There are few pleasures greater than revisiting a favorite film. Each time we luxuriate in its familiar glamour, we observe something new – a camera angle, a fleeting hand gesture, an aside that’s even cleverer than we remembered. Only a good book about a favorite film can actually enhance that pleasure, by pointing us to elements we’d never notice ourselves.

There are few pleasures greater than revisiting a favorite film. Each time we luxuriate in its familiar glamour, we observe something new – a camera angle, a fleeting hand gesture, an aside that’s even cleverer than we remembered. Only a good book about a favorite film can actually enhance that pleasure, by pointing us to elements we’d never notice ourselves.

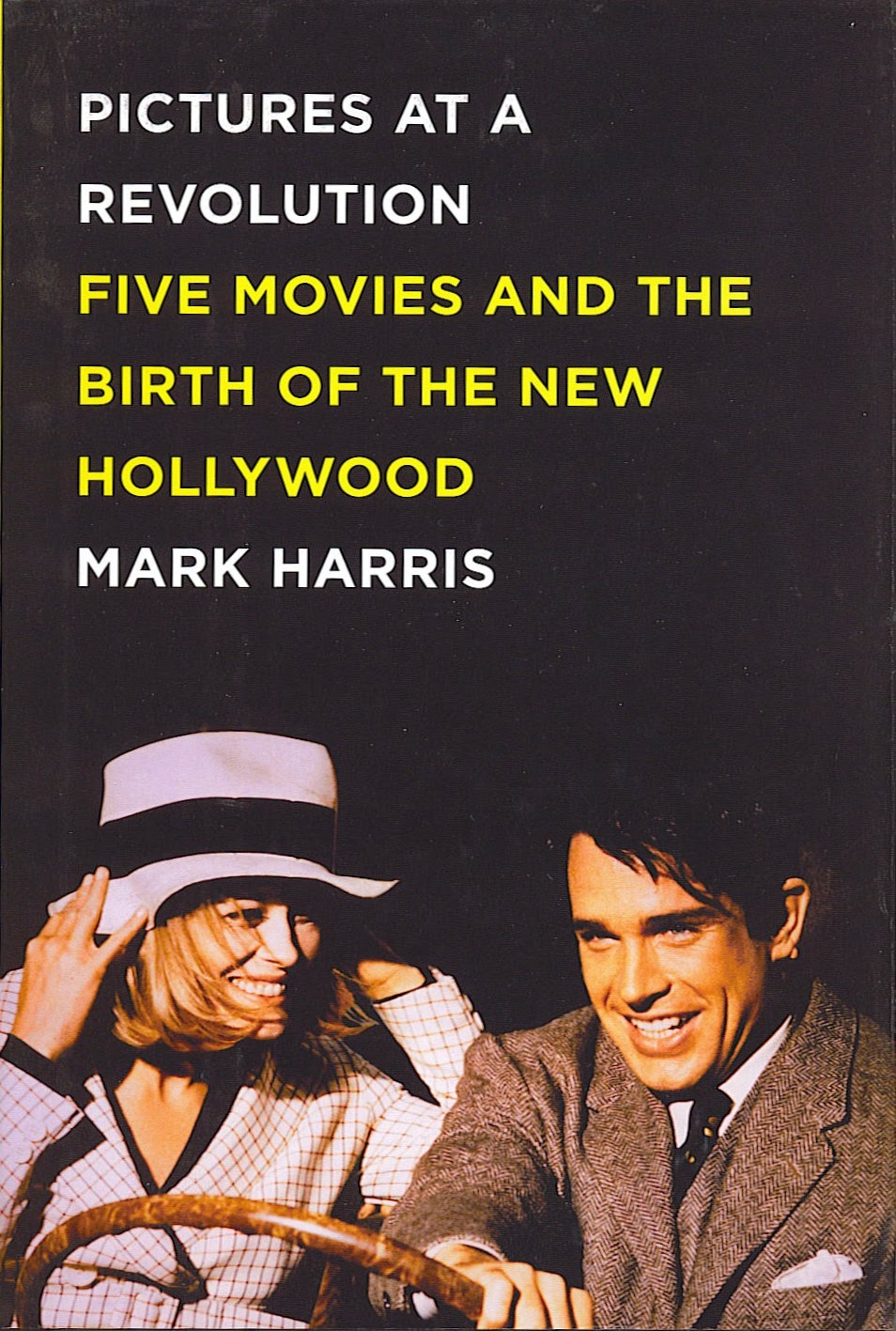

Pictures at a Revolution, Mark Harris’ 2008 look at the Academy Award nominees for best picture of 1968 (“Bonnie and Clyde,” “The Graduate,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” “Doctor Dolittle,” and “In the Heat of the Night”), is precisely that sort of book. Panoramic, insightful, chatty, and well-researched, it makes a reader feel as if she or he were in the studio board rooms, casting calls, sets, and, above all, original screening rooms of these films long before they became classics. Of the five, I’m most thoroughly and happily acquainted with “The Graduate” – mostly for the mid-sixties fashions (those fake lashes, those leopard prints!), the eminently quotable dialogue (plastics!), the staccato stammering of Dustin Hoffman, the been-there-done-that drawl of Anne Bancroft, and, oh yes, that Simon and Garfunkel soundtrack. Harris’s analysis of the film and its production – he interviewed “everyone who was anyone” who was still alive – reveals a treasure trove beneath those appealingly reflective surfaces.

For those (three?) people who’ve not seen “The Graduate,” the movie focuses on twenty-one-year-old Los Angelean Benjamin (Dustin Hoffman), who returns home from college with a pocketful of honors and no clue about what or who he wants to be when he grows up. He begins to sleep with Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), the wife of his father’s business partner. While their desultory