Whit Stillman is not exactly a literary adaptation sort. From “Metropolitan,” his 1990 directorial debut, he has worked from arch screenplays of his own devise – wholly original amalgams of doctoral theses, oddly formal courtships, and high-low banter. In fact, he may be one of the only helmers on the block who has written novels based on his own films; I especially like his Barcelona and Metropolitan: Tales of Two Cities.

Whit Stillman is not exactly a literary adaptation sort. From “Metropolitan,” his 1990 directorial debut, he has worked from arch screenplays of his own devise – wholly original amalgams of doctoral theses, oddly formal courtships, and high-low banter. In fact, he may be one of the only helmers on the block who has written novels based on his own films; I especially like his Barcelona and Metropolitan: Tales of Two Cities.

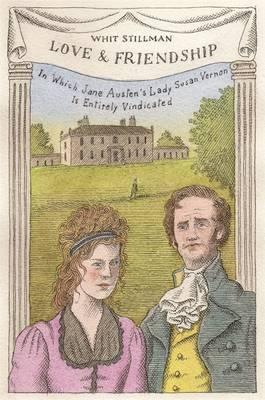

But Jane Austen has always threaded through his films. In “Metropolitan” especially, her influence is laid bare; in it, fuddy-duddy Manhattan debutantes gravely discuss Pride & Prejudice in lieu of their feelings for each other. Now in “Love & Friendship,” he’s called his own bluff by adapting Lady Austen or, rather, Lady Susan, the eighteenth-century author’s first and least beloved effort. Lest Stillman seem impertinent for renaming it, Austen never named her novella in the first place, and this new title almost seems an endeavor to grant Susan the status of her other books. Still, it’s toothless, the one off note of this otherwise very pleasurable film.

Perhaps it’d be best entitled “Marriage & Manners,” since, like all of Austen’s and Stillman’s work, it is as much a study of economic and social status as it is a romantic comedy of errors. In fact, it’d probably be best (if inelegantly) titled “Money & Mean Girls,” for it is the one story in which Austen reveals her considerable fangs. About Lady Susan Vernon, an underfunded, comely widow of some years and some notoriety, this book faltered not only because of its epistolary form – not Austen’s forte, as it turned out – but because Susan was Austen’s one true anti-heroine, and the author neglected to build out any supporting characters worthy of Susan’s Machiavellian machinations.

A champion of self-rationalizing charismatics, Stillman is the right white knight to rescue Austen from herself in this case. He casts a purple-clad Kate Beckinsale as Susan, and it’s a dream match of actress and material;  not since his “Last Days of Disco” has she so fully leaned into the clever cruelty lurking beneath her peaches-and-cream complexion. Here she’s paired again with “Disco” costar Chloe Sevigny, who plays Susan’s accomplice, Alicia Johnson, and seems vaguely uncomfortable with this late-eighteenth-century banter. Abandoning the epistolary form almost entirely, Stillman fleshes out the book’s best lines with many good ones of his own, adding droll title cards and plot flourishes crafted from subtexts that Austen uncharacteristically made barely “sub.”

not since his “Last Days of Disco” has she so fully leaned into the clever cruelty lurking beneath her peaches-and-cream complexion. Here she’s paired again with “Disco” costar Chloe Sevigny, who plays Susan’s accomplice, Alicia Johnson, and seems vaguely uncomfortable with this late-eighteenth-century banter. Abandoning the epistolary form almost entirely, Stillman fleshes out the book’s best lines with many good ones of his own, adding droll title cards and plot flourishes crafted from subtexts that Austen uncharacteristically made barely “sub.”

Susan has recently arrived at Churchill, the estate of her late husband’s un-cunning brother Charles Vernon (Justin Edwards). His wife, Catherine (Emma Greenwall, shining in a somewhat thankless role), is rightfully suspicious of Susan, who arrives in a cloud of ill-repute for canoodling with the eminently dashing, eminently married Manwaring (Lochlann O’Mearáin). Though Mrs. Vernon maintains a pretense of civility, her bias is baldly inherited by her brother, Sir Reginald DeCourcy (Xavier Samuel). Out of a bored malice and a financial imperative, Susan seduces this dishy young man while keeping Manwaring on the side and attempting to pair the wealthy dimwit Sir James Martin (Tom Bennett) with daughter Frederica (Morfydd Clark), who, in her namby-pamby way, protests the match, as she’s sweet on DeCourcy. Unhampered by such conventions as a conscience and maternal devotion, Susan adeptly steamrolls everyone’s objections to her scheming, whose existence she airily denies. Only to Alicia does she reveal her true intentions, and she does so with a delicious nastiness that’s more Oscar Wilde than Elizabeth Bennett. (“My dear Alicia,” she says. “What a mistake were you guilty of in marrying a man too old to be agreeable and too young to die.”)

It’s an awful lot to track, but Stillman keeps it all afloat in a froth of quick wit and beautiful costumes and cinematography. Shot in Ireland, this period film looks better than many with ten times its budget, and Benjamin Esdraffo’s score is admirably free of the swelling violins that doom those prestige dramas. Also not in evidence: the self-congratulatory camp that doomed “Damsels in Distress,” Stillman’s last effort. Instead, “Love & Friendship” restores the Austen edges that history – and her own later efforts – have largely erased. Not for nothing, but hundreds of years later, the unapologetically self-possessed Susan is the type of middle-aged woman who is still lamentably scarce in cinema and literature.

It’s an awful lot to track, but Stillman keeps it all afloat in a froth of quick wit and beautiful costumes and cinematography. Shot in Ireland, this period film looks better than many with ten times its budget, and Benjamin Esdraffo’s score is admirably free of the swelling violins that doom those prestige dramas. Also not in evidence: the self-congratulatory camp that doomed “Damsels in Distress,” Stillman’s last effort. Instead, “Love & Friendship” restores the Austen edges that history – and her own later efforts – have largely erased. Not for nothing, but hundreds of years later, the unapologetically self-possessed Susan is the type of middle-aged woman who is still lamentably scarce in cinema and literature.

This was originally published on Signature.