These days, earmarking a film as a weepie is like signing its death warrant. Not only will it be scorned but its ability to make us cry will be the only criteria by which it’s judged. And there’s no winning either way: If the film does induce tears, it’s lambasted for being manipulative. If it doesn’t, it’s not adequately doing its job.

These days, earmarking a film as a weepie is like signing its death warrant. Not only will it be scorned but its ability to make us cry will be the only criteria by which it’s judged. And there’s no winning either way: If the film does induce tears, it’s lambasted for being manipulative. If it doesn’t, it’s not adequately doing its job.

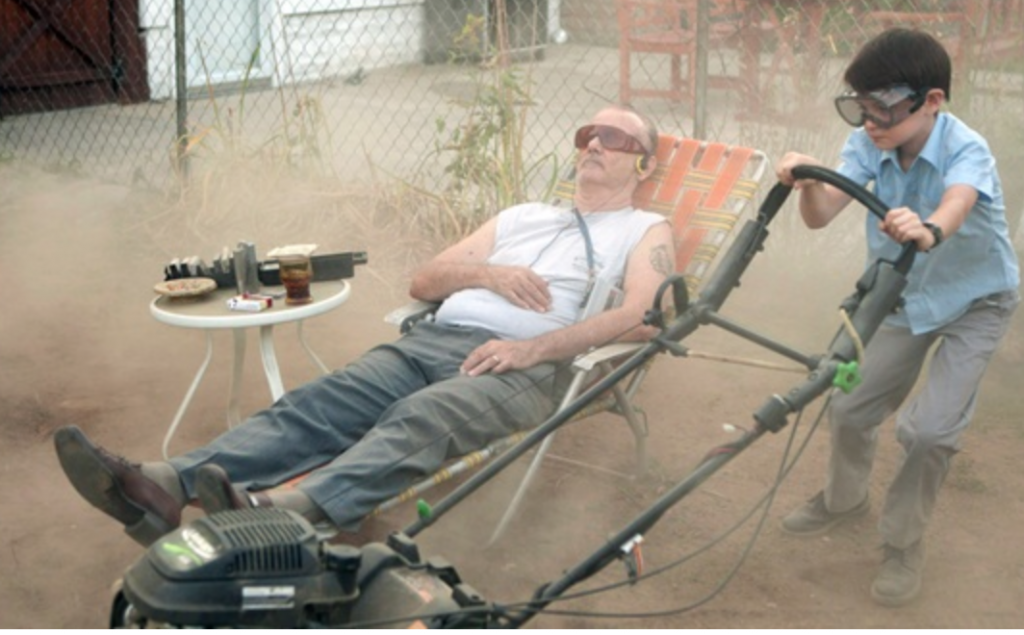

Certainly “St. Vincent,” a heart-rending indie about the friendship between Vietnam vet Vincent (Bill Murray) and young Brooklyn boy Oliver (Jaeden Lieberher), may not be receiving the high marks it deserves. Admittedly, its premise could go either way. As Vincent, the vet in question, Murray is a broke misanthrope who spends his time gambling, drinking, and shtupping a pregnant Russian prostitute (Naomi Watts) until his newly single neighbor Maggie (Melissa McCarthy) recruits him to watch her twelve-year-old son. The hapless boy blooms, and Vincent proves far kinder than he seems – if still wildly inappropriate.

A grumpy codger with a heart of gold is not exactly a new story; everyone from Billy Bob Thornton to Walter Matthau to Jack Nicholson has tried his hand at it. God knows a hooker with a heart of gold is one of the oldest film tropes around. But by now everything’s been done a kazillion times so unoriginality is hardly a deal breaker. (Cue the myriad dystopias flooding multiplexes this year.) This film boasts an expertly layered story, with such strong dialogue, editing, and casting that it earns its keep, as well as the tears it inspires. That said, it might be lost without Bill Murray.

The New Yorker critic Richard Brody recently pointed out that many of the best dramatic actors are comedians. This is true of Bill Murray, who has become a wonderful dramatic actor in the third act of his career. (His second act would be all the middling movies he did in the 1990s and early Aughts. “Space Jam,” anyone?) These days, he only works when he’s really passionate about a project, and he’s helped make the careers of such directors as Wes Anderson and Sofia Coppola (although the latter had a little family help). Now he’s doing the same for Ted Melfi, who wrote, directed, and produced this film, his first full-length feature.

The inspiration came from Melfi’s niece whom he adopted when his brother died, and it’s possible he might not have achieved the necessary directorial distance had he not wrangled in Murray. (Apparently it took many pathetic messages on his voicemail since the actor refuses to have an agent or a manager.) Once he did, he was in the clear, though, since the two reportedly shaped the project together: Murray is too honest – and too melancholy – to allow for cheap sentimentality.

The other cast members help as well. I’m not the biggest fan of Melissa McCarthy’s humor despite the fact that she’s having her moment in the sun right now, but she’s a good serious actor. She was a touchstone on the long-running “The Gilmore Girls,” and it’s nice to see her return to form. Similarly, many forget that Naomi Watts is a gifted comedic actress – she was wickedly funny in “I Heart Huckabees” and in the otherwise-unfortunate gross-out screwball “Movie 43.” Here, it’s a pleasure to watch her play a rough-edged woman, even if she seems a little too old to be accidentally knocked up. Oliver’s priest/schoolteacher as played by the always-dry Chris O’Dowd is pitch-perfect, as well.

The real news, though, is Lieberher. I worried he’d be another of those overly precious, self-conscious child actors. Instead, he possesses the grave receptivity of kids who have to soldier grownup’s emotions before they’ve learned how to navigate or even feel their own. He and Murray are terrific together since they mirror each other’s old souls.

This movie isn’t perfect. It lays it on thick at times even if some plot points that initially read as implausible are later fleshed out with an unshowiness that circumvents the hackneyed exposition plaguing some weepies. (It remains hard to believe that Vincent’s money problems would disappear after his stroke, though. Is he the only American who becomes richer upon experiencing a medical crisis?)

The degree to which audiences will overlook the film’s deficiencies has to do with the strength and generosity of Murray’s performance. Here, his eternal sadness looks like real despair – the grief of an aging generation that once defined itself by “never trusting anyone over thirty.” It shows in his gravelly working-class Brooklyn accent, his rare, rueful smile, and his raw anger, especially as he suffers the humiliation of rehabilitation. Murray is too clever to ever be accused of phoning it in but his performance here suggests unusually deep preparation.

In one haunting moment, Vincent dances in a reverie to classic rock and roll playing on his local bar’s jukebox. It’s as if Murray intersected the wild and crazy guy he was in his “Saturday Night Live” youth with Vince, who remembers using music as an escape while in Vietnam. The scene seems to capture both of their outrage at becoming the old-timers in the room since they still feel like 1960s-style rebels – a powerful moment that not only speaks for Baby Boomers but for all of us facing the passage of time.

In one haunting moment, Vincent dances in a reverie to classic rock and roll playing on his local bar’s jukebox. It’s as if Murray intersected the wild and crazy guy he was in his “Saturday Night Live” youth with Vince, who remembers using music as an escape while in Vietnam. The scene seems to capture both of their outrage at becoming the old-timers in the room since they still feel like 1960s-style rebels – a powerful moment that not only speaks for Baby Boomers but for all of us facing the passage of time.

I highly doubt Murray will be nominated for an Oscar for this performance but he does deserve one. And as much as “St. Vincent” is a crowd-pleaser with subtlety, a sympathetic portrayal of working-class people, and a legitimately tender heart, it may go under the radar, too. Critics, if not audiences, really do resent movies that make them cry.

This review was orginally published in Word and Film.