I’d always suspected I would swoon over “Hiroshima Mon Amour” (1959). It is directed by Alain Resnais, who was riding high on the French New Wave. It is written by Marguerite Duras, the French symbolic novelist widely acclaimed as a landmark feminist even if she never identified as one. It is the screen debut of Emmanuelle Riva, who was nominated for a 2012 Oscar for her harrowing performance in “Amour.” But because I thought streaming this classic on a small screen would be like eating caviar on a hamburger bun, I stayed away. Now, fifty-five years after its initial release, Rialto Pictures has acquired the U.S. distribution rights. It turns out seeing “Hiroshima Mon Amour” on a big screen is a revelation worth the wait.

I’d always suspected I would swoon over “Hiroshima Mon Amour” (1959). It is directed by Alain Resnais, who was riding high on the French New Wave. It is written by Marguerite Duras, the French symbolic novelist widely acclaimed as a landmark feminist even if she never identified as one. It is the screen debut of Emmanuelle Riva, who was nominated for a 2012 Oscar for her harrowing performance in “Amour.” But because I thought streaming this classic on a small screen would be like eating caviar on a hamburger bun, I stayed away. Now, fifty-five years after its initial release, Rialto Pictures has acquired the U.S. distribution rights. It turns out seeing “Hiroshima Mon Amour” on a big screen is a revelation worth the wait.

It begins with two voices murmuring over images of the aftermath of the Hiroshima atomic bombings. The female describes what she remembers of the disaster; the male denies her reality: You saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing. Because we are seeing images that support her memories, we are inclined to believe her, especially as the photographs of burnt, mutilated bodies, buildings, and fields are intercut with close-ups of two naked bodies, artfully arranged, artfully entwined. It seems obvious, or at least predictable: The woman’s reality is being undercut by her domineering male lover. As the two continue their back-and-forth – I saw this/ No, you did not – we begin to be lulled by the rhythm of conversation and imagery, as horrific as some of it is.

Given that Resnais had, until this film, worked as a documentarian and that Duras’s books always read like a stream-of-consciousness swirl of surrealism, it seems possible this juxtaposition of fact and fiction – this sort of prose-poem – will comprise the whole film.

Then the camera pulls back and we learn she is a white French woman, he is a Japanese man, and they are lying together in a Hiroshima hotel room. The issue of the authority of memory has been upended. Who is she to glide into this barely rehabilitated land and commandeer its pain? He is right: She saw nothing. And yet, can she not inhabit her lover’s pain as she climbs into him in other, more carnal ways?

This is the brilliance of this film. All of Resnais’s work – and Duras’s, for that matter – centers on how we shape real-life experiences through storytelling. Here is the ultimate template for such exploration. Look at how cultural imperialism intersects with gender politics, it whispers. Look at the selectivity of memory. Look at the limitations of intimacy. For that matter, Look at the fleeting nature of any shared moment. Especially the ones we experience only to savor later.

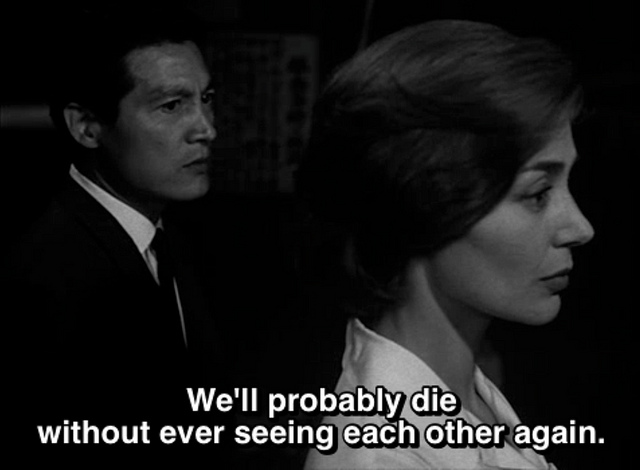

She is a film actress, in town for a two-day shoot. He is a married professional, a local. Neither are ever named. (The man is played by Eiji Okada.) Even as they make love and wander through the city – eating, drinking, nuzzling – they obsess over their eventual parting and how they will remember each other. Whether they will remember each other. She tells him about her first lover, a German solider who was killed in the Liberation. She speaks of how her head was shaved to punish her for sleeping with the enemy, and how she fled her hometown of Nevers (seriously, that’s its name), never to mention her shameful past again. This French woman and Japanese man are in the most war-savaged terrain of the twentieth century yet he is eager to discuss her trauma. It becomes clear why: Knowing her secret will mean he possesses some small part of her that no one else does. Her confidence is a token with which he can claim her, like the tiniest of wedding rings.

The two make their dramatic good-byes, only to reconvene in a different tea shop a few minutes later and make more dramatic good-byes. While they are avowing their great love, an image flashes of a younger her, shorn and locked in a basement. And so this brief affair unspools, uniting them (and us) in a reverie that is at once two days, ninety minutes, an era, an eon, and the longest of nanoseconds. Of this film, Resnais stated proudly that “he smashed time.” He was not kidding. It is an explosion that forces us to question who is telling the story, who is listening, and who remembers what.

The two make their dramatic good-byes, only to reconvene in a different tea shop a few minutes later and make more dramatic good-byes. While they are avowing their great love, an image flashes of a younger her, shorn and locked in a basement. And so this brief affair unspools, uniting them (and us) in a reverie that is at once two days, ninety minutes, an era, an eon, and the longest of nanoseconds. Of this film, Resnais stated proudly that “he smashed time.” He was not kidding. It is an explosion that forces us to question who is telling the story, who is listening, and who remembers what.

All this may sound ridiculous, even pretentious, except that the real bloodshed framing this pretty tableau validates such interrogation. (The actors’ raw emotionality does, too.) As an audience, we cannot help but feel called to the carpet somehow. Bearing witness confers a power of its own, even as the nonlinear fog of the narrative discombulates us. No matter what happens to us, it suggests, we remain responsible. Our dreams, even our nightmares, are real, and life is what we make of it. Gorgeous and yearning, “Hiroshima Mon Amour” offers a still-modern thesis: Memory, like love, is a commodity that no one fully possesses.

A version of this article was originally published in Word and Film.