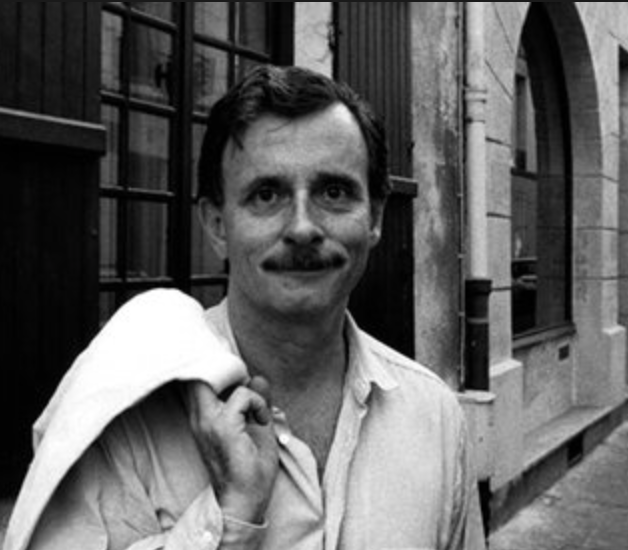

In the wake of the Orlando murders and during LGBT pride month, I have been looking to the elders of the literary queer community for wisdom and context. I’ve been reading lesbian poet, essayist, and self-proclaimed woman warrior Audre Lorde. I’ve been reading gay essayist and novelist James Baldwin. And I’ve been reading the words of gay essayist, cultural critic, playwright, biographer, memoirist, and novelist Edmund White. Still very much on the scene – Our Young Man, his latest novel, was released only this spring – he might protest being called an elder, despite his seventy-six years. Yet as a participant at Stonewall, as the co-founder of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and as the co-author of the groundbreaking tome Joy of Gay Sex, White deserves esteemed elder status. He also deserves it because he is one of our country’s best living writers.

In the wake of the Orlando murders and during LGBT pride month, I have been looking to the elders of the literary queer community for wisdom and context. I’ve been reading lesbian poet, essayist, and self-proclaimed woman warrior Audre Lorde. I’ve been reading gay essayist and novelist James Baldwin. And I’ve been reading the words of gay essayist, cultural critic, playwright, biographer, memoirist, and novelist Edmund White. Still very much on the scene – Our Young Man, his latest novel, was released only this spring – he might protest being called an elder, despite his seventy-six years. Yet as a participant at Stonewall, as the co-founder of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and as the co-author of the groundbreaking tome Joy of Gay Sex, White deserves esteemed elder status. He also deserves it because he is one of our country’s best living writers.

To say that Edmund White is unrecognized would not be exactly accurate. He has won a National Book Award, the Award for Literature from the National Academy of Arts and Letters, and is the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship. Dave Eggers has called him “one of the three or four most virtuosic living writers of sentences in the English language” and John Irving has named him “one of the best writers of my generation.” Yet White is remarkably under-read given the astonishing quality of his prose. In interviews he always allows that, of the dozens of books he has published, only Joy of Sex has ever made any “real money.”

I’ve often wondered why. It’s not that high-minded literature has fallen wholly out of fashion; witness the success of such writers as Eggers himself. The most obvious – and likely most accurate – reason is White’s subject matter. Out since age twelve, White writes unabashedly about gay sex. The tetralogy of autobiographical novels for which he’s best known – A Boy’s Own Story, The Beautiful Room Is Empty, The Farewell Symphony, and The Married Man – follows an unnamed protagonist from the closeted 1950s through gay liberation to the AIDs crisis. (White was diagnosed as HIV positive in the 1980s but has remained unusually asymptomatic.) Threading through all these stories are Proustian descriptions of the narrator’s erotic exploits and attractions – so Proustian, in fact, that it comes as no surprise that White has penned a biography of that author (as well as of Genet). Edmund is that rare modern writer who seems to benefit from an ecstasy of influence rather than Bloom’s gloomier “anxiety of influence.”

