“To Kill a Mockingbird” is mostly upheld for Gregory Peck’s Oscar-winning portrayal of good daddy Atticus Finch, iconically clad in tortoise shell glasses and cream linen suits. But in viewing the adaptation of Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1960 novel today, I am taken aback by its micro-aggression–by the racism it perpetuates and condemns in equal measure.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” is mostly upheld for Gregory Peck’s Oscar-winning portrayal of good daddy Atticus Finch, iconically clad in tortoise shell glasses and cream linen suits. But in viewing the adaptation of Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1960 novel today, I am taken aback by its micro-aggression–by the racism it perpetuates and condemns in equal measure.

It was released at the end of 1962, which was the last year before the cultural upheaval that we associate with the 1960s. In 1963, John F. Kennedy was shot, and America seemed to not only lose its innocence but its self-assurance. The assassinations of Bobby Kennedy, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X followed, as did the Vietnam War and Watergate and, well, you get the picture. “To Kill a Mockingbird” was filmed during America’s last year of post-World War II complacency. For better and worse, you can tell.

Or course, by 1962 the Civil Rights movement was well under way. Brown vs. Board of Education had outlawed public school segregation, and Dr. King had organized innumerable lunch counter sit-ins and bus boycotts. Change was in the air, and one way Hollywood responded was to adapt Lee’s book about small-town lawyer Finch, who defends a black man wrongly accused of raping a white woman. In the fictional town of Maycomb, Alabama, during the Great Depression – when the movement was but a twinkle in freedom fighters’ eyes – Finch was the widowed father of six-year-old Scout (Mary Badham) and ten-year-old Jem (Phillip Alford), raised with the help of black housekeeper Calpurnia (Estelle Evans). An adult Scout provides demurely voiced narration as her younger incarnation mucks about in tomboy attire with effete brainiac Dill (John Megna), who was not-so-loosely based upon Harper Lee’s real-life bestie, Truman Capote.

