“The End of the Tour” may be easier to like if you’re not an ardent fan of David Foster Wallace. Adapted from David Lipsky’s eponymous book, a transcript of a five-day interview he conducted with the Infinite Jest author for a never-published Rolling Stone article, it stars Jason Segel as Wallace and Jesse Eisenberg as Lipsky in a feat of casting that’s almost too on the nose. More to the point, it is directed by James Ponsoldt, who in his films “The Spectacular Now” and “Smashed” exposed the self-delusions of addiction with the gentlest of bedside manners. Working from a script by playwright Donald Margulies, Ponsoldt has crafted a portrait of the late author’s shadows that, while still too deferential, offers flashes of honesty that far outstrip the source material – including most personal statements from Wallace himself.

“The End of the Tour” may be easier to like if you’re not an ardent fan of David Foster Wallace. Adapted from David Lipsky’s eponymous book, a transcript of a five-day interview he conducted with the Infinite Jest author for a never-published Rolling Stone article, it stars Jason Segel as Wallace and Jesse Eisenberg as Lipsky in a feat of casting that’s almost too on the nose. More to the point, it is directed by James Ponsoldt, who in his films “The Spectacular Now” and “Smashed” exposed the self-delusions of addiction with the gentlest of bedside manners. Working from a script by playwright Donald Margulies, Ponsoldt has crafted a portrait of the late author’s shadows that, while still too deferential, offers flashes of honesty that far outstrip the source material – including most personal statements from Wallace himself.

Since his “Social Network” turn as Mark Zuckerberg, Eisenberg has been the go-to guy for angry nerd roles, and he finds something new in each one. Here, with his turtle posture and twitchy features, Eisenberg nails the nervy shock of this Manhattan kid encountering his first major roadblock: Lipsky was assigned to profile Wallace’s meteoric 1996 ascent just as his own debut novel was receiving a tepid response. The unfairness of it all seems to visibly descend upon Lipsky’s already-hunched shoulders, especially when he enters Wallace’s modest Bloomington, Illinois, home – shabby rather than hipster vintage and piled high with homilies, books (mostly his own), and, rather improbably, an Alanis Morissette poster. “A lot of women in magazines are pretty but not erotic because they don’t look like anyone you know,” Wallace says to explain his crush, adding that, even now that he’s famous, he could never try to contact Morissette, not even for an innocent tea. We can see Lipsky deciding whether to buy this line.

Thus begins the two men’s dance. They like each other from the beginning – Wallace invites the journalist to stay in his house before they embark on the last leg of his tour – but both distrust liking anything. Lipsky openly craves the other man’s success but is flummoxed by his Midwestern folksiness. In turn, Wallace’s distaste for the other man’s ambition is dwarfed by his distaste for his own ego, which Lipsky also finds repellant once it assails him two-thirds of the way through their trip. Their feature-length conversation is the cinematic equivalent of a string-music minuet, with the two men lapping over each other rhythmically, screeching to crescendos and then, politely, drawing back. It also feels like finals week for a couple of freshman philosophy majors.

Thus begins the two men’s dance. They like each other from the beginning – Wallace invites the journalist to stay in his house before they embark on the last leg of his tour – but both distrust liking anything. Lipsky openly craves the other man’s success but is flummoxed by his Midwestern folksiness. In turn, Wallace’s distaste for the other man’s ambition is dwarfed by his distaste for his own ego, which Lipsky also finds repellant once it assails him two-thirds of the way through their trip. Their feature-length conversation is the cinematic equivalent of a string-music minuet, with the two men lapping over each other rhythmically, screeching to crescendos and then, politely, drawing back. It also feels like finals week for a couple of freshman philosophy majors.

