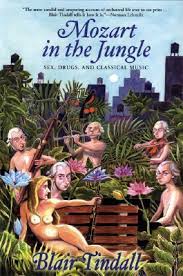

The second season of “Mozart in the Jungle,” the series adapted from classical oboist Blair Tindall’s 2005 memoir, was launched by Amazon Prime right before New Year’s Eve. I hesitate to use the word “dumping” but it’s safe to say most TV shows are usually on hiatus during that time for good reasons. (The multiplexes dangle plenty of Oscar bait for those keen to escape family time.) So the two Golden Globes – best TV comedy and best TV comedy actor for Gael García Bernal – that the show just won probably surprised more than the people who’ve never watched it. (My social media feed was clotted with tweets like “Guess I need to start watching #MITJ now? #whoknew.”) A colleague familiar with my appreciation for the show messaged me: “Can you pretend to defend this as the best TV comedy?”

The second season of “Mozart in the Jungle,” the series adapted from classical oboist Blair Tindall’s 2005 memoir, was launched by Amazon Prime right before New Year’s Eve. I hesitate to use the word “dumping” but it’s safe to say most TV shows are usually on hiatus during that time for good reasons. (The multiplexes dangle plenty of Oscar bait for those keen to escape family time.) So the two Golden Globes – best TV comedy and best TV comedy actor for Gael García Bernal – that the show just won probably surprised more than the people who’ve never watched it. (My social media feed was clotted with tweets like “Guess I need to start watching #MITJ now? #whoknew.”) A colleague familiar with my appreciation for the show messaged me: “Can you pretend to defend this as the best TV comedy?”

My answer, actually, was no. In fact, I’m not even sure if “Mozart” qualifies as a comedy (though certainly it’s funnier than “The Martian,” which inexplicably won the Golden Globe for best film comedy). That said, I do believe it delivers exactly what we should expect from premium television: a glimpse into a typically unexplored subculture, truths about the human condition, and high and low pleasure.

Ironically, both sorts of pleasure emanate from one person – the extremely toothsome Bernal, who richly deserves his award. He plays Rodrigo, the wild-child orchestra conductor loosely based on Gustavo Dudamel, the music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and it’s a role that would have grated if Bernal didn’t bring such surefooted sweetness to his mad-genius mania. The other protagonist is Hailey (pronounced “Jai Alai” by Rodrigo), a fresh-faced oboist who is equally well portrayed by Lola Kirke.  In season one, Rodrigo had just been appointed the leader of the fictional New York Symphony, and in turn had appointed Hailey as his assistant after she proved herself not yet polished enough for orchestra inclusion. Sparks flew between them but the focus was kept on world-building – on spelling out the modern infrastructure of one of the world’s oldest artistic traditions, from the classical instrumentalists to the wealthy donors who keep them afloat. This season finds the show more confident, as is Hailey herself, who has been promoted to second chair oboe. Done with the business of explaining itself, MITJ is free to revel in the important things: passion, money, and art.

In season one, Rodrigo had just been appointed the leader of the fictional New York Symphony, and in turn had appointed Hailey as his assistant after she proved herself not yet polished enough for orchestra inclusion. Sparks flew between them but the focus was kept on world-building – on spelling out the modern infrastructure of one of the world’s oldest artistic traditions, from the classical instrumentalists to the wealthy donors who keep them afloat. This season finds the show more confident, as is Hailey herself, who has been promoted to second chair oboe. Done with the business of explaining itself, MITJ is free to revel in the important things: passion, money, and art.