affair persists, his parents set him up with Elaine (Katharine Ross), the Robinsons’ cow-eyed daughter. After the older woman flips out, Benjamin convinces Elaine to run away with him, only moments after she marries a handsome, blond doctor. The film is full of iconic images – Mrs. Robinson’s garter-clad gam, Benjamin adrift in his parents’ pool (in this film, no visual metaphor is left unturned), Elaine’s tear-stained face in a strip club, Benjamin plastered against the glass window of the chapel, the “what now” terror on the couple’s faces in the film’s final shot. But more than that, it captures the anxiety of a generation that was considering abandoning its predecessor’s footsteps.

It turns out how “The Graduate” was made is as fascinating as the film itself – at least as told through Harris’s eyes. (He is an extraordinary reporter.)

The script. Although, with its stretches of rat-a-tat-tat dialogue and carefully hatched scenarios, “The Graduate” may seem like it was adapted from a play, it is based upon the 1963 eponymously titled book by Charles Webb. The Graduate only sold 5,000 copies prior to the film’s release, and is mostly comprised of dialogue with few physical descriptions and even less exposition. It is also full of homophobic rants and moralistic ramblings. When director Mike Nichols first read it, his first thought was that it was “totally unoriginal.” His second thought was that he was going to make it into a movie. It was adapted to the screen primarily by his pal Buck Henry – who also appears in the film as a hotel clerk – though other scriptwriters also received credit. (Such are the wheelings-and-dealings of Hollywood.) The biggest change Henry made in his adaptation, says Harris, was to favor Benjamin’s “bumbling attempts at moral rigor over his cold, sour narcissism.” The other big change was to return Elaine to Benjamin’s arms minutes after she’d already married her blond hunk, rather thanbefore – a fix that Webb resented mightily and publicly. (Harris reports that, later, Webb marveled that he’d ever been that moralistic.) In order to ensure the dialogue was timeless, Henry admits that he tried to cut the “plastics” line. Thankfully, no one let him.

