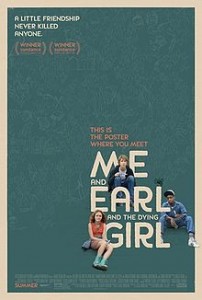

I have a theory that Sundance standouts are not necessarily the best films. Instead, they’re the ones that dare to be emotional, even sweet, since they offer a welcome contrast to the disaffected fare that proliferates the indie circuit. Take “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl,” which won the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award at this year’s festival. A whimsical tearjerker about Greg (Thomas Mann), a loner of a teenage filmmaker, and Rachel (Olivia Cooke), the titular dying girl, this is the stuff of which Sundance dreams are made; it even boasts a protagonist guaranteed to resonate with critics and festival-goers.

I have a theory that Sundance standouts are not necessarily the best films. Instead, they’re the ones that dare to be emotional, even sweet, since they offer a welcome contrast to the disaffected fare that proliferates the indie circuit. Take “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl,” which won the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award at this year’s festival. A whimsical tearjerker about Greg (Thomas Mann), a loner of a teenage filmmaker, and Rachel (Olivia Cooke), the titular dying girl, this is the stuff of which Sundance dreams are made; it even boasts a protagonist guaranteed to resonate with critics and festival-goers.

So am I indirectly saying I don’t like it? I am not. This movie is an endearing, charismatically stitched effort from director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon and screenwriter Jesse Andrews, who adapted his own eponymous YA novel. But it is also undeniably twee, and afflicted with the micro-aggression that continues to rage unchecked in Hollywood comedies. I can’t help but wonder if its thunderously positive early buzz stems from “Sundance Goggles,” that unique myopia caused by seeing five movies a day at very high altitudes.

The film begins as Greg is starting his senior year at a Pittsburgh high school. Though he’s not ecstatic about the prospect, he’s at least comfortable in his routines: He fits in with everyone but only hangs out with his anthropology professor dad (a sarong-clad Nick Offerman) and Earl (sly-eyed RJ Cyler), his best friend whom he refers to as his “coworker.” But when Greg’s mother (an unusually crunchy Connie Briton) insists he spend time with Rachel, a fellow student with stage-four leukemia, his routine falls apart fast. As she confronts her mortality, Greg is forced to face his personality limitations – his selfishness, his social anxieties, and his general misanthropy – while he races to complete a film for her before she dies.

The film begins as Greg is starting his senior year at a Pittsburgh high school. Though he’s not ecstatic about the prospect, he’s at least comfortable in his routines: He fits in with everyone but only hangs out with his anthropology professor dad (a sarong-clad Nick Offerman) and Earl (sly-eyed RJ Cyler), his best friend whom he refers to as his “coworker.” But when Greg’s mother (an unusually crunchy Connie Briton) insists he spend time with Rachel, a fellow student with stage-four leukemia, his routine falls apart fast. As she confronts her mortality, Greg is forced to face his personality limitations – his selfishness, his social anxieties, and his general misanthropy – while he races to complete a film for her before she dies.

It’s a heavy premise, for sure, and Gomez-Rejon labors too intensively to lighten the joint up. He juxtaposes naturalistic, sun-dilapidated Pittsburgh exteriors with perfectly framed, poker-faced close-ups; and brandishes cutesy title cards, meta voiceovers, straight dollies, off-kilter camera angles, and a lickety-split editing that could benefit from these kids’ ADD medication. Best are the montages zeroing in on Earl and Greg’s loving parodies of their favorite films: “Eyes Wide Butt,” “2:48 PM Cowboy,” “My Dinner with Andre the Giant,” and “A Sockwork Orange,” featuring – you guessed it – an impressive array of sock puppets. (Werner Herzog looms as these boys’ deadpan patron saint.)  A generous intelligence prevails in these homages that makes it easier to forgive the film’s hipper-than-thou tactics. Ditto for when Earl, Greg, and Rachel pour over their various screens rather than each other; we grasp how difficult it is to express emotion healthfully when you belong to a generation that’s been narrating itself through a deluge of technology and media long before it had something to say.

A generous intelligence prevails in these homages that makes it easier to forgive the film’s hipper-than-thou tactics. Ditto for when Earl, Greg, and Rachel pour over their various screens rather than each other; we grasp how difficult it is to express emotion healthfully when you belong to a generation that’s been narrating itself through a deluge of technology and media long before it had something to say.

This movie wouldn’t work at all if these teen actors were the kind to play winsome or adorable. Mann works admirably within the limitations of his role; essentially, he’s being asked to transcend a self-consciousness that the film itself never sheds. Olivia Clarke finds many shades in a character written as a bit of a blank slate; her bemused, sad eyes may be what haunt us most later. This film has a real “Earl” problem, though. With his impeccable comic timing and old-soul hyper-vigilance, Cyler offers a resonance that grounds out even the most cloying scenes. But I couldn’t help wincing over how Earl, who lives on the rough side of town with no father and an alcoholic mother, is sidelined; it’s an old saw to have a disadvantaged black character without much storyline of his own facilitate the growth of a central white protagonist. As with “Pitch Perfect 2,” it’s disappointing to see that dynamic replicated in a movie about millennials. It’s especially disappointing in this case because Andrews threw his own baby out with the bathwater; in the book, Earl is a far more developed character whose complexity often eclipses Greg’s fatuousness.

I’m not the choir to whom it’s preaching but, despite its significant failings (and atonally conventional conclusion), “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” still left me hopeful. Perhaps I’m just twentieth-century enough to be pleasantly surprised by young people who are trying to say and make things of substance.

This was originally published in Word and Film.