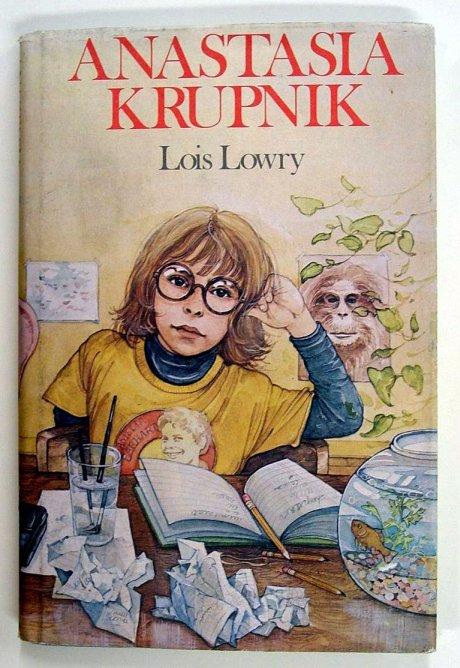

I recently reread a Young Adult series I loved when growing up. A more lighthearted offering from The Giver author Lois Lowry, these books focus on Anastasia Krupnik, a 1980s Newton, Massachusetts, tween whose mother is a painter, father is a poetry professor, and toddler brother already reads and speaks in carefully parsed sentences. Anastasia is kind, idiosyncratic, and funny, and she wrangles with moral dilemmas and the indignities of adolescence with a nerdy charisma that, at the ripe old age of (number redacted), I still find irresistible. Anastasia is also white.

I recently reread a Young Adult series I loved when growing up. A more lighthearted offering from The Giver author Lois Lowry, these books focus on Anastasia Krupnik, a 1980s Newton, Massachusetts, tween whose mother is a painter, father is a poetry professor, and toddler brother already reads and speaks in carefully parsed sentences. Anastasia is kind, idiosyncratic, and funny, and she wrangles with moral dilemmas and the indignities of adolescence with a nerdy charisma that, at the ripe old age of (number redacted), I still find irresistible. Anastasia is also white.

I mention this fact because the only time race is mentioned in this book series is when someone is not white. The example that most stands out is the character of Henry in Anastasia’s Chosen Career, the seventh book in this series. Henry is a tall female student in the modeling course Anastasia takes while casting about for a career (age thirteen being high time to figure out what you’re doing with the rest of your life, apparently). A live-wire from the Boston neighborhood of Dorchester, Henry often says what Anastasia only thinks. She is also black. We know this because it’s specifically stated in her first appearance in the book, though she does not often speak in what could be coded as a black vernacular. Because Anastasia may not have many friends of color, Henry’s race may indeed be noteworthy to her although the two girls find everything about each other’s lives fascinating and foreign. But the minute that Henry is labeled black while other, presumably nonblack characters are not assigned a race, we suddenly realize Anastasia’s world is, by default, white. In that one swoop, the book’s Eden is destroyed, and readers are denied a freedom of imagination as well as a freedom of identification.

I don’t mean to single out Lowry, whose books offer progressive examinations of oppressive hierarchies. She likely harbored no ill intent and in fact may have been looking to create more “diverse” representation. But when characters’ race are only mentioned when they’re nonwhite, the implication is that what’s neutral is what’s white. Readers are suddenly robbed of the ability to imagine the characters as whatever race (or religion or eye color) they like. And kids reading the books who are nonwhite are suddenly rendered “others” – what Audre Lorde once famously dubbed “sister outsiders.” No doubt such labeling subtly impacted my and other young readers’ comprehension of race.

You could argue, what’s the alternative? The book is grounded in a specific geographic location and to pretend otherwise is silly. Anastasia is a denizen of Newton, a Greater Boston suburb that Lowry must have assumed was mostly white. You also can argue that Anastasia simply  doesn’t know many people of color so to ignore Henry’s race is misguided as the story takes Anastasia’s perspective. But here’s the thing: I actually grew up in this town in the 1980s. (My father also is a professor and my mother is an artist; if the technology had been in place, I would have sworn Lowry spied on us with a webcam.) At the time of the Anastasia series, Newton’s public school population was very racially mixed because of the Boston desegregation busing program, and because there was a prominent black neighborhood in the western section of the town. I mention this not to nitpick but because the old saw is true: To assume is to make an ass out of you and me. This is especially true when the assumption in question concerns our country’s most divisive, explosive issue since slaves were brought to its shores.

doesn’t know many people of color so to ignore Henry’s race is misguided as the story takes Anastasia’s perspective. But here’s the thing: I actually grew up in this town in the 1980s. (My father also is a professor and my mother is an artist; if the technology had been in place, I would have sworn Lowry spied on us with a webcam.) At the time of the Anastasia series, Newton’s public school population was very racially mixed because of the Boston desegregation busing program, and because there was a prominent black neighborhood in the western section of the town. I mention this not to nitpick but because the old saw is true: To assume is to make an ass out of you and me. This is especially true when the assumption in question concerns our country’s most divisive, explosive issue since slaves were brought to its shores.