I’ve often wondered why. It’s not that high-minded literature has fallen wholly out of fashion; witness the success of such writers as Eggers himself. The most obvious – and likely most accurate – reason is White’s subject matter. Out since age twelve, White writes unabashedly about gay sex. The tetralogy of autobiographical novels for which he’s best known – A Boy’s Own Story, The Beautiful Room Is Empty, The Farewell Symphony, and The Married Man – follows an unnamed protagonist from the closeted 1950s through gay liberation to the AIDs crisis. (White was diagnosed as HIV positive in the 1980s but has remained unusually asymptomatic.) Threading through all these stories are Proustian descriptions of the narrator’s erotic exploits and attractions – so Proustian, in fact, that it comes as no surprise that White has penned a biography of that author (as well as of Genet). Edmund is that rare modern writer who seems to benefit from an ecstasy of influence rather than Bloom’s gloomier “anxiety of influence.”

Whether he’s regarding a trick’s asshole or an heiress’s updo, White frames his observations with the work of other artists (writers and visual artists, mostly; not so much actors or rock stars). About Stonewall, for example, he has said, “The riot itself seemed more Dada than Bastille, a kind of romp.” His references are so proliferant, in fact, that they’d draw focus from the acuity of his own observations were he a lesser stylist. But because he’s a purist – his hedonism never includes so much as a gratuitous adjective – his enthusiasms only elevate his gay experience to an even higher plane.

He’s never been much for plot (yet another reason he writes few bestsellers) but his books are so ordered that it’s fitting he named one after a symphony. At heart, he is a terrific formalist, which may be why he’s able to glide so adeptly among genres – from historical fiction to essays to creative nonfiction to biography to straight-up reporting. (He wrote for Vogue for ten years.) This combination of lush prose and highly structured narratives de-familiarizes what is familiar to anyone in queer America and introduces it to everyone else,  rendering the orgies of Fire island and West Village bath houses universal, or at least “wondrous strange.”

rendering the orgies of Fire island and West Village bath houses universal, or at least “wondrous strange.”

Some believe everything is about sex, but for White, sex seems to be about everything else. And while he is overt, he is not overtly political, at least in the manner of a Larry Kramer. More, White is concerned with beauty, whose power he never underestimates and whose many forms he democratically worships. “I would say a novelist’s proper job is to be sensitive to the way things look,” he has said. He does that job well. He is my favorite writer to read as a writer, as a reader, as a flaneur, and as a student of the corners of male sexuality that are rarely revealed to women even in bed. White also is my favorite writer to read as a naked sensualist; his impeccable work ethic makes bottoms of us all by enticing us to live inside the power of his pleasure.

In the last decade, Edmund White has suffered a heart attack and a few strokes. He seems to have recovered but if Our Young Man is his last book, its profound exploration of superficiality will be a fitting final note for his career. Kundera wrote of the unbearable lightness of being but White actually channels it. To him, gay liberation means queerness is a philosophy – one in which we can choose rather than inherit our lives, one in which we are led by our delight. Even in sorrow. Even in revolt. With such a beautiful beginner’s mind, White remains our young man no matter how beautifully his wisdom has deepened. We are lucky he has been alive to document our times – so much so that I wonder if future generations will more fully recognize his genius. As he wrote in The Farewell  Symphony:

Symphony:

As Joshua’s words come echoing across the water and down the years to me, I can’t help thinking that his life was not just his finest thoughts about poetry and friendship, expressed in a style that rejected forcefulness in favor of sympathy, but it was also comprised of his long mornings in his dressing gown with his telephone, newspapers, the Hu Kwa smoked tea and the little sterling-silver strainer that sat in its drip cup when it wasn’t straddled across a cup catching leaves. His life was made up of his pleasure in the morning glories as well as his hilarity … After [his death] I looked through all the letters I’d ever received from him and realized I’d been unworthy of him then, that he’d been sending them through time to me as I would become years later.

This originally appeared on Signature.