Anyone who really loves show business eventually has a “come to Fosse” moment. You know you’ve become a true convert to the choreographer and director when you come around on “All That Jazz,” his bombastic meta-movie biography-musical. And you know you’ve gone ahead and joined his cult when you come around on his last film, “Star 80,” about slain porn star Dorothy Stratten. (I’ve yet to unlock that level.) But even if you don’t dig Fosse – even if you don’t consciously know Fosse – chances are good you’ve fallen under his influence. Born in 1927, his signature style didn’t just indelibly stamp the world of dance. It redefined the packaging of sexuality and entertainment, blurring worlds that post-World War II parochialism had strenuously separated.

Anyone who really loves show business eventually has a “come to Fosse” moment. You know you’ve become a true convert to the choreographer and director when you come around on “All That Jazz,” his bombastic meta-movie biography-musical. And you know you’ve gone ahead and joined his cult when you come around on his last film, “Star 80,” about slain porn star Dorothy Stratten. (I’ve yet to unlock that level.) But even if you don’t dig Fosse – even if you don’t consciously know Fosse – chances are good you’ve fallen under his influence. Born in 1927, his signature style didn’t just indelibly stamp the world of dance. It redefined the packaging of sexuality and entertainment, blurring worlds that post-World War II parochialism had strenuously separated.

I first saw “All That Jazz,” Bob Fosse’s signature directorial effort – though not the one that nabbed him a best-directing Oscar – in its initial 1979 run, and was singularly unimpressed. Of course, I was age eight, and more impressed by “The Muppet Movie.” Years later, I saw what I had missed. Buried in the film’s dance sequences, its half-assembled spangled costumes and bare-bones Broadway backstages and editing rooms, was a winking homage to narcissism and its opposite, true communion. It was, and is, an amazing cacophony. But it is also bloated by his death wish – a courtship with his own demise that he materialized by casting Jessica Lange, one of his many girlfriends, in the role of Angelica, a literal angel of death.

The issue of women was central for Fosse, as it is for everyone born, really. But Fosse was legendarily conflicted, and in dance he explored this conflict so charismatically – charisma being his central legacy – that his expression of these conflicts became a style unto its own. He got his start as a teenaged dancer in Chicago strip joints, where he earned money to shore his financially struggling family. Though the flair of those environs forever seared him, their sexual dysfunction did as well; in his fantastic biography Fosse, author Sam Wesson confirms that the autobiographic nature of the “All That Jazz” scene in which a young Joe Gideon (Fosse’s stand-in) ejaculates in his pants right before going on stage at a titty club.

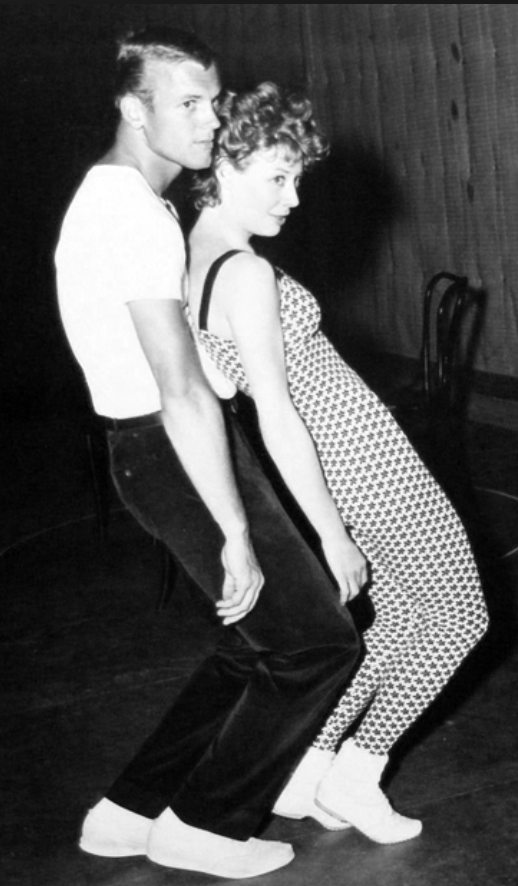

Performing for the USO during World War II and then in Hollywood, Fosse marshalled his bright blue eyes and rangy limbs to ascend in his career. Throughout his life, he romantically partnered with exceptional dancers, often ones more established than him, and dilly-dallied on the side with any pretty lady who struck his fancy.  But while womanizing is hardly a new story for mega-accomplished men, what is noteworthy is Fosse remained close with nearly all his ex-lovers, many of whom also became friends and colleagues with each other. His last wife, the powerhouse Gwen Verdon, often worked with Ann Reinking, arguably Fosse’s greatest disciple and definitely his girlfriend. It’s as if Fosse wasn’t just creating a harem but the ultimate dance company, one vibrating with lust and love at all times.

But while womanizing is hardly a new story for mega-accomplished men, what is noteworthy is Fosse remained close with nearly all his ex-lovers, many of whom also became friends and colleagues with each other. His last wife, the powerhouse Gwen Verdon, often worked with Ann Reinking, arguably Fosse’s greatest disciple and definitely his girlfriend. It’s as if Fosse wasn’t just creating a harem but the ultimate dance company, one vibrating with lust and love at all times.

