“Sully” begins with a plane crash – a wobbly, fiery descent right into a Manhattan skyscraper. It’s a nightmare of Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, who in 2009 saved 155 people by landing U.S. Airways Flight 1549 in the Hudson River, and whose subsequent memoir, Highest Duty, provides the backbone of this film. It’s also a traumatic, what-if reference to September 11, 2001, which makes the timing of this release a mite cynical. In fact, undertaking this film at all is a mite cynical, or at least misguided. Because Captain Sullenberger’s heroics took only 208 seconds, fashioning a full-length feature worthy of it would entail another feat of heroism, and director Clint Eastwood isn’t the right knight for the job, not even with a white-haired, white-mustachioed Tom Hanks at the helm as the titular character.

“Sully” begins with a plane crash – a wobbly, fiery descent right into a Manhattan skyscraper. It’s a nightmare of Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, who in 2009 saved 155 people by landing U.S. Airways Flight 1549 in the Hudson River, and whose subsequent memoir, Highest Duty, provides the backbone of this film. It’s also a traumatic, what-if reference to September 11, 2001, which makes the timing of this release a mite cynical. In fact, undertaking this film at all is a mite cynical, or at least misguided. Because Captain Sullenberger’s heroics took only 208 seconds, fashioning a full-length feature worthy of it would entail another feat of heroism, and director Clint Eastwood isn’t the right knight for the job, not even with a white-haired, white-mustachioed Tom Hanks at the helm as the titular character.

Working from Todd Komarnicki’s screenplay, Eastwood attempts to build out dramatic tension, not only with that dramatic CGI opener (an echo of the opening sequence in his tsunami clunker, “Hereafter”) and by slowly meting out details of what really happened in the ill-fated flight. The conceit here is that, once the waves calmed on Sully’s save, National Transportation Safety Board investigators questioned whether the flight captain had unnecessarily endangered his passengers’ lives with his emergency water landing.

According to protocol, Sully should have returned to LaGuardia Airport or tried to land at New Jersey’s Teterboro Airport, and both the airline’s insurance company and Sully wrangle with the consequences of his decision. But while zooming in on the pilot’s growing self-doubt and post-traumatic stress adds a much-needed depth to this tale, demonizing the commission feels like a flimsy effort to make a mountain out of a 208-second-long molehill.

As wise-cracking co-pilot Jeff Skiles, Aaron Eckhart is meant to supply much-needed comic relief, but the actor’s affability reads as glib here, making him seem as if he’s in another movie altogether. The few female characters are hand-on-the-hip nags (an unfortunate Eastwood staple): As Sully’s wife, Laura Linney natters on about bills and feeling overwhelmed while he stares blankly out windows; as an airline investigator intent on tripping up the pilot, Anna Gunn is a Stepford bureaucrat whose smirk is her one note. In general, tone is a huge problem. With drifting flashbacks and flat colorization, it’s un-compellingly dirgelike, especially for an event with a well-known happy ending, and Christian Jacob’s jazz score only adds to the dissonance. Subplots help – a sidebar about a man separated from his son in the aftermath of the crash; the air traffic controller relieved he hasn’t helped kill scores of people after all – but they fall to the wayside as the film circles obsessively back to the crash, filling in salient details each time until the actual hearing is under way.

As wise-cracking co-pilot Jeff Skiles, Aaron Eckhart is meant to supply much-needed comic relief, but the actor’s affability reads as glib here, making him seem as if he’s in another movie altogether. The few female characters are hand-on-the-hip nags (an unfortunate Eastwood staple): As Sully’s wife, Laura Linney natters on about bills and feeling overwhelmed while he stares blankly out windows; as an airline investigator intent on tripping up the pilot, Anna Gunn is a Stepford bureaucrat whose smirk is her one note. In general, tone is a huge problem. With drifting flashbacks and flat colorization, it’s un-compellingly dirgelike, especially for an event with a well-known happy ending, and Christian Jacob’s jazz score only adds to the dissonance. Subplots help – a sidebar about a man separated from his son in the aftermath of the crash; the air traffic controller relieved he hasn’t helped kill scores of people after all – but they fall to the wayside as the film circles obsessively back to the crash, filling in salient details each time until the actual hearing is under way.

To the degree that “Sully” does work, it’s thanks to Hanks (a phrase that sounds like his theme song). Now sixty years old, he’s often described as a modern Jimmy Stewart, but his work radiates more sensitivity and generosity than Stewart’s ever did. What the two actors do share is a dark impatience running beneath all that aw-shucks cheer. It’s a quality that made even “It’s a Wonderful Life” seem like a noir, and one that gives “Sully” a heft it otherwise sorely lacks. But with his characteristically inert filmmaking, Eastwood often cuts away from Hanks’s nuanced expressions, and so the actor reads as more frozen than ever before. The raw vulnerability that distinguished his performance as that other captain who saved his passengers (“Captain Phillips”) is nowhere to be found. Instead, Eastwood has managed to reduce Hanks to his own long-faced laconism. Despite all the shit heaped upon Woody Allen for casting actors as pallid imitations of himself, Eastwood never takes it on the chin for doing the same thing on the rare occasions he doesn’t cast himself as lead.

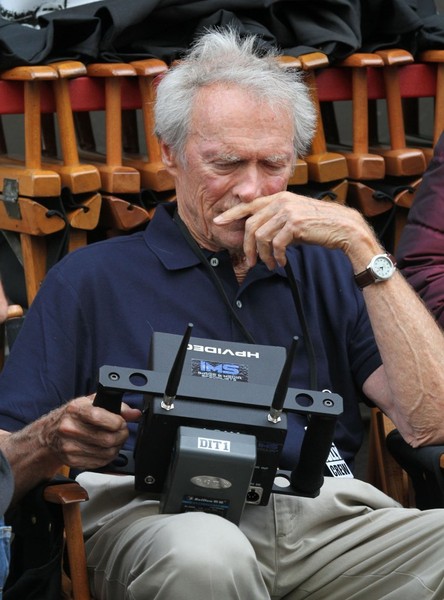

There’s a self-aggrandizing subtext to this entire endeavor, for it’s no mystery why this eighty-six-year-old filmmaker might have been attracted to the story of a seasoned captain who prevails despite his industry’s over-reliance on computer simulation and corporate mumbo-jumbo. Even ignoring his politics, I’ve long felt Eastwood is the emperor with no clothes. The compliments heaped upon his work feel like faint praise – “unpretentious” is code for “dour”; “unfussy” is code for “bland” – and his brand of hyper-masculine grit is actually the worst kind of Hollywood sentimentalism. Though “Sully” is by no means Eastwood’s worst film – that honor is reserved for 2002’s “Blood Work” – it does achieve the impossible. It makes an unlikeable film out of one of the few feel-good stories of the aughts.

There’s a self-aggrandizing subtext to this entire endeavor, for it’s no mystery why this eighty-six-year-old filmmaker might have been attracted to the story of a seasoned captain who prevails despite his industry’s over-reliance on computer simulation and corporate mumbo-jumbo. Even ignoring his politics, I’ve long felt Eastwood is the emperor with no clothes. The compliments heaped upon his work feel like faint praise – “unpretentious” is code for “dour”; “unfussy” is code for “bland” – and his brand of hyper-masculine grit is actually the worst kind of Hollywood sentimentalism. Though “Sully” is by no means Eastwood’s worst film – that honor is reserved for 2002’s “Blood Work” – it does achieve the impossible. It makes an unlikeable film out of one of the few feel-good stories of the aughts.

This originally was published on Signature.