Mention breakout 1980s novelists, and the names Bret Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney inevitably top the list. But back in the day, Tama Janowitz was easily as big a deal as either of those boys. Witty where they were edgy, she set her comedies of errors among the rubble of Alphabet City and the rarified air of Upper East Side townhouses, and she lampooned the rites and rituals of the creative class with a rouge-tipped mischief that recalled the love child of Edith Wharton and Dorothy Parker – if either had been the type to wear Godzilla earrings.

Mention breakout 1980s novelists, and the names Bret Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney inevitably top the list. But back in the day, Tama Janowitz was easily as big a deal as either of those boys. Witty where they were edgy, she set her comedies of errors among the rubble of Alphabet City and the rarified air of Upper East Side townhouses, and she lampooned the rites and rituals of the creative class with a rouge-tipped mischief that recalled the love child of Edith Wharton and Dorothy Parker – if either had been the type to wear Godzilla earrings.

More than any other writer of the 1980s, Janowitz captured the true zeitgeist of that decade in which the spirit of the 1960s finally loosened its hold on America. Conservatism and capitalism were on the rise, gentrification was the name of the game, and “alternative” scenes were suddenly more about aesthetics – music, fashion, pop art, blackened catfish, and hair (oh my god, hair) – than ideology. In irresistible detail, Janowitz poked at the incongruities of this world we were to inherit: the $10,000 fake-fur coats people wore while not making rent; the punk-rock peacocks famous solely for their desire to be famous. It took “A Room with a View” director James Ivory to notice she was, at heart, a period dramatist – and a bourgeois one at that.

To date, she is best known for “Slaves of New York,”  that 1986 collection of inter-connected short stories about a set of downtown New York painters, sculptors and designers, and the people who fuck and finance them. It is her most gloriously absurdist effort, and if it is moderately anti-feminist – a less-successful passage savages a radically “humor-ectimized” women’s studies professor – its portrait of money and mating is ruthlessly accurate. Beneath its pink mohawks and oil paintings of Daffy Duck, “Slaves” is true to its title: an interrogation of not remotely free love. It was the most clever death knoll for the 1960s anyone could have written.

that 1986 collection of inter-connected short stories about a set of downtown New York painters, sculptors and designers, and the people who fuck and finance them. It is her most gloriously absurdist effort, and if it is moderately anti-feminist – a less-successful passage savages a radically “humor-ectimized” women’s studies professor – its portrait of money and mating is ruthlessly accurate. Beneath its pink mohawks and oil paintings of Daffy Duck, “Slaves” is true to its title: an interrogation of not remotely free love. It was the most clever death knoll for the 1960s anyone could have written.

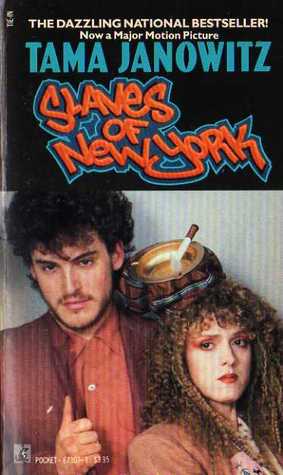

Janowitz wrote a screenplay of her flagship book for Andy Warhol to direct, but when he died unexpectedly in 1987, Ivory took the reins. Given his penchant for mise-en-scène, his involvement was not entirely a surprise, though the Bowery was a far cry from the tea tables and gardens where his protagonists usually lounged. The resulting 1989 film – a romantic comedy centering on aspiring hat designer Eleanor (Bernadette Peters), shacked up with up-and-coming painter Stash (Adam Coleman Howard) – received a tepid response at best. “It’s unwise to wear an ashtray on your head unless you’re certain you have more personality than the prop,” snarled New York Times critic Janet Maslin in what was a thoroughly typical review.

Viewed twenty-seven years later, the film is a far more instructive time capsule than “Bright Lights, Big City” and “Less Than Zero,” the other big literary adaptations of those 1980s literary whiz kids.  In a refreshing reversal of the ageism of Hollywood, fortysomething Peters, already a Broadway megastar, was technically too old to play twenty-seven-year-old Eleanor but Ivory said she was the only woman for the part. He was right: With her soft indignance and Cherubin curves, she was the perfect foil for the razor-sharp milieu of “Slaves” – an eternally wistful Betty Boop strapped into a leather dress. Then-twenty-one-year-old Howard, sporting a mullet and a sulky machismo, was another well-cast example of Ivory’s anti-ageism: Stash was thirtysomething in the book. At best, this young man treats Eleanor like a balmy hausfraus – What do I hate most about you? he demands. Your insecurity? Your messiness? – but she can’t leave since housing is so expensive and she earns so little.

