Tom Tykwer swears he doesn’t “just walk around reading books in hopes of finding new material.” Given the director’s screenwriting chops (“Run Lola Run,” “3”), it seems a legitimate claim, and yet he does possess a knack for literary adaptations. In his takes on everything from David Mitchell’s millennium-spawning meta-novel “Cloud Atlas” to Patrick Süskind’s period-film explosion “Perfume,” Tykwer has managed to adapt what has largely been considered unfit for screen. (No less than Stanley Kubrick declared “Perfume” unadaptable.) Most recently he has tackled A Hologram for the King, Dave Eggers’s post-financial crisis novel about an American businessman adrift in a Mideast desert. As fish-out-of-water as tales ever go, it’s a surprisingly pleasurable effort that suggests Tykwer may be cinema’s new adaptation king – though he still lurks relatively under the radar.

Tom Tykwer swears he doesn’t “just walk around reading books in hopes of finding new material.” Given the director’s screenwriting chops (“Run Lola Run,” “3”), it seems a legitimate claim, and yet he does possess a knack for literary adaptations. In his takes on everything from David Mitchell’s millennium-spawning meta-novel “Cloud Atlas” to Patrick Süskind’s period-film explosion “Perfume,” Tykwer has managed to adapt what has largely been considered unfit for screen. (No less than Stanley Kubrick declared “Perfume” unadaptable.) Most recently he has tackled A Hologram for the King, Dave Eggers’s post-financial crisis novel about an American businessman adrift in a Mideast desert. As fish-out-of-water as tales ever go, it’s a surprisingly pleasurable effort that suggests Tykwer may be cinema’s new adaptation king – though he still lurks relatively under the radar.

The fifty-year-old German is a quadruple threat, for starters. In addition to working as a screenwriter and director, he’s a producer of some repute and the co-composer of nearly all his films’ scores. His debut feature was “Die tödliche Maria,” the well-received 1993 German-language adaptation of Christiane Voss’s book – both of which are now nearly impossible to obtain in English translation. But Tykwer made his first mega-splash with his third directorial effort, “Run Lola Run.” Hyperkinetic, hyperbolic, and throbbing with techno-tribal rhythms, split screens, fast and slow motion, jump cuts, whip pans, still photographs, animation, and shifts between color and black-and-white film and video, the 1999 race-the-clock thriller was a shock-rock of German existential cinema with a splatter of titular lead Frankie Potenta’s strawberry-dyed hair to match. Not since “Pulp Fiction” had anything so enlivened art-house cinema.

It was hard to imagine how Tykwer could follow up that breakout, but he managed it by abruptly shifting gears and directing the grave (sometimes too grave) “Heaven.” Though in its own way as sinewy as “Lola,” this Italian- and English-language escape drama was decidedly linear, even sere, with powerful visuals and performances from Cate Blanchett and Giovanni Ribisi. Only the story – half-baked and, alas, half-hearted – fell short. From that, Tykwer seemingly learned a lesson; since then, he’s only directed his own original screenplays or ones adapted from great literature.

It was hard to imagine how Tykwer could follow up that breakout, but he managed it by abruptly shifting gears and directing the grave (sometimes too grave) “Heaven.” Though in its own way as sinewy as “Lola,” this Italian- and English-language escape drama was decidedly linear, even sere, with powerful visuals and performances from Cate Blanchett and Giovanni Ribisi. Only the story – half-baked and, alas, half-hearted – fell short. From that, Tykwer seemingly learned a lesson; since then, he’s only directed his own original screenplays or ones adapted from great literature.

