Science fiction has always best served those not served by their current reality. Utopias proscribe alternatives to a reality increasingly hostile to many; dystopias highlight destructive elements while we still can change them; and all speculative tales offer metaphors that double as handy tools in the fight for social change. Alas, not all sci-fi advocates for social justice; some only focuses on wish fulfillment, whether it’s consequence-free sex with mega-hotties or a mastery of the fourth dimension (time). But by marshaling imagination and innovation, the best sci-fi authors grant us a better understanding of ourselves, our world, and all the selves and worlds we can be. Is it any wonder that the genre holds the greatest appeal to those of us who in one way or another are labeled “other” or “in-valid” (with a nod to the 1997 film “Gattaca)? With a bona-fide dystopia now serving as reality, it’s time to explore visions of how else we can live. Here’s a primer of five authors that make a great start.

Science fiction has always best served those not served by their current reality. Utopias proscribe alternatives to a reality increasingly hostile to many; dystopias highlight destructive elements while we still can change them; and all speculative tales offer metaphors that double as handy tools in the fight for social change. Alas, not all sci-fi advocates for social justice; some only focuses on wish fulfillment, whether it’s consequence-free sex with mega-hotties or a mastery of the fourth dimension (time). But by marshaling imagination and innovation, the best sci-fi authors grant us a better understanding of ourselves, our world, and all the selves and worlds we can be. Is it any wonder that the genre holds the greatest appeal to those of us who in one way or another are labeled “other” or “in-valid” (with a nod to the 1997 film “Gattaca)? With a bona-fide dystopia now serving as reality, it’s time to explore visions of how else we can live. Here’s a primer of five authors that make a great start.

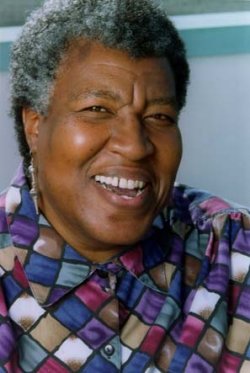

Octavia Butler

Widely considered the gold standard of “afrofuturism,” a term coined in Mark Dery’s essay “Black to the Future” to describe art and literature envisioning new realities for members of the historical African diaspora, the late Octavia Butler created raw yet heartening universes that never denied humanity’s capacity for evil as well as adaptation. All her books blow the mind, but it’s best to start with Lilith’s Brood, a trilogy about an apocalyptic war survivor who is “rescued” by an alien race that wishes to manipulate her genetic material to create offspring. Her dilemma about whether to be “bred” or stay loyal to her species is a powerful analogy for descendants of slaves in the United States.

Samuel R. Delany

A self-described “sex radical,” Samuel R. Delany has made a career of poking at our assumptions about sexuality, race, gender, and storytelling itself. His landmark 1975 novel, Dhalgren, is a great, if demanding, place to start: Set in a fictional Midwestern city cut off from the rest of the world, its confounding narrative follows a Native American journey that rivals Orpheus’s descent. Says the author: “Science fiction isn’t just thinking about the world out there. It’s also thinking about how that world might be – a particularly important exercise for those who are oppressed.”

A self-described “sex radical,” Samuel R. Delany has made a career of poking at our assumptions about sexuality, race, gender, and storytelling itself. His landmark 1975 novel, Dhalgren, is a great, if demanding, place to start: Set in a fictional Midwestern city cut off from the rest of the world, its confounding narrative follows a Native American journey that rivals Orpheus’s descent. Says the author: “Science fiction isn’t just thinking about the world out there. It’s also thinking about how that world might be – a particularly important exercise for those who are oppressed.”

Richard Matheson

Recently deceased Richard Matheson wrote in nearly all genres of speculative fiction (including some key “Twilight Zone” episodes) but his science fiction offers the most useful glimpses into how our species will run amok if we stay our current course. His best entry in this category is also his most influential: 1954’s I Am Legend, which has been adapted to film four times and focuses on the battle of a pandemic’s sole survivor against the undead. As a fable about the detritus of war, dehumanized humans, and the ethics of science and technology, it remains unparalleled.

Ursula K. Le Guin

Like the works of Octavia Butler, Le Guin’s books rarely coddle readers. Rather, these accounts of alternative dimensions – ones with entirely different modes of reproduction, copulation, cohabitation, and sexualization – hold us accountable with a breadth and boldness that inspires rather than alienates us. Her novels The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness may have scored Hugo and Nebula Awards, but I recommend starting with The Lathe of Heaven (1971). Set in a future that is now our past (2002), its narrative about a person who alters the past through their dreams offers frighteningly prescient observations about environmental destruction and racial identification.

but I recommend starting with The Lathe of Heaven (1971). Set in a future that is now our past (2002), its narrative about a person who alters the past through their dreams offers frighteningly prescient observations about environmental destruction and racial identification.

Nnedi Okorafor

Like Matheson, Nnedi Okarafor writes in all genres of speculative fiction, including Young Adult. Raised in Ohio by Nigerian-born parents, she improvises upon American pop culture as well as West African traditions and imagery to build her own creative vocabulary. I recommend starting with 2011’s Who Fears Death. Set in a war-torn region of post-apocalyptic Africa, it focuses on a child of rape whose unique powers make her a target for those guarding what remains of the status quo. Extrapolate away.

This originally appeared in Signature.