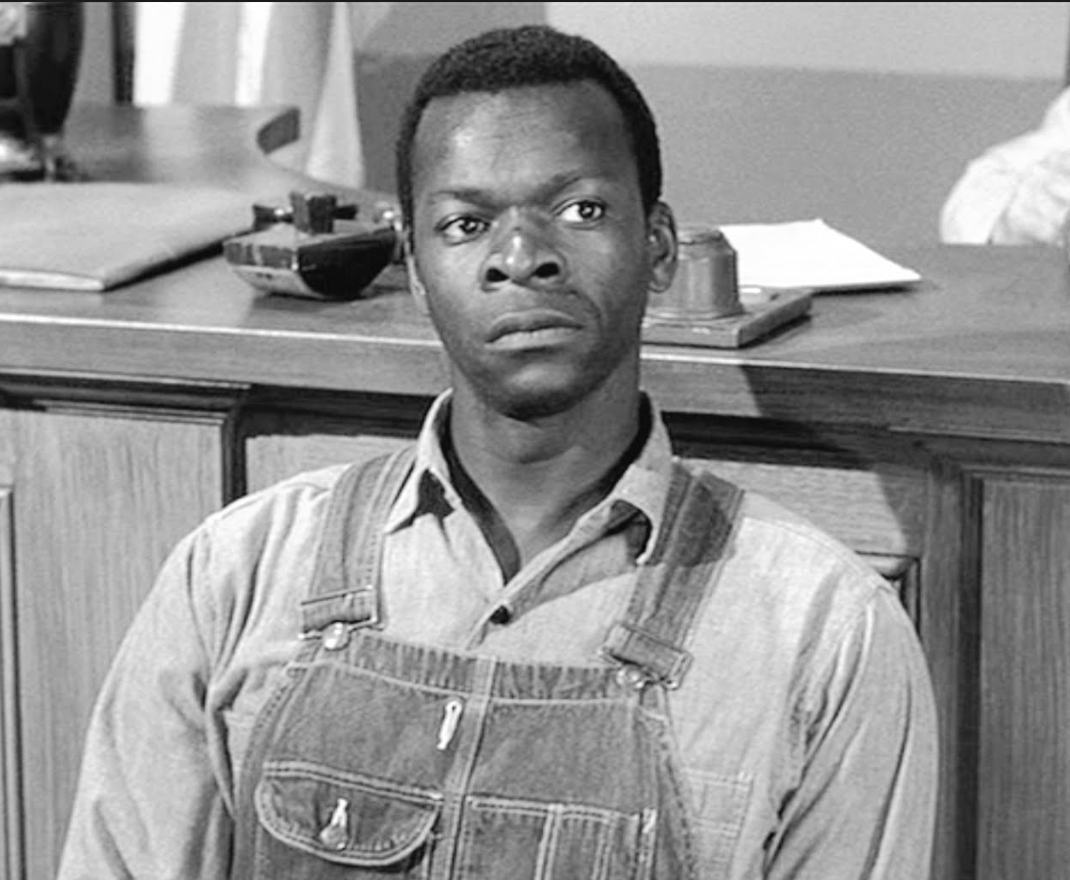

For a while the film takes place on the level of the kids. It’s even shot from their height, which cements our sense of the world from their perspective. When Scout is put to bed by her father, we look up at his lantern jaw with the same awe that she does.  But once Tom Robinson (Brock Peters) has been accused of sexually assaulting Mayella Ewell (Collin Wilcox), the film centers on Finch’s experience while the children are relegated to the peanut gallery – literally, as they watch much of the court proceedings from the “colored section.” The equation of children and people of color is bald.

But once Tom Robinson (Brock Peters) has been accused of sexually assaulting Mayella Ewell (Collin Wilcox), the film centers on Finch’s experience while the children are relegated to the peanut gallery – literally, as they watch much of the court proceedings from the “colored section.” The equation of children and people of color is bald.

To be clear, this equation is not the fault of Lee, who poked at all her characters with the same childlike curiosity. It’s more the doing of director Robert Mulligan, who depersonalized his actors of color by keeping them in wide shots and profiles except when rubber-necking on Robinson’s tears. Screenwriter Horton Foote doesn’t get off scot-free, either. Though Finch gently eschews racial hate words and treats everyone with respect and humanity – though his courtroom defense of Robinson is deservedly legendary – he never questions the cause of the black man’s death, which is obtuse at best. We are told he is killed because he tries to escape, but it is obvious that townspeople have gone vigilante. Finch, less propelled by righteous anger than a distaste for social transgression, never worries himself over such a possibility.

In his 1962 review of the film, Village Voice critic Andrew Sarris wrote, “As usual, the Negro is less a rounded character than a Liberal construct…. Brock Peters tries hard to break through the layers of moral whitewash, but he is finally smothered by Peck’s unctuous nobility…. The plot takes a retributive turn with the redneck who started all the fuss getting his just desert while attempting to murder Peck’s children. Yet one ‘innocent Negro’ and one murderous redneck scarcely cancel each other out.”

