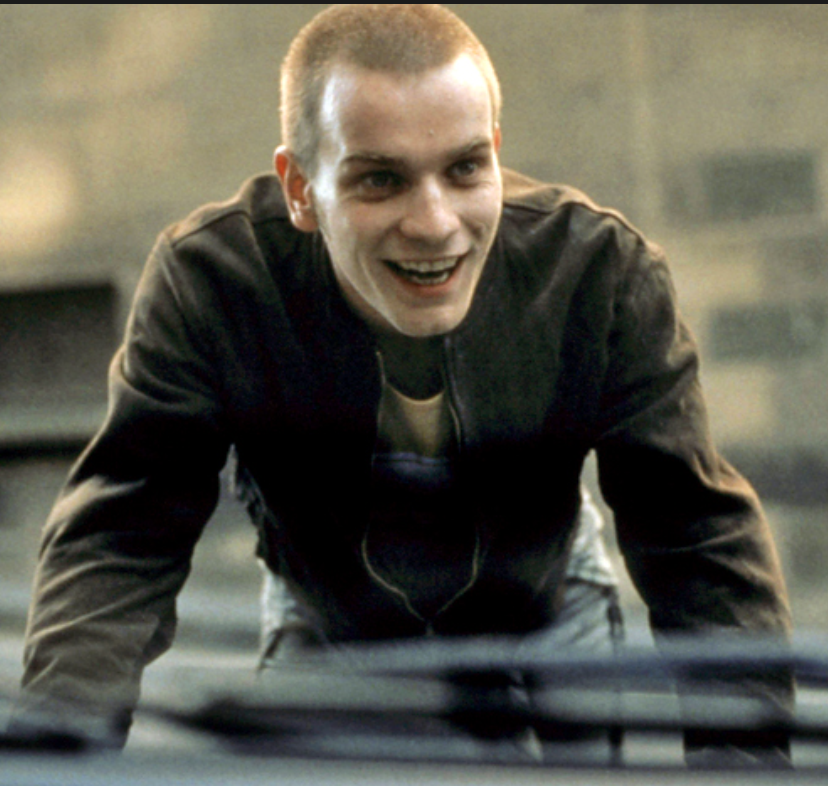

It begins with the throbbing drums of Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life” and a handful of strung-out, wild-eyed lads racing down a city street. Then Ewan McGregor – white-faced, teeth bared – hurls his emaciated frame in front of a cop car and begins a voiceover that sounds like a commercial for Satan himself: “Choose life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fuckin’ big television ….” He keeps going, ire building – “Choose sitting on that couch watching mind-numbing, spirit-crushing game shows, stuffing fucking junk food into your mouth. Choose rotting away at the end of it all, pissing your last in a miserable home, nothing more than an embarrassment to the selfish, fucked-up brats you spawned to replace yourselves. Choose your future.” A montage of these boys shooting junk flies before us in a fugue of ecstasy. “Choose life … But why would I want to do a thing like that? I chose not to choose life. I chose somethin’ else. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who needs reasons when you’ve got heroin.”

It begins with the throbbing drums of Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life” and a handful of strung-out, wild-eyed lads racing down a city street. Then Ewan McGregor – white-faced, teeth bared – hurls his emaciated frame in front of a cop car and begins a voiceover that sounds like a commercial for Satan himself: “Choose life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fuckin’ big television ….” He keeps going, ire building – “Choose sitting on that couch watching mind-numbing, spirit-crushing game shows, stuffing fucking junk food into your mouth. Choose rotting away at the end of it all, pissing your last in a miserable home, nothing more than an embarrassment to the selfish, fucked-up brats you spawned to replace yourselves. Choose your future.” A montage of these boys shooting junk flies before us in a fugue of ecstasy. “Choose life … But why would I want to do a thing like that? I chose not to choose life. I chose somethin’ else. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who needs reasons when you’ve got heroin.”

Those are the first minutes of “Trainspotting,” Danny Boyle’s ear-splitting, cornea-burning 1996 adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s eponymous 1993 Scottish novel and, with all respect to Quentin Tarantino, it was the best film prologue we 1990s kids had ever seen. If Tom Cruise had Renee Zellweger “at hello” in that decade’s “Jerry Maguire,” Ewan McGregor had the rest of us with his deeply ironic “Choose life.” It spoke volumes – zines, really – about the high-octane aimlessness of a generation that was post-punk, post-hippie, post-Nixon, post-Reagan, post-Thatcher, pre-Internet, and very, very pre-AIDS cocktail. The prologue – the whole film – spoke for all of us who’d just graduated school to enter a world where there were no jobs and sex equaled death. That 1980s pop anthem no longer applied: The future was not bright. We did not need shades.

Though I rarely strayed from a routine of sunrise yoga and macrobiotic meals, I’d felt an uncomfortable solidarity with Welsh’s rabid, staccato novel, and Boyle’s adaptation, which every twentysomething I knew breathlessly anticipated, was both more and less than we’d hoped it would be. It featured more dance music and old-school tracks (Velvet Underground, Iggy) than the grunge presiding stateside at the time; more tight jeans and belly-baring tees than the baggy thrift-store finds in which we were hiding. Such quibbles may sound superficial – or maybe they don’t, given that young people now identify themselves by their aesthetic preferences even more than we did. But as we were looking anywhere and everywhere for an accurate catalogue of our despair, those stylistic discrepancies loomed large. (What’s weird: Those Scottish hipsters more closely resembled today’s Williamsburg denizens.)