I mention all this not out of prurience (nor prudishness), but because this sensuality – at once crisp and liquid, silly and serious – forms the backbone of the Fosse brand. Once he accepted his limitations as a dancer, he turned his eye to directing and choreographing on stage and film, apprenticing with Jerome Robbins in the making of “The Pajama Game” before going out on his own. From the very first of Fosse’s productions, you can see how he constructed the dance equivalent of abstract expressionism: tipped bowler hats, pelvic thrusts, hunched shoulders, turned-in feet, and a hyper-articulation of the hands emphasized by Charlie Chaplin-style white gloves. It was sex with a quotation mark and exclamation point all at once – punctuation as percussion.

In Fosse’s work flowed the brass tacks of vaudeville (pratfalls, double takes, sleights of hands) and the flourishes of mid-century Tinseltown (gracefully extended limbs, overarched spines), particularly those of Fred Astaire and Busby Berkeley. Married with his trademark erosion of the fourth wall, Fosse’s from-the-hip, hat-over-the-eye economy normalized all sorts of transgressions and paved the way for the twenty-first century’s “irony-is-the-new-black” ethos and aesthetic. This, despite the fact that he died in 1987–and pretty much exactly the manner “All That Jazz” foreshadows. (He keeled over from a heart attack near a Washington, D.C., theater while accompanied by Verdon.)

Every major icon of the last forty years owes Bobby – from Michael Jackson to Liza Minnelli to Madonna to Britney Spears to Lady Gaga and even Beyoncé. Fashion would not be fashion without his exposed garter belts and fishnet stockings – more of his backstage-as-front-stage ethos – and it took the world decades to catch up with his matter-of-fact mingling of races and sexualities. His integrations didn’t seem intellectually derived so much as a no-muss, no-fuss privileging of talent and originality wherever it could be found.

And as a film director, Fosse may be underrated to this day. Though “Cabaret,” his first Hollywood feature, was widely adored, other films – especially “All That Jazz” and “Sweet Charity” – haven’t always received their due. In the case of “Star 80” and “Lenny,” his oddly unfunny film about comedian Lenny Bruce, this may be fair, though both tear into American hypocrisies with an admirable zeal. But “Charity” and “Jazz” take their cues from Fosse’s choreography with an acumen that is widely imitated. In “Requiem for a Dream,” director Darren Aronofsky ripped off the repetition of “Jazz”‘s sad-clown morning ritual, and director Michael Bennett won all kinds of awards for “A Chorus Line,” his musical about a Broadway tryout, though the first ten minutes of “Jazz” covers the same ground with infinitely more panache.

And as a film director, Fosse may be underrated to this day. Though “Cabaret,” his first Hollywood feature, was widely adored, other films – especially “All That Jazz” and “Sweet Charity” – haven’t always received their due. In the case of “Star 80” and “Lenny,” his oddly unfunny film about comedian Lenny Bruce, this may be fair, though both tear into American hypocrisies with an admirable zeal. But “Charity” and “Jazz” take their cues from Fosse’s choreography with an acumen that is widely imitated. In “Requiem for a Dream,” director Darren Aronofsky ripped off the repetition of “Jazz”‘s sad-clown morning ritual, and director Michael Bennett won all kinds of awards for “A Chorus Line,” his musical about a Broadway tryout, though the first ten minutes of “Jazz” covers the same ground with infinitely more panache.

Fosse’s secret, or one of them, anyway, was a syncopation that defined his cinematography as well as his editing. With jump cuts, subliminal blips, and unique perspective shots, he really did direct like a dancer. (It’s no coincidence that Gene Kelly co-directed “Singin’ in the Rain,” the only dance movie better than his own.) The rhythms were so tight that they allowed Bobby an indulgence that, admittedly, wasn’t for everyone. Nearly all his film and stage productions are marked by extended dance sequences and montages – those homages to 1960s “be-in” scenes in “Charity,” pretty much every scene in “Pippin,” and that seemingly endless death that comprises the last thirty minutes of “Jazz.” A grownup behind me muttered “Die, already” when I saw the latter in a Boston moviehouse.

Accepting that scene earmarks you as a true Fosse head, I think, and now I watch it all the time. It’s the ultimate dance on one’s grave, and I like it best with the sound off so I can ogle the feathers and skin-tight sequins, the rolled eyes and hips, with zero distractions.  Its brilliance lies in its length, ironically, for the deliberate layering of all the master’s tropes results in a delicious wedding cake of his anxieties that encourages you to digest your own.

Its brilliance lies in its length, ironically, for the deliberate layering of all the master’s tropes results in a delicious wedding cake of his anxieties that encourages you to digest your own.

With his various addictions and pathologies – his bottomless, wildly documented despair – Fosse for sure made everything all about him. But his core generosity and genius was that he saw himself as part of everything and everybody. It’s why he transcended the bleak narcissism that was his eternal starting point, why his humor always bested his bathos, and why real life always triumphs over razzle-dazzle in his work. More than anyone else in show-business before or since, Fosse knew how to make lemonade. Better yet, he knew how to sell it.

This was originally published on Signature.