We denizens of the 21st century sometimes forget history isn’t as linear as chronological time – at least in terms of the progression of civil rights. We tend to believe, for example, that women have it better now than ever before. Certainly we assume females wield more political clout in this day and age. After all, just look at Hillary Clinton or Elizabeth Warren or, um, Sarah Palin. Right?

We denizens of the 21st century sometimes forget history isn’t as linear as chronological time – at least in terms of the progression of civil rights. We tend to believe, for example, that women have it better now than ever before. Certainly we assume females wield more political clout in this day and age. After all, just look at Hillary Clinton or Elizabeth Warren or, um, Sarah Palin. Right?

Wrong. The most radically powerful female leader to date may be a woman who ruled Egypt more than 3,000 years ago with very little fanfare and less ill happenstance. I’m not talking about Cleopatra, whose reign was as troubled as it is fabled. (Mostly she used her great sexuality in an ill-fated attempt to save her country from mass servitude.) I’m talking about Hatshepsut, who ruled Egypt for twenty years (practically a millennium in 1500 century BC) and who went so far as to refer to herself as a “female king” rather than a queen, which then connoted the head wife of a male pharaoh.

Hatshepsut is widely accepted to have led her nation into its most prosperous and peaceful era. Yet this is not a woman we learn about in school. Frankly, were it not for Egyptologist Kara Cooney’s new biography, The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt, I still would not have heard of her. “Hatshepsut has the misfortune to be antiquity’s female leader who did everything right, which may be what dooms her to obscurity,” writes Cooney, who goes on to suggest history prefers to emphasize women who mishandled their power. In other words, is it any surprise that we hear about Cleopatra rather than Hatshepsut?

It’s time to rectify this glaring omission. Arguably, history is backsliding again – reproductive rights are being repealed; young female activists have been forced to reinitiate an anti-date rape movement; and the nation seems collectively confused about the very definition of “feminism.” A big Hollywood biopic about a charismatic female leader – a woman of color, no less – could put things in perspective. The good news is that, despite the fact that history hasn’t been interested in Hatshepsut, she is very interesting, with all the makings of a timeless yet terrifically relevant epic. In fact, the biggest challenge of an adaptation of The Woman Who Would Be King wouldn’t be jazzing up this story for modern consumption. It’d be sidestepping an NC-17 rating, and finding a contemporary woman with enough grandeur to do justice to this overlooked pioneer.

Consider the possible movie treatment.

Incest

In order to keep power within families, it was common practice to marry siblings or even parents. In her very early teens, Hatshepsut married her half-brother, King Thutmose II, whose parents in turn were brother and sister. When Thutmose II died (incest not exactly boosting the health of an already-sickly family line), Hatshepsut went on to serve as co-king with her three-year-old nephew and stepson Thutmose III. (He served as her junior king, a not unheard-of practice of the day, although not with a woman.) It was a post she held until her death at approximately age forty. Note to Hollywood: Not sure about this plotline? Dude, no one complained about “Chinatown”!

Sex with Gods

In addition to marrying Thutmose II, Hatshepsut was the wife of the God Amen. This meant that it was her duty to regularly masturbate him in order to secure the fertility, wealth, and health of her people. At the time, statues formed of gold and silver with fully erect phalluses were believed to be deities. (Imagine the fun modern museums have with these relics.) Cooney reports that Hatshepsut would regularly engage the statue of Amen in a religious ritual that entailed exposing herself to his figure and bringing him to orgasm. (The details are admittedly a little fuzzy.) It was this “relationship” that helped establish her as the divine leader of Egypt as she transitioned from queen to king; she claimed Amen had mingled with her brain and chosen her as her nation’s true leader. Note to Hollywood: Everyone is fascinated with bizarre religious practices. Just look at Scientology!

Public Sex

Marriage was not about such frivolities as romance or emotional security. It was about economic security and power, and reproduction was its cornerstone. Thus, whenever Hatshepsut consummated her relationship with Thutmose II, Cooney hypothesizes that everybody and their brother were present to ensure all details were correct. Talk about performance anxiety. Note to Hollywood: Good luck getting an R rating for these scenes!

Money Talks

No one complained about the obvious aberration that was Hatshepsut’s kingship because she was a brilliant leader. During her two decades as king, she created countless jobs, vastly improved trade sanctions, and focused more on building and restoring monuments and festivals throughout Egypt and Nubia than on conquering new lands. In short, she kept everyone in line by keeping them well-paid and well-entertained. Note to Hollywood: The party scenes in this movie would put “Gatsby” to shame.

