J.G. Ballard, whose 1975 British novel High-Rise has been adapted into a film opening this month in the United States, could be described as one of the preeminent twentieth-century writers of “weird fiction” – a term spawned by H. P. Lovecraft to describe his own work and the work of other writers he liked. They are tales, as David Tompkins has written, “not necessarily supernatural in intent but ones that aim to create a sense of dread, awe, terror, and the like.” Perfect fodder for film, in other words, especially in an era in which apocalyptic cinema is the name of the game in multiplexes and arthouses alike.

J.G. Ballard, whose 1975 British novel High-Rise has been adapted into a film opening this month in the United States, could be described as one of the preeminent twentieth-century writers of “weird fiction” – a term spawned by H. P. Lovecraft to describe his own work and the work of other writers he liked. They are tales, as David Tompkins has written, “not necessarily supernatural in intent but ones that aim to create a sense of dread, awe, terror, and the like.” Perfect fodder for film, in other words, especially in an era in which apocalyptic cinema is the name of the game in multiplexes and arthouses alike.

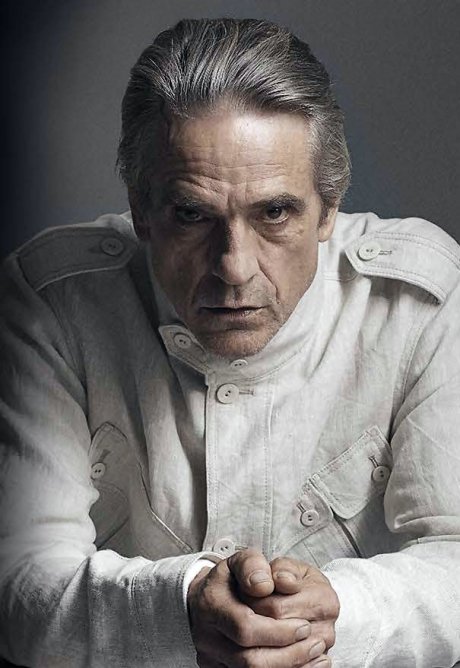

As point of fact, in many ways “High-Rise” is a better film than it is a book, which is not a statement I have many occasions to deliver. It stars Tom Hiddleston as Robert Laing, a recently divorced doctor who moves into a vast luxury condo tower and immediately succumbs to its Bacchanalian glamour. Set in 1980 (1975’s slight future, to hijack Spike Jonze’s handy phrase), it begins at the end, when Laing is in high caveman dudgeon, barbecuing a dog and squatting in the feral pit that was once his swinging pad, his sharp suit in bloody tatters. Then it zips back three months, when the building still looms as a modish palace, complete with its own supermarket, liquor stores, pools, and Louis XIV-style penthouse where architect Anthony Royal (Jeremy Irons) presides like a benevolent god and an icy king. As the new bachelor on the block, Laing is a sought-after number: One female resident purrs that his tenancy application is “very Byronic”; another describes him as “the best amenity in the building.” Soon enough he finds himself bopping through any number of shindigs – all paisley fabrics and lingering glances and suddenly bared breasts – that make key parties look like Shaker gatherings.

Here is where director Ben Wheatley – the puckish shit-stirrer responsible for “Kill List,” “Sightseers,” and a fistful of “Dr. Who” episodes – really takes advantage of the visual twists offered by his medium. A chaste dinner date in the book morphs into a zipless fuck in the film, without changing any of the dialogue. Hence single mother Charlotte (Sienna Miller) murmurs lines like “I only like talking about myself,” and “You know, there’s a brothel in building,” as Laing throws her gleaming long legs behind her ears and gives it to her good. That’s just the beginning of a choreography through the inner workings of the building that suggests the collaboration of Kubrick and Altman, if either of them had ever been able to work with anyone else. A social satire above all else, this “High-Rise” is a microcosmic society in which poorer families crowd onto the lower floors, mid-level professionals like accountants and dentists crowd the mid-level floors, and Richie Riches lounge among the clouds. Indeed, when earth mother Helen Wilder (Elisabeth Moss) dares express her upwardly mobile aspirations to her deadbeat doc-maker husband, Richard (Luke Evans), they are wonderfully literal: “Maybe we can move to a higher floor,” she murmurs, pawing at her pregnant belly and puffing on a Silk-Cut.

Oh, I just love the casting of this film. It’s such a pleasure to see Moss back in period mode after the string of WTF indies she’s stumbled through since the finale of “Mad Men.” She’s hilarious in pinstriped overalls, sipping small glasses of chardonnay and swaying among her flock of already conceived children. “That’s not how you spell arse, darling,” she remarks absently when one of her terrors carves ARSS into a wooden table. As heartless, wanton Charlotte, Miller finally makes good use of that shellacked prettiness that filmmakers usually misapply, and Hiddleston, w ho’s always channeled equal parts menace and melancholy in his too-bright eyes (he was the perfect vampire in “Only Lovers Left Alive”), is just right as a Lord of the Fly-by here, especially when he runs amok. Even Irons, clad in the white and beige of the “someone else will clean this up” very wealthy, seems hardier and more prepossessing than ever in his fallow youth.

ho’s always channeled equal parts menace and melancholy in his too-bright eyes (he was the perfect vampire in “Only Lovers Left Alive”), is just right as a Lord of the Fly-by here, especially when he runs amok. Even Irons, clad in the white and beige of the “someone else will clean this up” very wealthy, seems hardier and more prepossessing than ever in his fallow youth.

But the real headline is how this concrete ecosystem falls off the rails. We see how dangerously self-contained the building becomes as neighborly in-fighting devolves into full-blown class war. Yet because we glide from group scene to group scene without ever landing, we float above the cacophony in a montage of gorgeous dissolution that eventually descends into a fog of boredom–at least for us. A perfect martini hardens into mold, surfaces gleam with a rainbow of uppers and downers, and we’re hypnotized by the peculiar beauty rather than repulsed – even when a cocktail party slides into a shag-carpeted orgy and then again into a demonic ritual with bloodshed galore. Rendered in the plummy tones of a nineteenth-century oil painting and fashioned like all the Grimm Fairy Tales at once (women literally wear capes, hoods, Bo Peep-puffed sleeves, and plenty of red and white velvet), it’s like watching a Renoir panting morph into one by Hieronymus Bosch. While he still has the wherewithal to occasionally leave it, Laing describes his new home as “prone to fits of mania, narcissism, and power failure,” but that neurotica speedily devolves into a murderous sociopathy that is utility-free. “He’s raping women he’s not supposed to!” roars one penthouse denizen when a lackey revolts. By then, we’re not necessarily invested enough to care, let alone be scandalized.

What’s the takeaway exactly? Watching (and reading) this story, it seems no surprise that its author served time in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. Wheatley honors Ballard’s dystopian vision – a “Pandora’s box whose thousand lids were one by one inwardly opening” – with a glee that is dizzyingly infectious. Oh, how flimsy is the roof on our modern civilization.

This was originally published at Signature.