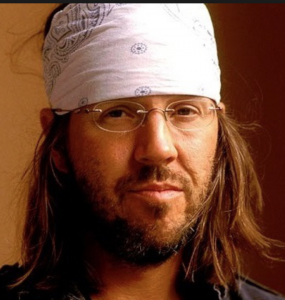

Segel’s performance is as brilliantly devious as Wallace himself. With his oversized frame, purposefully benign expression, and greasy locks contained by that trademark bandana, the actor plays Wallace as a wild animal trapped, ostensibly, by his newly hatched fame. His eyes are glazed; his gait is a Thorazine shuffle; his speech, a Slush Puppy of deliberately dropped “Gs.” He initially reads as an idiot savant but as he chatters through Heartland highways, hotels, and bookstores, he morphs into a guy who believes he’d destroy everything if he dropped that Clark Kent banality. Intent on seeming like the type of person who wouldn’t want to be profiled by Rolling Stone, he bombards Lipsky with a barrage of flattery about the latter man’s relative potential and sophistication, and often stops the tape recorder to rephrase himself.

In positioning himself next to this maelstrom of meta-earnestness, Lipsky can’t help but come off as a suspicious weasel. It’s a real-time example of what was often described as Wallace’s “asshole problem”: the seduction of his reader into loving himself as narrator and loathing the people he described. But when the two men spend a day with Wallace’s female friends (Mamie Gummer and Mickey Sumner), the more successful author’s predatory nature comes to the forefront. We can see how his eyes narrow when Lipsky puts the moves on one of the women; Wallace seems to regard both ladies as his territory.

It’s a real-time example of what was often described as Wallace’s “asshole problem”: the seduction of his reader into loving himself as narrator and loathing the people he described. But when the two men spend a day with Wallace’s female friends (Mamie Gummer and Mickey Sumner), the more successful author’s predatory nature comes to the forefront. We can see how his eyes narrow when Lipsky puts the moves on one of the women; Wallace seems to regard both ladies as his territory.

Ponsoldt and Margulies really draw out these moments, which are barely glanced upon in Lipsky’s too-reverential book. They also linger over how Wallace never cops to his addiction struggles. Perhaps to impart a more conventional dramatic arc, Lipsky gradually works up to asking whether Wallace is the reformed junkie he’s reported to be. Wallace’s circumvention of the topic sounds like grand-standing rather than a protection of his privacy; he waxes rhapsodic about his valiant struggles with existential depression but can’t acknowledge himself as anything so quotidian as an alcoholic. (D. T. Max’s Wallace biography, Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story, reports the author’s rehab stints and AA membership as fact.) Eventually, Wallace’s love for junk food, junk TV, junk movies – greatly detailed against the drab Midwestern winter backdrop – begins to feel less like a bid for simple comfort and more like an appreciation of anything that reinforces his sense of superiority and Chicken Little-ness.

The film never goes so far as to call bullshit on Wallace – to confirm the existence of his addictions, for example – but it does distance itself from the cult of his personality. We never hear him read from his work, for instance, and we observe his aw-shucksiness mysteriously disappear in radio interviews. (Behold those newly discovered “Gs!” Behold the genius of his self-promotion rather than his novels!) In a tenth-inning speech, though, we also experience his genuine, if half-baked, stab at full-frontal disclosure.  It’s no wonder that Lipsky bristles, nor that he, along with this narrative, eventually retreats to a worshipful regret. The magnitude of Wallace’s desire to connect is undeniable.

It’s no wonder that Lipsky bristles, nor that he, along with this narrative, eventually retreats to a worshipful regret. The magnitude of Wallace’s desire to connect is undeniable.

As a portrait, “The End of the Tour,” though expertly edited and shot, doesn’t necessarily succeed more than Lipsky’s aborted magazine profile; its ambivalence reads as less nuanced than mealy-mouthed. But as a glimpse into the uneasy ménage à trois of narcissism, ambition, and loneliness, this film offers sneaky rewards. We can feel Wallace lumbering toward what turned out to be a temporary release from these mortal coils. (He committed suicide twelve years later.) We also can’t help rooting for him.

This was originally published in Word and Film.