Gender Fluidity

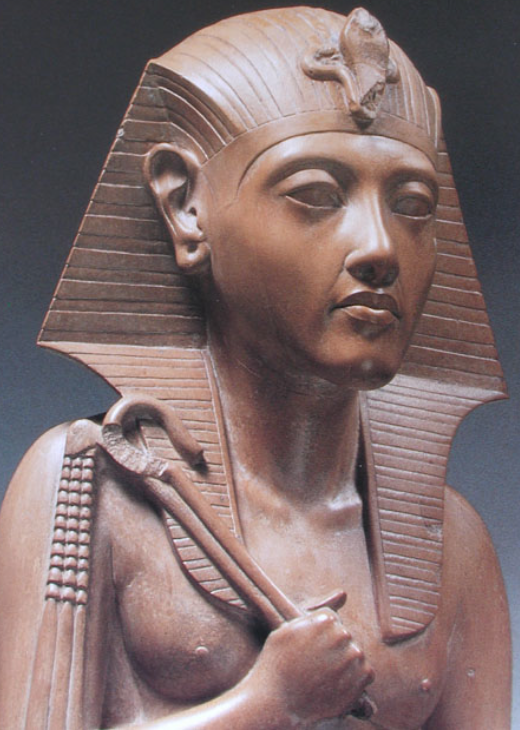

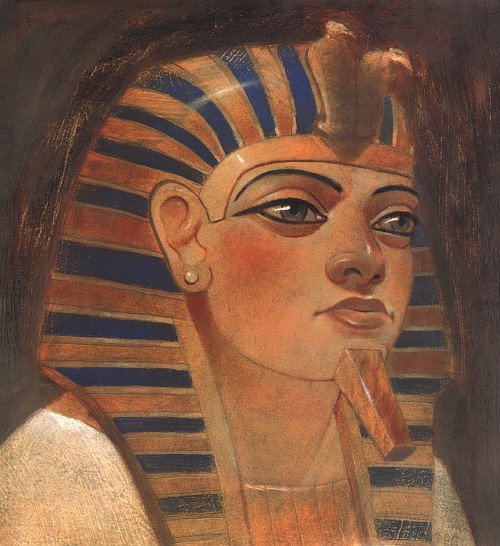

When Hatshepsut became queen, she was depicted as a traditional – and traditionally pretty – Egyptian woman. Even when she became co-king with Thutmose III, Cooney reports Hatshepsut took pains to establish she was a “female king” by wearing feminine dress and taking on a throne name that referenced a goddess rather than a god. In order to preserve her power as Thutmose III matured, though, she took on male attributes lest her nation prefer to be ruled by a man. She donned beards, men’s wigs and clothes, and even revealed her chest as was the custom of male kings. (Apparently everyone pretended not to notice her breasts.) What’s more, she began to refer to herself as the “son [rather than daughter] of King Thutmose I,” thereby suggesting that her right to the throne came from a traditional male lineage. The only problem: She could not produce an heir to continue that lineage. Since she claimed to be a male king, she herself could not give birth but she also could not muster up the equipment necessary to knock up someone else It’s possible that impregnanting a woman is the only thing Hatshepsut could not do. Note to Hollywood: hot topic alert!

When Hatshepsut became queen, she was depicted as a traditional – and traditionally pretty – Egyptian woman. Even when she became co-king with Thutmose III, Cooney reports Hatshepsut took pains to establish she was a “female king” by wearing feminine dress and taking on a throne name that referenced a goddess rather than a god. In order to preserve her power as Thutmose III matured, though, she took on male attributes lest her nation prefer to be ruled by a man. She donned beards, men’s wigs and clothes, and even revealed her chest as was the custom of male kings. (Apparently everyone pretended not to notice her breasts.) What’s more, she began to refer to herself as the “son [rather than daughter] of King Thutmose I,” thereby suggesting that her right to the throne came from a traditional male lineage. The only problem: She could not produce an heir to continue that lineage. Since she claimed to be a male king, she herself could not give birth but she also could not muster up the equipment necessary to knock up someone else It’s possible that impregnanting a woman is the only thing Hatshepsut could not do. Note to Hollywood: hot topic alert!

Which leads us to casting this potentially earthshattering biopic. We could dicker around but it’s just so obvious who Hollywood should enlist as The Woman Who Would Be King: Kerry Washington. She already plays Olivia Pope, who is TV’s female pharaoh. Like Hatshepsut herself, Washington will do whatever necessary to get this job done right. What’s more, she’ll look amazing – dare I say regal? – as she did so. Note to Hollywood: What are you waiting for?

This essay originally was published in Word and Film.