This month marks the 90th anniversary of the publication of The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s hallowed classic about a self-made tycoon and his long-lost love. Like the green light famously tantalizing its protagonist, Gatsby has proven irresistible to filmmakers, who keep adapting it to the screen but never capture its allure. Why can’t cinema get this novel right? And, perhaps more intriguingly, why does it keep trying?

This month marks the 90th anniversary of the publication of The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s hallowed classic about a self-made tycoon and his long-lost love. Like the green light famously tantalizing its protagonist, Gatsby has proven irresistible to filmmakers, who keep adapting it to the screen but never capture its allure. Why can’t cinema get this novel right? And, perhaps more intriguingly, why does it keep trying?

The answers may lie in the book itself. Published in 1925, it was initially deemed a failure, garnering mixed reviews and selling only 20,000 copies. Though now celebrated as The Great American Novel, it didn’t experience a resurgence until World War II, when it resonated with a nation clinging to its myths in the shadow of international threats. Fitzgerald himself was a bit like Jay Gatsby, dying in 1940 with a tarnished legacy that had to be restored by adherents not unlike narrator Nick Carraway. For that matter, the book itself–a reverie of furs, sleek cars, jazz, and prettily phrased quasi-revelations (reserving judgments is a matter of infinite hope)–also could be described as a Jay Gatsby, a barrage of smoke and gilt-framed mirrors that buys so completely into its hype that we buy it as well. Excessive, earnest, and, yes, a tad hollow, Gatsby is a profoundly American story, with flaws–vanities as well as cardboard romances–that loom far larger on a big screen. But it is also the quintessential rags-to-riches tale, so it remains the stuff of which Hollywood dreams are made.

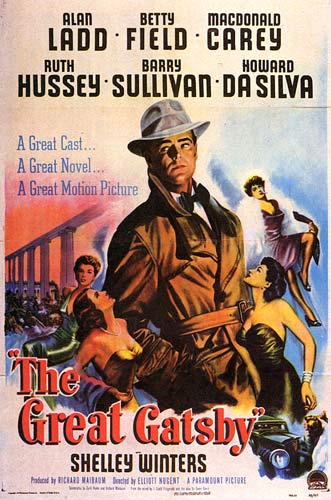

The first adaptation, made only a year after the book’s release, was a silent film. Now lost save a one-minute trailer that boasts a Jazz Age, found-footage appeal, we’ll never know if this version escaped the Gatsby curse. The 1949 remake, directed by Elliot Nugent and starring Alan Ladd as Gatsby, took liberties that mostly fell flat: It’s set in 1928 rather than 1922, Carraway marries Jordan (miss the point much?), Gatsby is a balls-out bootlegger who’s basically a stooge for a femme fatale Daisy (an amazing misread of her character), and it’s generally a hot-headed muddle of gangster and film noir tropes that reflect little of the Roaring Twenties.

But while Nugent’s film had backbone at least, Jack Clayton’s 1974 remake is a wispy, WASPy affair saddled with a sanctimonious voiceover, presumably to highlight Fitzgerald’s literary charms. Awash in 1970s-style watercolors, the usually likable Sam Waterson plays an unusually unlikable Nick, a squeaky Mia Farrow plays an exceptionally unlikable Daisy, and golden boy Robert Redford plays Gatbsy in an inspired, if too on-the-nose, feat of casting. All in all, it’s less of a moving picture than a series of paint-by-number, admittedly lovely still lifes.

The early Aughts brought some serious Gatsby misfires as well: “The Great Gatsby” (2000), a made-for-TV remake, and “G” (2002), which billed itself as a sort of hip-hop homage. The former features Paul Rudd as Nick, summoning a ruefulness he rarely taps anymore, and Martin Donovan as a brilliantly entitled Tom (Daisy’s husband Tom), but it is doomed by dull-as-dirt leads Mira Sorvino (as Daisy) and Toby Stephens (as Gatsby), not to mention hackneyed direction from Robert Markowitz. “G” is a more innovative failure, at least. In it, the tycoon has been reinvisioned as “Summer G,” a hip hop mogul living in the Hamptons, and Daisy has become “Sky” (Chenoa Maxwell), who’s married to loutish Chip (Blair Underwood). For a while, the film has enough heart to keep it alive. The further it drifts from the original text, though, the more it’s felled by an excess of suplots.

Baz Luhrman seemed the perfect candidate to finally make a good remake. Forever yearning and bombastically glittery, he’s always been a Jay Gatsby of a director. For an act or two of his 2013 effort, the match actually does work well, at least if you can accept your “Gatsby” as a 3-D diorama of confetti, champagne, and sparkly cleavage. As the titular character, Leonardo DiCaprio makes almost as much as sense as Redford did, and Toby Maguire’s overawe suits Nick as Carey Mulligan’s pretty spinelessness suits Daisy. Eventually the breathless pacing caves in on itself, though, and the film becomes, o irony of ironies, too much of a good thing. More of the original language might’ve saved it from itself.

Since then, we’ve only been burdened by “Affluenza” (20014), a micro-indie that imagines an East Egg-like Long Island community shadowed by Wall Street’s 2008 troubles. If only the film had been so micro that it never gained distribution at all; its preachy indictment is so artless that we never grasp the initial appeal of this Hamptony life, let alone the pull of the original story.

Heavily influenced by cinema, Fitzgerald was such a vivid portraitist that it’s unlikely that anyone’s vision of his book will ever match what he instilled in our mind’s eyes. But rest assured, filmmakers will continue to beat on, borne back ceaselessly into the past. Someday, one may even be successful.

This was originally published in Word and Film.