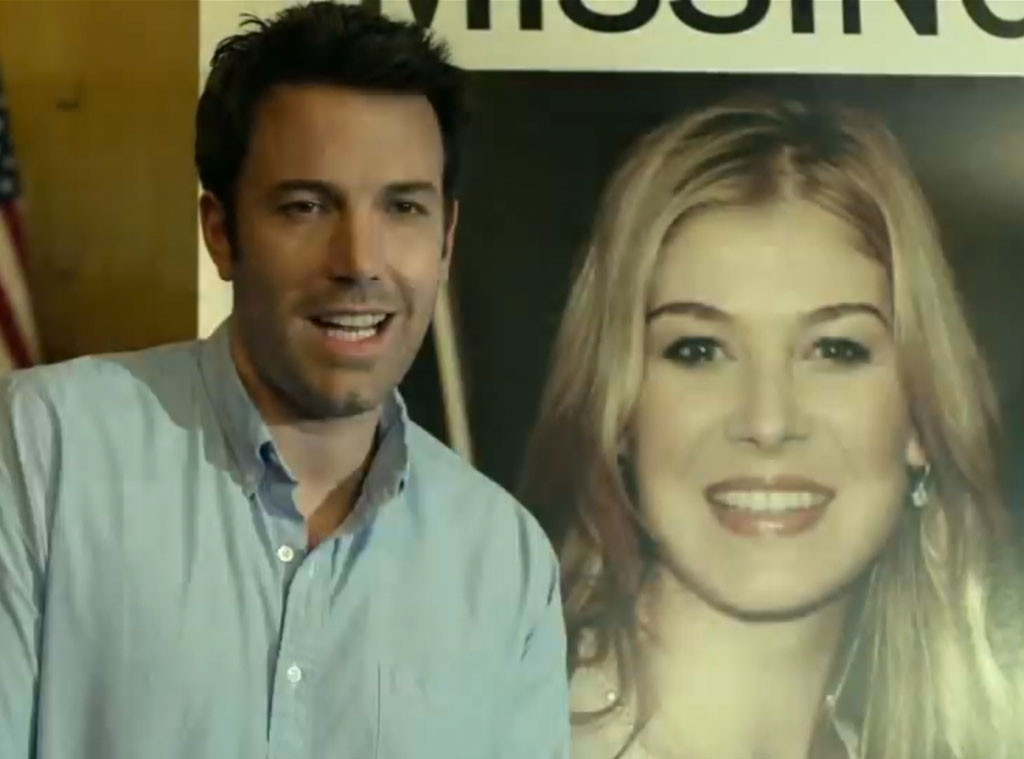

Who can forget Ben Affleck’s acceptance speech at the 2013 Academy Awards? “Marriage is hard,” he declared while thanking wife Jennifer Garner, and the audience collectively froze. The next day, Oscar post-mortems were dominated by a debate about the actor-director’s words: Were they inappropriate? Were he and Garner having trouble? Is marriage hard? Imagine an entire movie launched from that declaration – complete with Affleck’s cheesy, unsettling grin – and we’ve got “Gone Girl,” David Fincher’s extraordinary adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s eponymous bestseller.

Who can forget Ben Affleck’s acceptance speech at the 2013 Academy Awards? “Marriage is hard,” he declared while thanking wife Jennifer Garner, and the audience collectively froze. The next day, Oscar post-mortems were dominated by a debate about the actor-director’s words: Were they inappropriate? Were he and Garner having trouble? Is marriage hard? Imagine an entire movie launched from that declaration – complete with Affleck’s cheesy, unsettling grin – and we’ve got “Gone Girl,” David Fincher’s extraordinary adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s eponymous bestseller.