Many feel “Transparent,” that other acclaimed Amazon Prime offering, more richly deserved last Sunday’s accolades. Though I greatly admire that series’ gentle-hearted exploration of gender, sexuality, and family, there’s no point in using it to rain on MITJ’s parade. In fact, in its depiction of how commerce both curtails and enables art, the latter does an unusually good job at tackling the topic of class (the one area in which “Transparent” can fall short). Exhibit A: Part of Rodrigo’s charm is a flagrant unwillingness to toe a corporate line, yet we’re made to see how this leaves others to clean up the orchestra’s financial messes. We also watch how the musicians suffer financially even as they hobnob with one-percenters. This season zeroes in on the symphony’s continuing contract negotiations, in which the instrumentalists are being strong-armed by financiers who hire assistants just to fetch them nuts at parties (a true detail). This all could get rather bleak if everything weren’t so elegantly sexualized – not to put too fine a point on it. (There I go again.)

Everybody but everybody jumps into bed with each other (which is also true in Tindall’s book) and for the most part they’re so pretty we’re glad to watch. Take Saffron Burrows, she of the endless cheekbones and limbs, who plays Cynthia, the cellist heading the musicians’ negotiating committee. Last season she was the paramour of former maestro Thomas (Malcolm McDowell, the Platonic essence of a “silver fox”) but this season finds her in bed with labor lawyer Gretchen Mol (who’s unusually comfortable in her skin here). This is but one of the myriad subplots stuffed into each episode’s twenty-five minutes in lieu of a central storyline.

Everybody but everybody jumps into bed with each other (which is also true in Tindall’s book) and for the most part they’re so pretty we’re glad to watch. Take Saffron Burrows, she of the endless cheekbones and limbs, who plays Cynthia, the cellist heading the musicians’ negotiating committee. Last season she was the paramour of former maestro Thomas (Malcolm McDowell, the Platonic essence of a “silver fox”) but this season finds her in bed with labor lawyer Gretchen Mol (who’s unusually comfortable in her skin here). This is but one of the myriad subplots stuffed into each episode’s twenty-five minutes in lieu of a central storyline.

For the most part, this lack of forward momentum is okay because co-creators Paul Weitz, Jason Schwartzman, and Roman Coppola so patently adore their subject. The latter two are cousins, of course, whose grandfather was a celebrated composer and conductor (you may also have heard of their family members Francis and Sofia); they make good use of their heritage in painting the mise-en-scène of this loving, high-strung musical clan. A few storylines falter: A South American trip delves into some ethnic stereotypes that should have been seized at customs, and a mini-caper in which the orchestra’s concertmaster fakes the theft of his violin for insurance money feels forced. Best is the season’s new emphasis on Ladies Liberty – the double passions of women who are more consumed by what they do than who they do. Hailey dumps her wet noodle of a dancer beau but also struggles to get out from under Rodrigo’s shadow. Even her tension with frenemy mentor Betty (Debra Monk) is equitably rendered as we’re shown the older woman’s sacrifices and struggles as well.

I’m saving the best for last, though. As board chair Gloria, the great Bernadette Peters shines as a beacon of self-possession. In season one, her character waffled between being a bad-ass and simply bad; now she’s not just more sympathetic but also more sensual. Though this season doesn’t boast the standout soundtrack you’d expect from a series about music, it does give Peters some much-deserved time in front of a cabaret microphone. It’s hard to argue that her shimmying as she husks “Come On-a My House” advances the plot in any tangible way but that’s part of the true appeal of this show. A grand concerto it may not be, but as a collage of stolen moments – an etude, maybe, or a gavotte – it offers more than its fair share of insights and well-heeled glamor.

I’m saving the best for last, though. As board chair Gloria, the great Bernadette Peters shines as a beacon of self-possession. In season one, her character waffled between being a bad-ass and simply bad; now she’s not just more sympathetic but also more sensual. Though this season doesn’t boast the standout soundtrack you’d expect from a series about music, it does give Peters some much-deserved time in front of a cabaret microphone. It’s hard to argue that her shimmying as she husks “Come On-a My House” advances the plot in any tangible way but that’s part of the true appeal of this show. A grand concerto it may not be, but as a collage of stolen moments – an etude, maybe, or a gavotte – it offers more than its fair share of insights and well-heeled glamor.

This was originally published in Word and Film.