I am sitting on the expanse of my friend’s yellowed, crackly Hamptons lawn. It is a meadow, really, and its overripeness is not unappealing. It is comforting, a scent and sign of a summer well-lived. As my own summer was not, I cannot help admiring such wear and tear.

I am sitting on the expanse of my friend’s yellowed, crackly Hamptons lawn. It is a meadow, really, and its overripeness is not unappealing. It is comforting, a scent and sign of a summer well-lived. As my own summer was not, I cannot help admiring such wear and tear.

And yet: I am here now. This friend, who has worked for everything she has, listened to me say, with more than a little self-pity, that I needed a break but could not afford one. Then, rather than murmur the platitudes most offer when confronted with others’ hardships, she did something practical and immensely kind. (The most immense kindnesses are always of a practical nature, I find.) She took a key off her ring and handed it to me. “I will be out of town for the next few weeks,” she said. “Stay in my house while I am gone.”

I write this as a different woman than I have been in ages. I am filled with sea and gently waving trees and the sweet smell of bees and sun and soil doing very good work. Yesterday morning I rode out on a train crowded with rude young people glued to their electronic devices and barely disguised containers of booze, and I wondered if I had made a mistake by abandoning my permakitten for a region for which I had many mocking nicknames. (The HampTonys, The Cramptons, The Peter Framptons.) I told myself: You can return home Monday. But within a few hours of my arrival, I was postponing everything I’d scheduled for the first half of September and shaking my head. How could I have forgotten about this golden early fall? For beneath the brassy balls of this region pulses a very ancient and very forgiving natural grace that I’ve worshipped ever since I first visited 15 years ago.

I’ve been blocking out too much. Too many places, too many people, too many emotions. Too many spiritual homes.

Upon getting settled, I found a bike and rode through country roads, filling my bag with farm-stand and yard-sale booty. I watched the sun descend over an emptying beach after jumping in its great, crashing waves, and took a decadently long, hot shower—the sort that cleans away salt rather than urban grime.  My hair wrapped in a towel turban, my body in a mumu, I padded around the kitchen, assembling a salad of lobster meat and fresh greens and cucumbers and herbs, and hummed along with the crickets outside. I swayed on my friend’s porch swing and ate my salad and drank some wine. I watched the indigo of the sky fade to black, and listened to the silence that was actually wonderfully noisy. Wind whooshing, trees rustling, birds making their points in many octaves. I thought of how my friend had described herself as a “silence worshipper,” and liked her even more.

My hair wrapped in a towel turban, my body in a mumu, I padded around the kitchen, assembling a salad of lobster meat and fresh greens and cucumbers and herbs, and hummed along with the crickets outside. I swayed on my friend’s porch swing and ate my salad and drank some wine. I watched the indigo of the sky fade to black, and listened to the silence that was actually wonderfully noisy. Wind whooshing, trees rustling, birds making their points in many octaves. I thought of how my friend had described herself as a “silence worshipper,” and liked her even more.

Then I climbed into her very big bed, and laughed at my nunlike discomposure. (Ever a cat, I sleep best in areas that barely contain me.) Before I knew it, I was fast asleep.

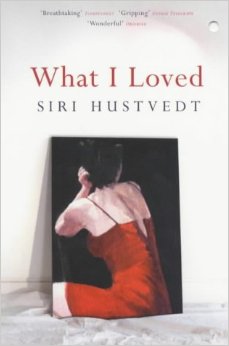

Today I woke full of good intentions about Making Goals and Working on My Book. (Such Germanic capitalization feels necessary.) Instead, I went on another long bike ride and took another long shower. Afterward, I pulled from my friend’s shelves Siri Hustvedt’s What I Loved, which I’d read and loved a decade before. Immediately I began to reread it—drink it, really, since it is that rare piece of literature which is as pleasurable as it is challenging. Its catalogue of the delight and deceit of human intimacy proved even more beautiful than I’d remembered, and I settled into its heavy, painterly stillness– perfect in the unfussy luxury of my friend’s home (all divans and small lamps and good art and soaring windows). With a start, I remembered that this book was key to how she and I had become friends in the first place. She had shared a detail from her life that had reminded me of it, and the next time I saw her, I remembered to bring a copy. She had seen in it what I had seen, and in turn we had felt seen by each other.

But not too seen. Perhaps the respectful boundaries that she and I keep–necessitated by the decades that loom between us, by the circumstances in which we met–help us to maintain that spark. A quote from the book speaks to this phenomenon:

I’ve always thought that love thrives on a certain kind of distance, that it requires an awed separateness to continue. Without that necessary remove, the physical minutiae of the other person grows ugly in its magnification.

I’ve always thought that love thrives on a certain kind of distance, that it requires an awed separateness to continue. Without that necessary remove, the physical minutiae of the other person grows ugly in its magnification.

Today, I will finish rereading it; I am already three-quarters finished, and have only put it down to write to you. As I type, I also am listening to Erik Satie, whose small piano lines are weaving another layer into this soft, whispery quiet holding me close. Somehow it all feels part of this story, as well as the story it may help me create. Art and nature, nature and art. We need both to absorb the joy inherent in every living cell. We need each other to make the connections that come next.