The casting. I’d thought I’d known all the big secrets in this department – namely, that then-twenty-nine-year-old Hoffman was only six years younger than Bancroft, and that he was no one but Nichols’s first choice – but it turns out that’s the tip of the iceberg. Benjamin was originally written as a big, beautiful WASP not unlike the hunk of manhood Elaine marries, and names like Robert Redford were bandied about to portray him. As Nichols remembers it, he had to tell his buddy “Bob”: “You can’t play a loser. I mean, how many times have you struck out with a woman?” (Reportedly, Redford didn’t even understand the question.) Charles Grodin was the serious front-runner but Hoffman, who at the time was just beginning to make it as a stage actor, blew everyone away in a screen test. As for Mrs. Robinson, the seemingly too-young Bancroft was no one’s first choice, either. Initially, Nichols considered Jeanne Moreau, Patricia Neal, and, most seriously, Doris Day. (Her manager/husband put the kibosh on that.) The glamazon Ava Gardner also threw her name in the hat – at forty-three, she was perfectly age-appropriate – but Nichols couldn’t imagine working with such a relic of “a fading Hollywood universe.” Most disappointingly, Gene Hackman, Hoffman’s best friend and my all-time favorite actor, was originally cast as Mr. Robinson but was fired in the second week of rehearsals – ostensibly because he was too young. It’s safe to say his career proceeded just fine.

The production. Oscar-winning Nichols may be touted as a mensch but even he admits he was a wretch during the filming of “The Graduate.” Harris reports the director preyed upon Hoffman’s sizable insecurities (he told him to clean out his nose at least once a day), loudly bemoaned Ross’s performance in shot after shot (to be fair, her lack of affect never translated into a brilliant career), and generally made the crew miserable. Bancroft often showed up to the set hungover, always bridling with the anger necessary to portray Mrs. Robinson. (Nichols says she told him years later that she “never lost that anger.”) Wisely, Nichols closed the daily rushes so she wouldn’t see he was lighting her to add years to her features. Harris also reports that a jungle theme was established for the Robinsons: from their house – all curved surfaces with a glassed-in garden – to the animal prints that Mrs. Robinson wears and the stripe in her hair. Although the great cinematographer Robert Surtees protested, Nichols insisted on “clear but impenetrable surfaces, hell to shoot.” Surtees told Harris, “I needed everything I’d learned in the previous thirty years to shoot ‘The Graduate.'”

The soundtrack. During production of “The Graduate,” Nichols listened obsessively to Simon and Garfunkel but never imagined they’d do his film’s soundtrack; they “said no to everything at the time” since they didn’t want to be considered Hollywood sellouts. Finally, he realized he had cut all the scenes to their songs, and convinced them to hand over a few songs for the film; they changed the words to a song they’d already written for “Mrs. Robinson,” and sold the rights to the already-released “The Sounds of Silence.” In retrospect, it’s impossible to imagine that Nichols would have captured the generation gap looming in this film without the duo’s soundtrack.

The reception. Although “The Graduate” is now widely touted as one of the greatest films ever made, critical reception was initially lukewarm. Pauline Kael likened it to a “television program,” though Roger Ebert, then twenty-five years old, went bananas upon first seeing it. Once the film hit general theaters, Harris reports that responses conformed to the generation gap that the film examines: Younger audiences dug it, older naysayers felt it was attacking them. (Eventually, it went on to become the twenty-first highest-grossing film ever made, adjusted for inflation.) As for Nichols himself, he disappointed Baby Boomer audiences everywhere by announcing that, eventually, “Elaine and Benjamin become their parents.” As he tells Harris, later he realized that “his unconscious [had been] making this movie.” As an Eastern European immigrant who had fled the Holocaust with his parents, he had written himself into the story by “turning Benjamin into a Jew …. Some part of me must have known I would never get material so suited to me again.”

What strikes me most after reading Pictures at a Revolution is that the appeal of “The Graduate” endures because, really, it is not about alienation from any particular era. It is about alienation from ourselves, and that’s not just a social issue. That’s the human condition, all wrapped up in the shiniest of packages.

What strikes me most after reading Pictures at a Revolution is that the appeal of “The Graduate” endures because, really, it is not about alienation from any particular era. It is about alienation from ourselves, and that’s not just a social issue. That’s the human condition, all wrapped up in the shiniest of packages.

This article originally appeared in Word and Film.