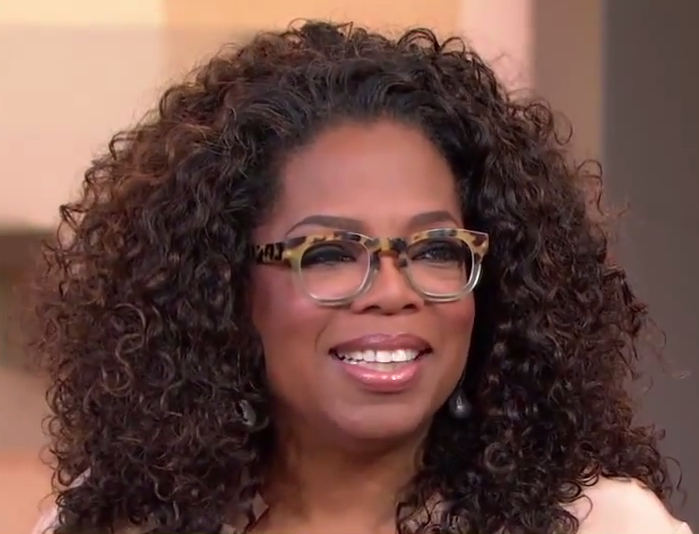

Recently it was announced that Oprah Winfrey plans to executive produce and star in an HBO film adaptation of Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. When I read this news, I caught myself heaving an immense sigh of relief. With Oprah at the helm, I knew Miss Henrietta was going to be safe.

Recently it was announced that Oprah Winfrey plans to executive produce and star in an HBO film adaptation of Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. When I read this news, I caught myself heaving an immense sigh of relief. With Oprah at the helm, I knew Miss Henrietta was going to be safe.

Skloot’s 2010 biography of Henrietta Lacks is one of the most extraordinary literary events of this decade, which only befits the extraordinary Lacks and her legacy. Widely regarded as a lynchpin of her Baltimore neighborhood, she was a beautiful, small African-American woman who said what she thought, fed everyone, and painted her nails perfectly red. Raised by her grandfather in the slave quarters where their family had once been relegated, she shared a room with first cousin David “Day” Lacks, with whom she birthed her first child at age fourteen. Day and she married, moved to Baltimore from the tobacco farms of Virginia, and went on to have four more children, including the developmentally disabled Elsie and her youngest, Deborah.

At thirty years old, Henrietta began to describe a knot in her womb. (I won’t say “complain”; from all reports, Henrietta wasn’t the type to complain.) Though rightfully wary of the medical establishment’s abuse of people of color, she visited the charity ward of Johns Hopkins Hospital, where her symptoms were dismissed as connected to the syphilis that her cheating husband often passed on to her. When she was finally diagnosed with cervical cancer, biopsies of the diseased tissue were taken and cultured without her consent. Then, while the cancer destroyed its host, that tissue took on a life of its own in a lab in the same hospital, becoming the infamous HeLa (named from the first two letters of her first and last names), the first human cells to continuously reproduce themselves. It is likely that the cancer’s aggression – an autopsy of Lacks’s corpse revealed “tumors the size of baseballs that had nearly replaced her kidneys, bladder, ovaries and uterus” and “other organs so covered in small white tumors it looked as if someone had filled her with pearls” – explains the cells’ unprecedented tenacity. By her death at age thirty-one, Henrietta had been eclipsed by HeLa. A lab assistant conducting Lacks’s autopsy is quoted as saying, “When I saw her red toenails, I thought, Oh jeez, she’s a real person.”

