Mere “company” does not.

This review was originally published in Word and Film.