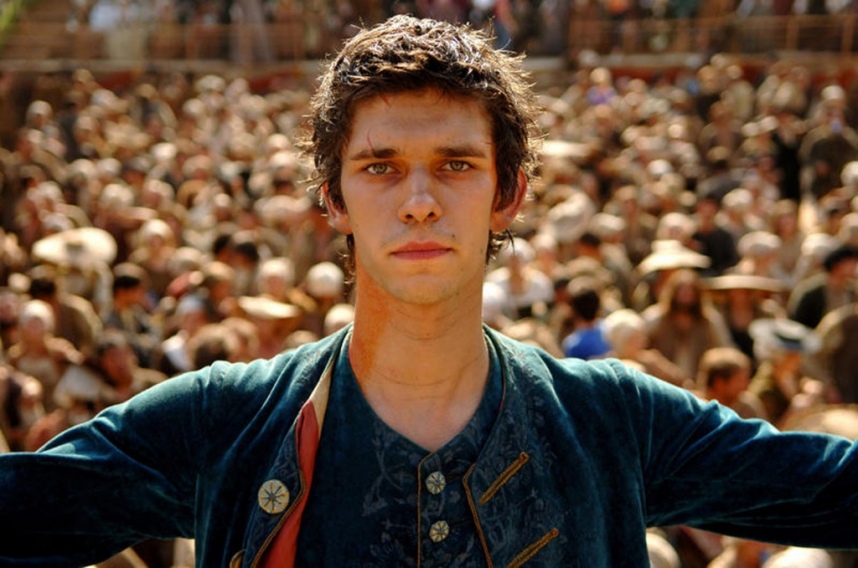

The first among these adaptations was “Perfume: The Story of a Murderer,” a teeming study in eighteenth-century magical realism featuring wily Ben Whishaw as a perfumer so intent on achieving the perfect scent that he’d kill to obtain it. Forget 3-D; the film’s Hieronymus Bosch-level chaos was a fourth-dimensional assault on audience’s senses – a superlative union of method and material, if ever there were one. Like “3,” the Berlin-set, Tykwer-conceived account of a fortysomething heterosexual couple who takes on a younger male lover, it was an oddbot film that reflected an audience of the slight future – presuming that future was more utopian than dystopian.

“Cloud Atlas,” that sci-fi study of reincarnation, was mostly scoffed at by critics and audiences upon its 2014 release. But though its shoddy makeup and acting seem dogged by the curse of co-directors The Wachowskis, its rhapsodically rendered themes of freedom from such binaries as race, gender, class, and even linear time are Tykwer through and through. Though he may be one of the flashiest directors around, his flash always contains a transcendence that is anything but superficial. “I’m trying to really relate to our inner experiences when I conceive visuals,” he has said to Slant Magazine. “And a movie that doesn’t confront us with drastic imagery doesn’t represent life.” He has also said: “The major aspect of being able to attach myself to material, or write it, is that I have a really substantial subjective force that I identify with. I’m not just fascinated by the framing or the surface, the general appeal of something.”

This leads us to “Hologram.” It is a quieter and more contained film than most of Tykwer’s efforts, which is ironic given that its subject – an American businessman attempting to sell new technology to Saudi Arabian royalty – seems the stuff of Ishtar-level bedlam. Focusing more on the universality of middle-age disappointment than international politics, this  rueful comedy stars Tom Hanks as the businessman in question and Sarita Choudhury as his doctor, and draws upon Tykwer’s nonsequential editing and wide pans gently, so gently – the way two tired lovers might caress each other late in the day and late in life. Like all of the director’s films, “Hologram” has been quizzically received, but I believe it introduces a new chapter of his output – one in which life has grown so complex that we must surrender to it fully. He has said: “I know what it means to wake up one morning aware that your life is no longer carrying you away from birth but rather towards death.”

rueful comedy stars Tom Hanks as the businessman in question and Sarita Choudhury as his doctor, and draws upon Tykwer’s nonsequential editing and wide pans gently, so gently – the way two tired lovers might caress each other late in the day and late in life. Like all of the director’s films, “Hologram” has been quizzically received, but I believe it introduces a new chapter of his output – one in which life has grown so complex that we must surrender to it fully. He has said: “I know what it means to wake up one morning aware that your life is no longer carrying you away from birth but rather towards death.”

For now, Tykwer, never one to shy from any artistic medium, seems to be trying his hand at television. Having directed some episodes of The Wachowski Siblings’ Netflix show, “Sense-8,” he’s now spearheading “Babylon Berlin,” a German TV series adapted from Volker Kutscher’s books about a police inspector in 1920s Berlin. I can imagine him cinematically tackling more literature in the future – ideally a book by Margaret Atwood. Her unblinking marriage of science and spirit would suit him well.

This was originally published on Signature.