“Anomalisa” may be the most meta-narcissistic movie ever written by Charlie Kaufman, which is saying a lot given that he also wrote “Adaptation,” “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” and “Synecdoche, New York.” It also is not necessarily a slam. Like Lars von Trier, Kaufman has an uncanny ability to globalize his solipsistic sadness with such psychogenic flair that he makes us believe nihilism is a legitimate form of creation. It’s the ultimate inversion of the old hippie phrase “think global, act local,” and, against all odds, it usually works. Alas, it only sort of does in this catalogue of depersonalization masquerading as a love story – perhaps because its subtext reads as supertext in a way that doesn’t stimulate the senses so much as bum them out.

“Anomalisa” may be the most meta-narcissistic movie ever written by Charlie Kaufman, which is saying a lot given that he also wrote “Adaptation,” “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” and “Synecdoche, New York.” It also is not necessarily a slam. Like Lars von Trier, Kaufman has an uncanny ability to globalize his solipsistic sadness with such psychogenic flair that he makes us believe nihilism is a legitimate form of creation. It’s the ultimate inversion of the old hippie phrase “think global, act local,” and, against all odds, it usually works. Alas, it only sort of does in this catalogue of depersonalization masquerading as a love story – perhaps because its subtext reads as supertext in a way that doesn’t stimulate the senses so much as bum them out.

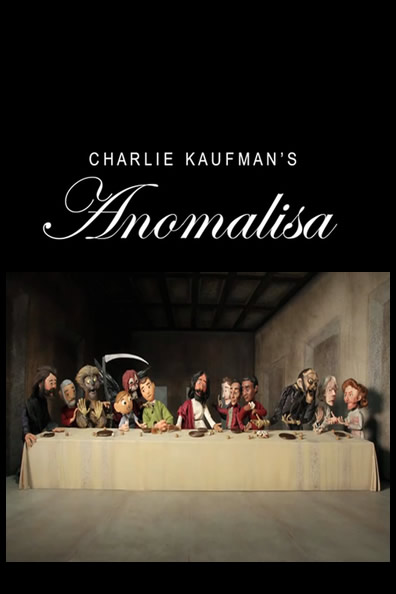

A puppet animation about Michael Stone (David Thewlis), a British inspirational speaker on a one-day business trip to Ohio, “Anomalisa” was funded by Kickstarter (special thanks are given to 1,070 names in the credits) after beginning life as a one-act “radio play” performed in New York and Los Angeles by seated actors reading from scripts.  It was originally written by Kaufman as Franco Fregoli, which is a pseudonym noteworthy for more than its alliteration: The Cincinnati hotel where Stone stays is also called The Fregoli. A simple Google search reveals that a “Fregoli delusion” is a paranoid disorder in which the sufferer believes that different people are actually a single persecutor who assumes a range of appearances.

It was originally written by Kaufman as Franco Fregoli, which is a pseudonym noteworthy for more than its alliteration: The Cincinnati hotel where Stone stays is also called The Fregoli. A simple Google search reveals that a “Fregoli delusion” is a paranoid disorder in which the sufferer believes that different people are actually a single persecutor who assumes a range of appearances.

This makes sense, for while Stone is voiced by actor David Thewlis, nearly everyone else in this film is voiced, with very little modulation, by Tom Noonan, a character actor distinguished most (and most oxymoronically) by his creepily generic quality. What’s more, the animation deployed here (Kaufman co-directs with stop-motion specialist Duke Johnson) renders everyone as marionette dolls of sorts, with seams cut across their markedly similar faces and bodies.

Call this a case of “just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not after you,” because from the first frames of this film, it’s clear that Stone (whose features do not resemble the others) views all of the human race as homogenously un-genius; in conversations with his flight seatmates, a taxi driver, and the hotel employees, he exudes a barely repressed irritation as they prattle on.  Alone in his generic hotel room, he calls his wife, who complains about her PMS while he swills antidepressants and martinis, and a local ex-girlfriend, who’s more rattled than pleased to hear from him. A subsequent meeting with her in a hotel bar goes badly, and after she stalks off, he staggers to his room, where he thrashes unhappily in a too-hot shower. (His lumpy body looks alarmingly realistic.)

Alone in his generic hotel room, he calls his wife, who complains about her PMS while he swills antidepressants and martinis, and a local ex-girlfriend, who’s more rattled than pleased to hear from him. A subsequent meeting with her in a hotel bar goes badly, and after she stalks off, he staggers to his room, where he thrashes unhappily in a too-hot shower. (His lumpy body looks alarmingly realistic.)

Then he hears a voice unlike all the others drifting down the corridor. It is that of Lisa (get the wordplay of the title now?), a baked goods company service rep with a facial scar and a bottomless well of insecurity voiced by Jennifer Jason Leigh. (Between this and “The Hateful Eight,” she’s having quite a year making oddbot appearances in auteurs’ pet projects.) The two spend the night together – insert some disturbingly graphic puppet sex here – and she regales him with badly sung Cyndi Lauper tunes that are magic to his ears because her voice is so one-of-a-kind. Or is it? The minute she makes herself available to him, he falls down a rabbit hole of dissociation and fear in a hot-and-cold cycle that will feel painfully familiar to anyone unfortunate enough to be seduced by the lavish attentions of a narcissist. (Though the female characters are shrill and dumb here, any sexism at hand is just the square to the rectangle of an overall misanthropy.)

All of Charlie Kaufman’s projects toe the line between depression and narcissism but this one lumbers over that line, with a heaviness that’s underscored by the pudgy limbs of this army of Claymation-style figures. It’s a creative device, for what could better depict the isolation and despair of a person who experiences only himself as unique? It’s also a bit of a one-trick ouroboros since these monotonic aesthetics too accurately reflect their subject. “I liked ‘Anhedonia’ better when Von Trier and Woody Allen made it,” said a friend upon exiting the screening. It was a flip comment but I knew what she meant: At least in “Melancholia,” “Annie Hall” (whose original title actually was “Anhedonia”), and Kaufman’s previous films, the protagonists’ inner worlds were so charismatically projected that you understood why they preferred themselves. This time around, that navel proves a gloomy place to dwell for ninety minutes. Where’s your “Eternal Sunshine” when we need it, o Charlie K.?

This was originally published in Word and Film.