Though I rarely strayed from a routine of sunrise yoga and macrobiotic meals, I’d felt an uncomfortable solidarity with Welsh’s rabid, staccato novel, and Boyle’s adaptation, which every twentysomething I knew breathlessly anticipated, was both more and less than we’d hoped it would be. It featured more dance music and old-school tracks (Velvet Underground, Iggy) than the grunge presiding stateside at the time; more tight jeans and belly-baring tees than the baggy thrift-store finds in which we were hiding. Such quibbles may sound superficial – or maybe they don’t, given that young people now identify themselves by their aesthetic preferences even more than we did. But as we were looking anywhere and everywhere for an accurate catalogue of our despair, those stylistic discrepancies loomed large. (What’s weird: Those Scottish hipsters more closely resembled today’s Williamsburg denizens.)

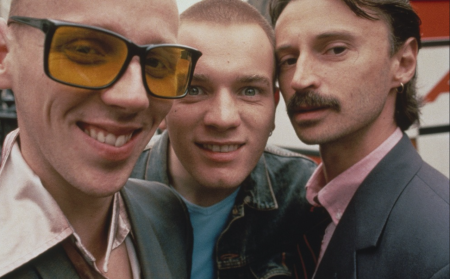

The film also jarred because of its unilaterally unlikeable characters. McGregor starred as Mark Renton, aka Rent Boy, an unreliable if brutally honest narrator who tended to report on himself in a third-person burr. He was skinny, short, and perpetually clad in gray jeans outlining a surprisingly impressive package – the sort of nasty sod who looked like he was wearing braces even when he was not. Renton lived off his parents, the dole, small-time robberies, and other drug users in his environs: cancer patients, senior citizens, and mothers with mothers’ little helpers. He also wasn’t above screwing over his friends as he was certain they’d do the same to him. Among those ranks: Sick Boy, the seemingly soulless Sean Connery fiend played with a shock of platinum hair and an obscenely protuberant red tongue by Jonny Lee Miller; Spud, the hapless dimwit played with impeccable timing by Ewan Bremner; rage-aholic, tiny-limbed Begbie (Robert Carlyle, a far cry from “The Full Monty”); and Tommy (Kevin McKidd of “Grey’s Anatomy”), the footie-loving Johnny-Come-Lately whose bad luck becomes gargantuan in the hands of Rent Boy.  The ladies were few and far between but in possession of the film’s best lines: a still-apple-cheeked Shirley Henderson hissing, “I expect a thoughtful lover; failure on your part to live up to these very reasonable expectations will result in swift resumption of a non-sex situation”; an under-aged Kelly Macdonald sneering at her cigarette and Rent Boy, to whom she purrs: “You’re a quiet sensitive type but, if I’m prepared to take a chance, I might just get to know the inner you: witty, adventurous, passionate, loving, loyal. Taxi!”

The ladies were few and far between but in possession of the film’s best lines: a still-apple-cheeked Shirley Henderson hissing, “I expect a thoughtful lover; failure on your part to live up to these very reasonable expectations will result in swift resumption of a non-sex situation”; an under-aged Kelly Macdonald sneering at her cigarette and Rent Boy, to whom she purrs: “You’re a quiet sensitive type but, if I’m prepared to take a chance, I might just get to know the inner you: witty, adventurous, passionate, loving, loyal. Taxi!”

The film was nothing if not stylish, and to date that remains its chief strength and weakness. With unflagging editing, it zipped along with Rent Boy’s trips on and off the wagon – ducking into blandly lit respectability, dipping back into the shit-stained drug dens and pool halls where these mates skulked, unconvinced of the redeeming value of, well, anything. If we didn’t feel anything for them, this seemed right; they didn’t feel anything, period. The film ended predictably: with death, with thievery, with betrayal, and with a pickup of Rent Boy’s fangs-bared “choose life” monologue. In short, it was perfectly of a piece – a brilliant, sticky homage to Generation X.

The critic David Edelstein has dubbed Boyle “our greatest living shallow director.” While that’s not far off, it means Boyle was the ideal documentarian of the world’s first post-substance generation. We nineties kids were an interstitial group of humans if ever the twentieth century produced one: close enough to the sixties to know what we were missing, not yet equipped with the high technology of busy-boredom that has kept subsequent generations from shrieking, “What’s it all about, Alfie?” In lieu of organic smoothies and  premium binge-watching, we had junk food and junk TV; in lieu of the instant connections afforded by social media and smartphones, we had long-distance phone bills and longer silences. Was it better? Creatively, maybe, but all you have to do is revisit this film – and Boyle and Welsh reportedly are, as a “Trainspotting 2” is in the works – and you can see the most mournful of ad jingles was my generation’s swan song: Rinse. Lather. Repeat.

premium binge-watching, we had junk food and junk TV; in lieu of the instant connections afforded by social media and smartphones, we had long-distance phone bills and longer silences. Was it better? Creatively, maybe, but all you have to do is revisit this film – and Boyle and Welsh reportedly are, as a “Trainspotting 2” is in the works – and you can see the most mournful of ad jingles was my generation’s swan song: Rinse. Lather. Repeat.

This was originally published at Signature.