Lowry’s Henry – whom Anastasia adores and who is a lovingly cantankerous, fully fleshed-out character who has her own sympathetic arc and set of revelations – is no mere “noble negro,” the term used for characters of color who exist only to aid white people’s personal growth. But identifying her race is nonetheless a complex choice. Why not use class or neighborhood to emphasize her uniqueness to Anastasia instead?

I often think about the issue of racial identification while rereading favorite books. Many, many white authors I love – from Sue Miller to Edmund White to Marge Piercy to J.M. Coetzee – tend to identify race more frequently when someone is nonwhite. Of course, the truth is that many writers of color identify the race of their white characters more frequently, but to act like this is the same thing is like substituting “all lives matters” for “black lives matter,” thereby denying the reality that people of color are more endangered in this country than white people. Does singling out the race of nonwhite characters make white authors racist? Not necessarily, but the act rightfully can be perceived as a micro-aggression – the perpetuation of the assumption that “white is right,” or at least “normal.” What’s the solution? I’m not sure, but I do know that when white authors single out the race of nonwhite characters, they can perpetuate unconscious biases. Perhaps we need a sort of Bechdel Test for racial identification in literature.

Some questions worthy of consideration:

1. Does identifying the race of a character represent the perspective of the narrator (or other speaker within the book) or the bias of the author?

2. Is identifying the race of a character necessary to further the plot or a theme?

3. Would you feel comfortable identifying a character’s race in this context and in this manner in front of a person of this given race?

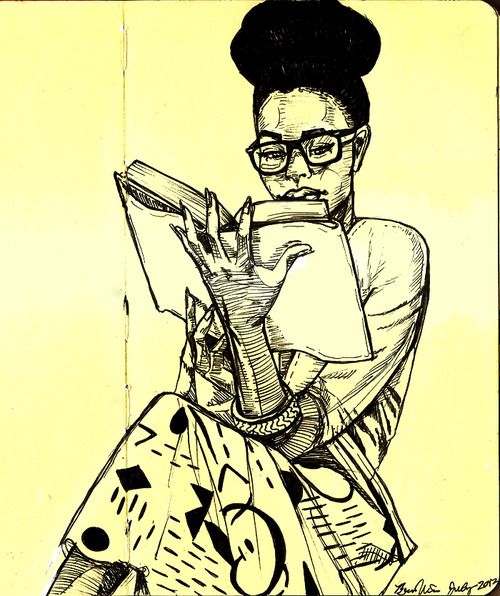

I am sure there are many more questions to contemplate, and that I have perpetuated some micro-aggressions even as I have attempted to address this issue. I’m open to corrections. In fact, what is most important when it comes to these profoundly charged topics is to remain open and conscious. (That, and not putting the onus on those coded as “other” to correct and educate others.) For while it is true that race identification can enable us to empathize with a greater range of people, it so often also perpetuates our biases. The specific joy – the specific liberty – that books offer us is a wonderland that we co-create when we read them. The details an author omits are as important as the ones she includes, for we get to fill those gaps with our own imaginations. Above all, it is vital that the mysterious, magical world of literature remain open to everyone, for reading remains our best way to consider and correct the human condition.

I am sure there are many more questions to contemplate, and that I have perpetuated some micro-aggressions even as I have attempted to address this issue. I’m open to corrections. In fact, what is most important when it comes to these profoundly charged topics is to remain open and conscious. (That, and not putting the onus on those coded as “other” to correct and educate others.) For while it is true that race identification can enable us to empathize with a greater range of people, it so often also perpetuates our biases. The specific joy – the specific liberty – that books offer us is a wonderland that we co-create when we read them. The details an author omits are as important as the ones she includes, for we get to fill those gaps with our own imaginations. Above all, it is vital that the mysterious, magical world of literature remain open to everyone, for reading remains our best way to consider and correct the human condition.

This was originally published at Signature.