HeLa became an internationally celebrated cell line whose samples have been used in some of the most important research in human medicine, including the polio vaccine, chemotherapy, Parkinson’s disease, herpes, cloning, gene mapping, the effects of atomic bombs, and in vitro fertilization. Meanwhile, Henrietta’s other line foundered and she was largely erased from history – to the point that few knew the antecedent name for “HeLa.” Her children were sexually abused and physically assaulted by their guardians; Elsie died in an institution shortly after her mother’s passing; Deborah was haunted by mental and physical disorders, and first-born Lawrence was imprisoned for murder. In short, though Henrietta’s cells could be bought for hundreds of dollars a vial – though they have helped save humankind and have become a billion-dollar enterprise unto themselves – her descendants could not even afford health insurance. The legal, ethical, and spiritual issues of this story encapsulate everything shadowing our country today.

Science journalist Rebecca Skloot enters this tale as a character, not just a narrator, as she attempts to win the family’s trust and restore Lacks to her rightful place in history. A breathlessly paced tale that’s part medical journal, part detective story, and part sociopolitical thriller, it is perhaps best described as creative nonfiction, with novelistic flourishes that give us a better sense of Henrietta, a woman with “walnut eyes and full lips” who liked to dance and took such good care of her community that everyone trooped en mass to Johns Hopkins to donate blood on her behalf–a detail that relays the largesse Henrietta involuntarily extends to the world via her cells.) In short, this is not just Hollywood fodder but Oprah fodder – and the fact that the premium cable goddess is spearheading this project goes a long way toward sidestepping its one danger: that white folks will heap all the credit for saving African Americans from injustices inflicted by white people.

For if there’s a queasiness in the story, it’s that a white woman functions as the legacy savior (Skloot’s book became a New York Times bestseller) and that the African-American vernacular in which characters like Deborah speak is uncomfortable because we know the author is white. This is not entirely Skloot’s fault – she had been obsessed with Henrietta since first encountering her cells in high school and was the only one who stepped up to tell this forgotten story. But in the wrong hands a film adaptation could end up as another story of white swashbucklers and people of color as victims, objects, cartoons.

With Oprah playing the Great Oz as well as fraught Deborah, we have less to fear; witness how much she imparted in her small but pivotal “Selma” role. Also attached to the project is producer Alan Ball, who showed us a thing or two about immortality, death, and family trauma in “Six Feet Under.” And George C. Wolfe is stepping up as screenwriter and director, which is a coup given how he’s honored unacknowledged chapters of African American history in such works as “Bring in Da Noise, Bring in Da Funk” and “Lackawanna Blues.” He’ll nail the sweeping scope, the rush of nonlinear time, the mythological elements, and the necessary awe to do right by this legend. Some animation may even be in order.

So who else should be attached to this project? Ladies man Day should be played by sly-eyed Wood Harris (“The Wire”). George Gey, the biologist who sampled (read: stole) Henrietta’s cells could be Chris Cooper, that good guy who excels at playing the bad guy. Lawrence should be played by Michael B. Jordan, if he’ll consent to a supporting role in the wake of his “Creed” glory; he summons hurt anger better than anyone else working today. Skloot should be Brie Larson, who in “Short Term 12” demonstrated how gracefully she can trip over good intentions. Henrietta herself should be played by sweet-faced Jurnee Smollett-Bell (“Friday Night Lights,” “True Blood”), who has the charisma, heart, and walnut eyes to render Henrietta immortal in yet another medium.

So who else should be attached to this project? Ladies man Day should be played by sly-eyed Wood Harris (“The Wire”). George Gey, the biologist who sampled (read: stole) Henrietta’s cells could be Chris Cooper, that good guy who excels at playing the bad guy. Lawrence should be played by Michael B. Jordan, if he’ll consent to a supporting role in the wake of his “Creed” glory; he summons hurt anger better than anyone else working today. Skloot should be Brie Larson, who in “Short Term 12” demonstrated how gracefully she can trip over good intentions. Henrietta herself should be played by sweet-faced Jurnee Smollett-Bell (“Friday Night Lights,” “True Blood”), who has the charisma, heart, and walnut eyes to render Henrietta immortal in yet another medium.

This was originally published on Signature.