If last month’s “Truth” sings a swan song for the nobility of the media, “Spotlight,” about the Boston Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning exposure of the widespread pedophilia and subsequent cover-ups within the Catholic Church, reminds us that good journalism is not only necessary but possible. It does this by, pardon the pun, practicing what it preaches, and the result is a profoundly satisfying film – perhaps the most satisfying film that American cinema will deliver this year.

If last month’s “Truth” sings a swan song for the nobility of the media, “Spotlight,” about the Boston Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning exposure of the widespread pedophilia and subsequent cover-ups within the Catholic Church, reminds us that good journalism is not only necessary but possible. It does this by, pardon the pun, practicing what it preaches, and the result is a profoundly satisfying film – perhaps the most satisfying film that American cinema will deliver this year.

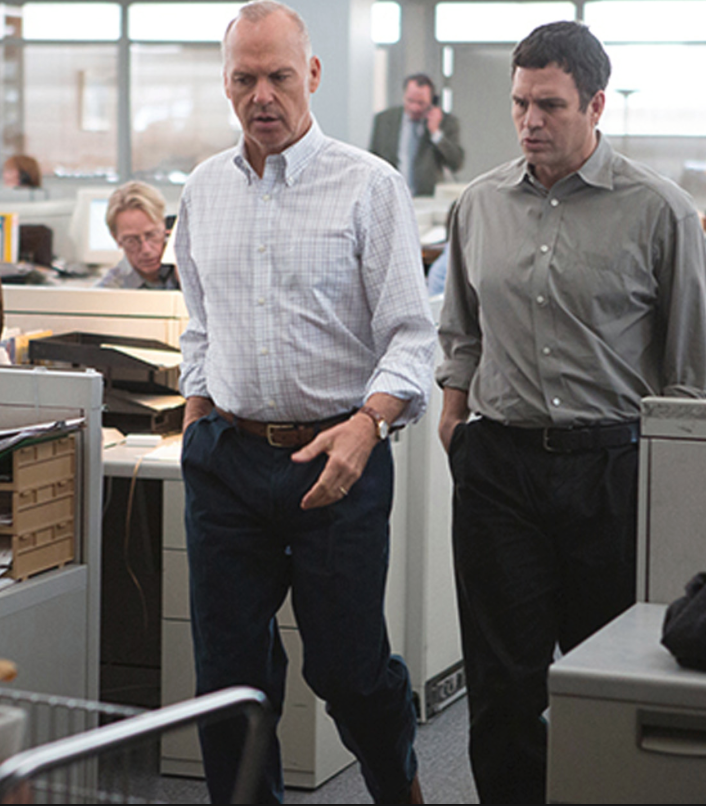

Keeping up the good form he introduced in last year’s “Birdman,” Michael Keaton stars as Walter “Robby” Robinson, a Boston native who is the editor of Spotlight, an investigative arm of the Boston Globe that’s comprised of Michael Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo), Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams), and Matt Carroll (Brian d’Arcy James). All four are lapsed Catholics with Boston roots, which would be neither here nor there had Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber) not just been appointed as the paper’s new editor. It is the summer of 2001, and The Boston Globe has recently been purchased by The New York Times. Baron, a transplant from Florida who is the first Jew ever to hold the position, is a true outsider and is treated accordingly – not only because of professional concerns (he cut staff by fifteen percent at his previous paper) but because Bostonians are, fundamentally, territorial pissers. (To be clear, I am and always will be a proud Masshole.) Almost immediately upon his appointment, Baron commissions a resistant Spotlight crew to take another look at rumors of cover-ups of priestly abuse. As it turns out, he’s right to do so, and the reporters are soon knee-deep in the story.

The genius of “Spotlight” is its fundamentally mild tone. Just when you steel yourself for big opposition, a trap door is revealed through careful digging, which is the way all the best social change has ever been implemented, particularly by news reporters. We get a kinder, gentler Schreiber as Marty, for example, which makes his behind-the-scenes bullshit detector even more effective. Carroll tracks down unnamed, unpunished perpetrators by methodically examining the Church’s records of priests who are sent to treatment centers before reassignment. McAdams, the one woman prominently featured in this story, is in good-girl mode as she interviews victims and questions the priests’ lawyers who have turned “child abuse into a cottage industry,” to quote Robinson. Ruffalo is the one real ham sandwich here. He plays up Rezendes’s aggressive  nerdiness with a lack of nuance that is unusual for the actor but works as he goes after sealed Church documents and prods at Mitchell Garabedian (a bewigged, lock-jawed Stanley Tucci), the mad-dog lawyer who’s representing plaintiffs against the now-defrocked John Geoghan, who molested more than eighty young boys during his priesthood.

nerdiness with a lack of nuance that is unusual for the actor but works as he goes after sealed Church documents and prods at Mitchell Garabedian (a bewigged, lock-jawed Stanley Tucci), the mad-dog lawyer who’s representing plaintiffs against the now-defrocked John Geoghan, who molested more than eighty young boys during his priesthood.

Aside from an early flashback to 1976, in which Geoghan is released from a Boston police station to reps for the Archdiocese, priests seldomly are onscreen in “Spotlight.” Nor are their victims. Instead, this film wisely keeps the story local, focusing almost solely on procedure, procedure, procedure – on how these reporters uncloaked international Church corruption in one of the most Catholic and insular communities in the United States. On how David can still take down Goliath.

Even if helmer/co-writer Tom McCarthy’s last film, “The Cobbler,” hadn’t been a disaster, “Spotlight” would stand out as his greatest work. Pacing and lenswork (aided by director of photography Masanobu Takayanagi) are unfussy and unhurried; backdrops subtly highlight the class differences that define Massachusetts culture; and the crackerjack cast turns in wonderfully unobtrusive performances. John Slattery stands out as too-defended deputy managing editor Ben Bradlee Jr., whose Washington Post editor father was featured in “All the President’s Men” (its influence reigns supreme here), and Billy Crudup mines his smarmy good looks to chillingly strong effect as an attorney for the bad guys.

But the true stand-out is the story itself, and McCarthy wisely ensures this is so, painting a picture of systemic corruption and abuse that is miraculously, usefully bald. For once, Boston culture – its cronyism, its codes of silence and loyalty, its fierce provincialism – is not fetishized so much as put under a microscope, and the result spells out the dark side of tribalism with a clarity that is rarely achieved anywhere. If it’s amazing that this newspaper story ever saw the light of day, it is even more amazing that a Hollywood film could do it justice.

But the true stand-out is the story itself, and McCarthy wisely ensures this is so, painting a picture of systemic corruption and abuse that is miraculously, usefully bald. For once, Boston culture – its cronyism, its codes of silence and loyalty, its fierce provincialism – is not fetishized so much as put under a microscope, and the result spells out the dark side of tribalism with a clarity that is rarely achieved anywhere. If it’s amazing that this newspaper story ever saw the light of day, it is even more amazing that a Hollywood film could do it justice.

This was originally published in Word and Film.