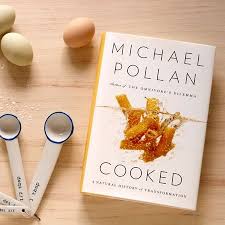

“Cooked,” Michael Pollan’s new four-part Netflix docuseries about cooking past and present, features Pollan the historian, Pollan the sociologist, Pollan the aspiring chef, and, yes, Pollan the wrangler. He may not be wagging his finger at us as emphatically as he often does (see: The Omnivore’s Dilemma, “Food Inc.”) but the journalist can’t help but shame us about our terrible habits regarding the industry, preparation, and consumption of food. Though entertainingly educational and far gentler than his usual treatises, this is not a show to watch while eating. This is a show to watch while cooking – preferably from scratch.

“Cooked,” Michael Pollan’s new four-part Netflix docuseries about cooking past and present, features Pollan the historian, Pollan the sociologist, Pollan the aspiring chef, and, yes, Pollan the wrangler. He may not be wagging his finger at us as emphatically as he often does (see: The Omnivore’s Dilemma, “Food Inc.”) but the journalist can’t help but shame us about our terrible habits regarding the industry, preparation, and consumption of food. Though entertainingly educational and far gentler than his usual treatises, this is not a show to watch while eating. This is a show to watch while cooking – preferably from scratch.

As our own cooking efforts dwindle – Pollan estimates that the average American spends twenty-seven minutes a day on food preparation, which is less than half the time spent in 1962 – the amount of hours we log watching food television and cinema is on a major uptick. On one hand, the reason hardly requires spelling out: Who doesn’t love deliciousness? But the real reasons may be closer to the bottomless hunger we feel when eating Wonder Bread. Having stripped the wheat of its original nutrition, we crave the kind of nourishment that no amount of “enrichment” can confer. Though modern life has made it possible and even pragmatic for us to eat meals we have not prepared ourselves, we benefit emotionally, physically, and spiritually from cooking in ways that continue to haunt us. Some have attempted to rectify this void by taking part in the slow-food movement. But many more have developed the habit of eating supermarket rotisserie chickens and Trader Joe’s tikka masala while watching others cook on TV and in movies.

Pollan theorizes that, since animals can’t cook and gods love sacrifice, fire is a happy medium for our species. I have a theory that the flickering of screens subconsciously sates the desire for the flickering of the hearth that once centered clans. There’s a human need to spend time around a fire – to be soothed and mesmerized by its light, warmth, and transformation of raw materials into something safe for our consumption. Having lost that collective experience – and most households don’t even have working fireplaces anymore – we watch our phones, tablets, and televisions instead. Is it any wonder, then, that we gravitate toward watching others cook? Unconsciously, we’re approximating that hearth experience as closely we can.

In modern life, media is the closest many of us come to community. Once upon a time, cooking provided that community since it connected us to food traditions passed down from generation to generation as well as to the people around us. It was also how we connected to an ethos of cheerful survival – to literally making lemonade out of lemons. It wasn’t until family units became nuclear rather than extended – when “normal” Western households shrunk to just parents and children – that the movement to industrialize food and get ladies out from behind the stove really took root. Women were dying to get out of the kitchen because, for the first time in history, they were alone in there. Yet because as a culture we never learned to embrace the domestic activities that traditionally had been codified as feminine – nurturing, sewing, and, yes, cooking – our lives became lonelier and, ultimately, less complete, with the corresponding empty calories of commercially prepared cuisine. Here in our brave new world, we sate that mostly unacknowledged longing for constructive, communal coziness by watching cooking alone together, to paraphrase film critic Roger Ebert.

But I’m ignoring the elephant in the room. The real reason for the rising appeal of food TV and film is the element of pleasure. The more we watch rather than act, the more we unconsciously long for the visceral, the tactile, the sensual. Preparing food connects us to our bodies and desire in a way that merely eating does not, perhaps because our senses are more fully stimulated when we experience the gestalt of food – the bright purple of sliced plums, the satisfying squish of ripe tomatoes, the oddly sexy aroma of melted butter – before consuming it. And if we’re not actually cooking, watching others do so may be the next best thing. Not to mention that nobody likes to see themselves as passive consumers, and watching others prepare food feels proactive, even if we’re doing it while mawing frozen pizza. We’re not cooking tonight, we whisper to ourselves, but eventually we might.

But I’m ignoring the elephant in the room. The real reason for the rising appeal of food TV and film is the element of pleasure. The more we watch rather than act, the more we unconsciously long for the visceral, the tactile, the sensual. Preparing food connects us to our bodies and desire in a way that merely eating does not, perhaps because our senses are more fully stimulated when we experience the gestalt of food – the bright purple of sliced plums, the satisfying squish of ripe tomatoes, the oddly sexy aroma of melted butter – before consuming it. And if we’re not actually cooking, watching others do so may be the next best thing. Not to mention that nobody likes to see themselves as passive consumers, and watching others prepare food feels proactive, even if we’re doing it while mawing frozen pizza. We’re not cooking tonight, we whisper to ourselves, but eventually we might.

This was originally published at Signature.