The opening few minutes of “Blackhat,” Michael Mann’s first release in nearly six years, are its dullest, and I’m fairly certain that’s deliberate. Mann is a director who’s always practiced the slow burn, and a cruddy-looking, old saw of a beginning – the camera zooms through a mouse-colored maze of computer wires and microchips – is in keeping with his strain of bombastic understatement, especially in a film about the pyrotechnics of cyber-terrorists. It’s not that Mann is establishing himself as doggedly anti-technology (as point of fact, he’s not anti-technology at all); it’s that he’s setting the stage for a different kind of action movie, one in which its hacker hero reads physical books by Foucault.

The opening few minutes of “Blackhat,” Michael Mann’s first release in nearly six years, are its dullest, and I’m fairly certain that’s deliberate. Mann is a director who’s always practiced the slow burn, and a cruddy-looking, old saw of a beginning – the camera zooms through a mouse-colored maze of computer wires and microchips – is in keeping with his strain of bombastic understatement, especially in a film about the pyrotechnics of cyber-terrorists. It’s not that Mann is establishing himself as doggedly anti-technology (as point of fact, he’s not anti-technology at all); it’s that he’s setting the stage for a different kind of action movie, one in which its hacker hero reads physical books by Foucault.

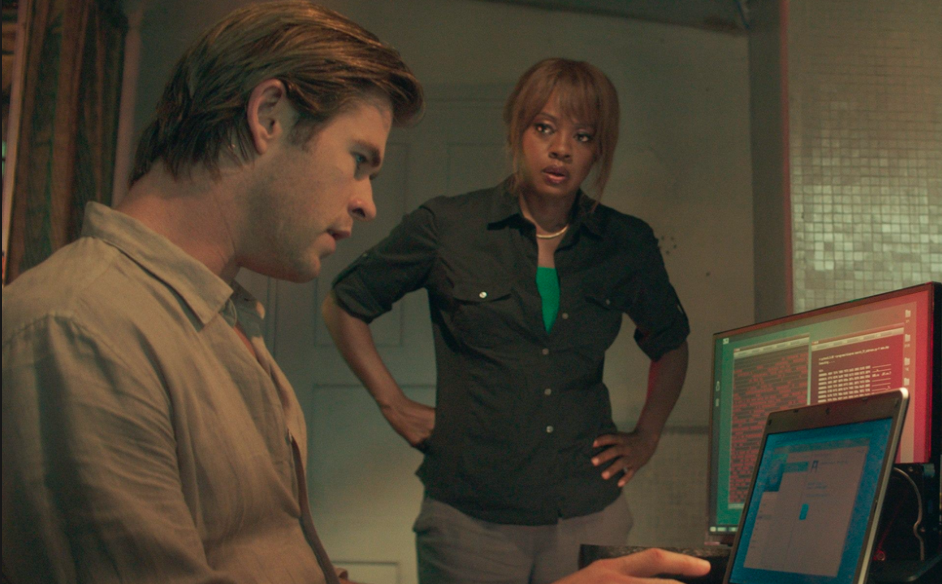

The hero in question is Hathaway (Chris Hemsworth), and we’re introduced to him after an explosion at a Hong Kong power plant and an attack on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange are traced to the same “remote access tool” (RAT). Enlisted by Chinese officials to track down the mysterious “blackhat” (slang for dangerous hacker), programmer Chen Dawai (Wang Leehom) ropes in his computer engineer sister Lien (Tang Wei) and then convinces the U.S. to release imprisoned programmer Hathaway on furlough; while undergraduate roommates at MIT, Chen and Hathaway wrote the code on which the RAT is piggybacking. Rounding out the anti-cyberterrorism team is an unblinking Viola Davis as Morgan, a fed who’s been scarred by 9/11.