Though few deny that Fincher is a technically proficient director, charges of misogyny and misanthropy have dogged his films since 1995’s “Se7en,” his serial killer mystery with a biblical twist. True, his body of work – from “The Social Network,” the Sorkin-scripted Facebook origin story, to the ill-fated “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo” – doesn’t paint a rosy picture of humanity. (It’s a wonder he’s not accused of misandry.) But it’s not really humanity that gets the shaft in his films; it’s human interactions. People may need people, he suggests, but that doesn’t mean we don’t bring out the worst in each other. In this sense, “Gone Girl” – an unflinching portrait of human intimacy if ever there were one – may be his signature piece.

The irony is that some claim it’s more Flynn than Fincher. But while “Gone Girl” is more domestic in theme than his normal fare, it’s no more domesticated. In fact, with her depiction of marriage as a folie à deux, author/screenwriter Flynn may be an ideal match for the director. Not that either seem to believe in such a concept, of course.

The film itself is a complex pleasure – more savory than sweet. It opens with one of the most compelling (and classically Fincher) images of the year: a hypnagogic close-up of the golden tresses of an unidentified woman. As she turns to the camera and opens her baby-doll eyes, a male voice intones that the only way to know what’s in a person’s mind is to shatter their skull. The woman is Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike); the man is her husband, Nick Dunne (Affleck); and the marriage (naturally) is in trouble. As if to affirm this, in the next scene Nick whiles away their anniversary morning by swilling bourbon in the bar he owns with his sister (Carrie Coon).

When he finally returns to the marital McMansion, he’s met by a shattered glass table, a blood smear, and the little woman nowhere to be found. Does Amy’s disappearance mean she’s dead? And is Nick her murderer? A police investigation ensues, which doubles as an autopsy of a marriage that also may have died.

Amy is known as “Amazing Amy,” the model for her parents’ best-selling book series, and she’s never protested their plunder of her landmark moments since it funds a significant trust fund. Still, she is scarred, and only Nick can soothe her with his cocktail of adoration and genial wit – at least until the two lose their New York journalism gigs and return to his Missouri hometown to care for his ailing parents. Then, the masks they wear with each other begin to slip.

We know all this from Amy’s journal, which is excerpted in the missing woman’s slightly dippy voiceover during flashbacks intercut by a national search for her. As Nick (and his creepy smile) turns public opinion against himself, the film blossoms into a meditation on the surfaces in which we’re invested – from the media to marriage to self-perception – and whether we want to know what lives beneath them.

At 148 minutes, this is an ambitious endeavor. But Fincher seems to thrive with this suburban backdrop, perhaps because it’s the ultimate surface to pierce. He keeps us at the edge of our seats with a barrage of fade-ins and fade-outs; Flynn’s screenplay delivers twist after twist with a carefully pruned efficiency; and editor Kirk Baxter keeps apace. Still, all would be for naught if Pike and Affleck weren’t so good.

In Affleck’s case, this may be due to stunt casting – his always-palpable unease has seriously utility here – but that doesn’t make the shift of his eyes (and that smile!) any less effective. And Pike: oh my. Until this film, her rosebud features have appeared too perfectly arranged (speaking of surfaces). Here she mines them Amazingly in her dissection of the “cool girl,” that mythical being that modern men expect and modern women try to embody. When she humors the fantasies of an ex-boyfriend (a spot-on Neil Patrick Harris), we even feel her shudder.

In Affleck’s case, this may be due to stunt casting – his always-palpable unease has seriously utility here – but that doesn’t make the shift of his eyes (and that smile!) any less effective. And Pike: oh my. Until this film, her rosebud features have appeared too perfectly arranged (speaking of surfaces). Here she mines them Amazingly in her dissection of the “cool girl,” that mythical being that modern men expect and modern women try to embody. When she humors the fantasies of an ex-boyfriend (a spot-on Neil Patrick Harris), we even feel her shudder.

Despite the heft of Pike’s performance, “Gone Girl” does lose feminist nuance in its journey from page to screen; the scrapping of certain details leaves a parity by the wayside. The book’s core truth remains, though – namely, that no one knows the truth, at least when it comes to what goes on between two people. “Without you, I’m nothing,” this film croons. “With you, I may be worse.” It’s an eerily beautiful song.

This review was originally published in Word and Film.