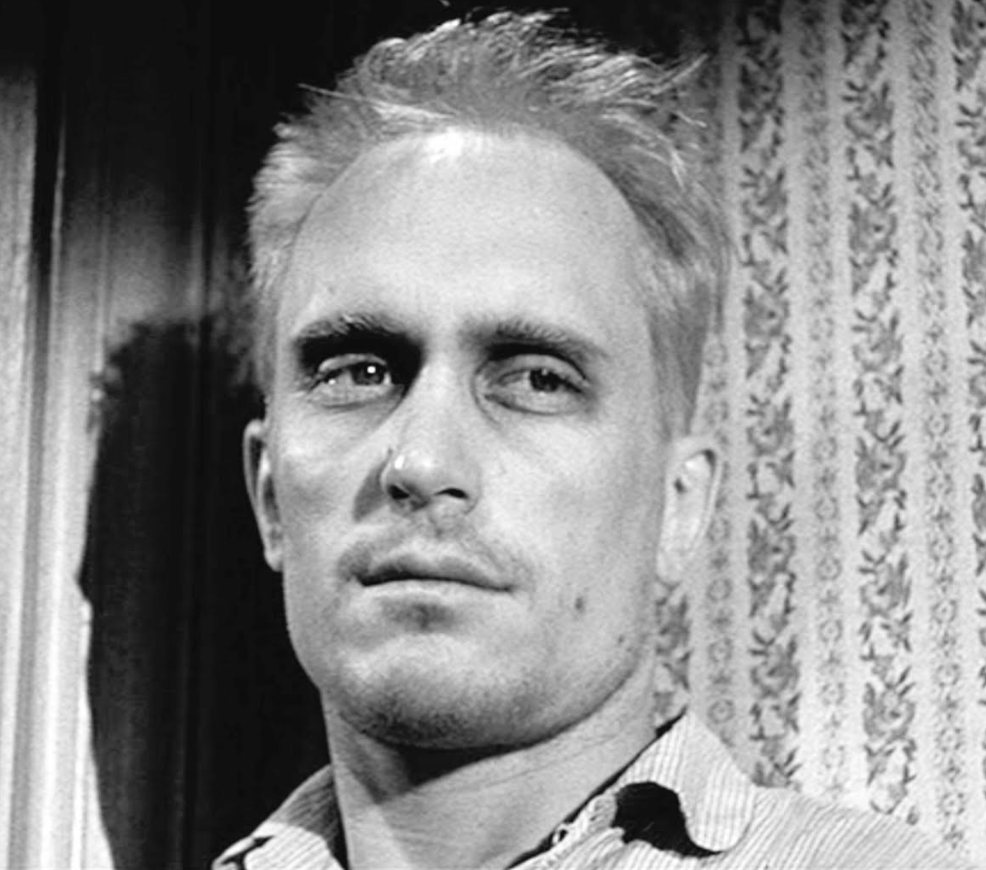

That some were already calling bullshit on the black martyr and white savior stereotypes is heartening.  And, as is so often the case with mid-century Hollywood fare, a queerness disrupts the polarity Sarris describes. Against a backdrop of broken fences, squawking birds, and leafless trees, oddball recluse Boo Radley (Robert Duvall) is lovingly rendered, as is Scout and Dell’s resistance to gender coding. Peters, Badham, Peck, and even Duvall channel unwritten nuances in their performances (in their eyes, especially), and we’re shown the farrago of desperation and ignorance that spawns the alleged rednecks’ prejudice. Thus Lee’s core value of radical empathy is preserved. Yet the film also deserves Sarris’s condemnation, as it doesn’t deliver one fully fleshed-out character of color. It’s an omission that looms, especially since, by 1962, many were fighting passionately for better representation in the very region where this film is set. Intentionally and unintentionally, “To Kill a Mockingbird” reminds us some innocence deserves to be lost.

And, as is so often the case with mid-century Hollywood fare, a queerness disrupts the polarity Sarris describes. Against a backdrop of broken fences, squawking birds, and leafless trees, oddball recluse Boo Radley (Robert Duvall) is lovingly rendered, as is Scout and Dell’s resistance to gender coding. Peters, Badham, Peck, and even Duvall channel unwritten nuances in their performances (in their eyes, especially), and we’re shown the farrago of desperation and ignorance that spawns the alleged rednecks’ prejudice. Thus Lee’s core value of radical empathy is preserved. Yet the film also deserves Sarris’s condemnation, as it doesn’t deliver one fully fleshed-out character of color. It’s an omission that looms, especially since, by 1962, many were fighting passionately for better representation in the very region where this film is set. Intentionally and unintentionally, “To Kill a Mockingbird” reminds us some innocence deserves to be lost.

This originally appeared on Signature.