There’s some everything-under-the-kitchen-sink confusion here, for sure: In addition to the shadow of 9/11, there’s the Darth Vader thumbprint of the NSA, who won’t cough up key software even when it might save millions of lives, and the precarious alliance of the Chinese and U.S. government. Add to that the inspiration for Morgan Davis Foehl’s script – an attack on an Iranian uranium enrichment plant by malware deployed through USB flash drives – and it all seems awfully timely for Mann, who usually opts for purer noir. We get the sense that he’s got a bone to pick this time around.  What’s surprising is that, rather than cramping his style – and that would be no small thing as style is substance for this director – the urgency of his social message deepens it. All his trademarks are in full effect in this film, and they’re particularly effective. The eye-of-the-storm meeting in a late-night greasy spoon: check. Tense, staccato dialogue: check. Muted oceans of sound: check. Blank white walls, neon lights, tiny jets, speedboats: check, check, check, check. Even the slicked-back hair: check. (Note to Hemsworth’s agent: That’s a good look for your client!).

What’s surprising is that, rather than cramping his style – and that would be no small thing as style is substance for this director – the urgency of his social message deepens it. All his trademarks are in full effect in this film, and they’re particularly effective. The eye-of-the-storm meeting in a late-night greasy spoon: check. Tense, staccato dialogue: check. Muted oceans of sound: check. Blank white walls, neon lights, tiny jets, speedboats: check, check, check, check. Even the slicked-back hair: check. (Note to Hemsworth’s agent: That’s a good look for your client!).

To some degree, Mann has always treated actors as part of the backdrop. Like his blank white walls, their performances are all about “negative space,” and he demands a quiet, almost characterless menace that is consistent with his overall ethos and aesthetic. (Heck, he extracted Pacino’s only subdued, post-“Scarface” performance.) Of the cast assembled in “Blackhat,” Davis seems to have studied the Mann catalog most closely, and her FBI agent is all deadpan stare and slow, deliberate exhalations. But it is Hemsworth’s Hathaway, laconic and ever-vigilant, who proves an ideal Mann protagonist; with his twenty-four pack and steady blue gaze, the Aussie is so overwhelmingly physical that he brings a naturalism to all that stoicism. If it seems unlikely for a hacker to be so hunky, it’s perfectly appropriate for this outlier, whose bad-boy brawn alienated him from the Silicon Valley crowd in the first place. (I may be rationalizing; did I mention his abs?) Very little dialogue is written for the relationship Hathaway develops with Lien (very little dialogue is ever written in Mann movies) but the pair’s steamy eye contact and those long, ropy arms he wraps around her – for his protection as much as hers – convey volumes. (I wonder: Are overseas actors nabbing more and more Hollywood roles because they exude a self-possessed manliness that evades the jumpy boyishness of U.S. male stars?)

Though the Chinese leads speak flawless English, the first language of this film is code, and it’s sort of the point that most people aren’t fluent in the computer languages now running our world. But not even Mann, who normally excels at taking us inside gearworks, can transcend the visual boredom of people clicking away on keyboards. In fact, he almost revels in that boredom, using an exceptionally shoddy-looking digital video and myriad tight closeups of people hunched over monitors. Perhaps this is to highlight the second language of “Blackhat”: the international language of loooove. For, social messages be damned, the relationship between Lien and Hathaway is the real revelation of this cyber-noir.

The love story is key to all Mann’s maximally minimalist vehicles: It lends the lone wolf hero a humanity and distinguishes between a true psycho and a person who’s been reduced by life to brass tacks. But Lien is more than a mere plot device; she’s a partner in both love and crime. Scenes of the two silently enacting a plan they’ve devised off camera are all the more thrilling because it suggests that the connection between them isn’t merely carnal. Could a benefit of the new millennium’s technology be a more equitable dance between men and women, as well as mind and body? Could co-programming be the new sexual minuet?

I’d never suggest “Blackhat” is a perfect movie – its visual shabbiness is too disappointing even if intentional, and a clumsily staged gunfight treats a crowd of Indonesians as disposable playthings – but there’s odd, stirring stuff here. Mann is going for a lot, and ultimately he is to be commended for his newest take on the B Movie, of which he remains the reigning king. His films are like slightly bad poetry: so cheekily constructed that we can see their seams, affecting nonetheless.

This review was originally published at Word and Film.