In a refreshing reversal of the ageism of Hollywood, fortysomething Peters, already a Broadway megastar, was technically too old to play twenty-seven-year-old Eleanor but Ivory said she was the only woman for the part. He was right: With her soft indignance and Cherubin curves, she was the perfect foil for the razor-sharp milieu of “Slaves” – an eternally wistful Betty Boop strapped into a leather dress. Then-twenty-one-year-old Howard, sporting a mullet and a sulky machismo, was another well-cast example of Ivory’s anti-ageism: Stash was thirtysomething in the book. At best, this young man treats Eleanor like a balmy hausfraus – What do I hate most about you? he demands. Your insecurity? Your messiness? – but she can’t leave since housing is so expensive and she earns so little.

In a seminal scene, Eleanor’s friend (played by a Janowitz eclipsed by enormous hair and earrings)  announces her intent to move to New York to live with a guy she only tolerates so she can meet someone better. Eleanor advises her against it. “There’re hundreds of women here,” she says. “They are out on the prowl. And all the men are gay or slaves themselves.”

announces her intent to move to New York to live with a guy she only tolerates so she can meet someone better. Eleanor advises her against it. “There’re hundreds of women here,” she says. “They are out on the prowl. And all the men are gay or slaves themselves.”

It’s a terribly bald statement, and the fact that it’s delivered by a Minnie Mouse who wobbles on neon-green Louis XIV heels and wears hats made of garbage only underscores the film’s stark assessment of capitalism run amok in bohemia. Stash and his colleagues are too competitive to be actual pals – they circle each other warily at openings, nouveau diners, and baseball fields while their vinyl-clad girlfriends hiss like asps at the ball – but that makes sense, given that they’re grown children who don’t know how to play nicely at the sandbox. The real grownups here are the ones who make cash – gallerists Ginger (Mary Beth Hurt with a bright asymmetrical bob) and Victor (Chris Sarandon, best remembered as Susan’s first husband), kazillionaire Chuck (John Harkins) and designer Wilfredo (a young and surprisingly toothsome Steve Buscemi), the only financially successful artist of the lot. Eventually, Wilfredo commissions Eleanor to make hats for a fashion show, and she lands her own apartment and slave, pretty boy Jan (Michael Schoeffling, emblazoned in the memory of ‘80s girls everywhere as dreamboat Jake in “16 Candles”).

The narrative arc of this film – girl loves boy, girl breaks up with boy, girl finds better boy – may be more conventional than its literary antecedent but the visuals compensate by a mile. If Jonathan Demme (“Something Wild”) or Jim Jarmusch (“Down by Law”) might have better captured the East Village’s edges, Ivory was the right fop to spotlight how  mercenary counterculture had already become; it even seems right that the film is guilty of the same compromises it catalogues. Every scene is a loving homage to the Raggedy Ann and Andy Warhols of that era – the safety-pinned, fluorescent feathers that comprised the street uniform of this let-’em-eat-cupcake, neon-kitsch wonderland. I watch it now and laugh: I viewed the clothes as so normal at the time. What’s funnier: Our country has never been so wildly creative again. It was the beginning of the end and the end of the beginning, and I’m so glad we had sweetly dimpled Peters Pan as our new-wave Cassandra.

mercenary counterculture had already become; it even seems right that the film is guilty of the same compromises it catalogues. Every scene is a loving homage to the Raggedy Ann and Andy Warhols of that era – the safety-pinned, fluorescent feathers that comprised the street uniform of this let-’em-eat-cupcake, neon-kitsch wonderland. I watch it now and laugh: I viewed the clothes as so normal at the time. What’s funnier: Our country has never been so wildly creative again. It was the beginning of the end and the end of the beginning, and I’m so glad we had sweetly dimpled Peters Pan as our new-wave Cassandra.

This was originally published on Signature.