I grew up outside of Boston, a stone’s throw from Walden Pond. Every summer I prowled through its woods and floated in its shadowy waters; I dated one of its rangers. Because of this, I considered Henry David Thoreau to be a neighbor and a mentor, and his Walden to be a sort of local pamphlet, not unlike a collection of blueberry recipes you might find in a Maine library. It wasn’t until I left home that I grasped the full impact of his screed. Thoreau didn’t just immortalize my neighborhood; he offered an anti-establishment, back-to-nature alternative to the Manifest Destiny mishegos that has run rampant in this country since its inception.

I grew up outside of Boston, a stone’s throw from Walden Pond. Every summer I prowled through its woods and floated in its shadowy waters; I dated one of its rangers. Because of this, I considered Henry David Thoreau to be a neighbor and a mentor, and his Walden to be a sort of local pamphlet, not unlike a collection of blueberry recipes you might find in a Maine library. It wasn’t until I left home that I grasped the full impact of his screed. Thoreau didn’t just immortalize my neighborhood; he offered an anti-establishment, back-to-nature alternative to the Manifest Destiny mishegos that has run rampant in this country since its inception.

Of course, my younger perception of Thoreau was also accurate. Though he abandoned a career in pedagogy soon after leaving Harvard, Walden can be read not only as a meditation but as the sort of educational pamphlet that used to fuel social movements; it goes so far as to dictate how many chairs we should own and what beverages we should consume. (Answer: Nothing but water, son.) Dying in his hometown of Concord, Massachusetts, at age forty-four – he would have celebrated his two-hundredth birthday this month – he remained a local boy for most of his life. Certainly his “hermit saint” persona – an “ignore thy neighbor” isolationism coupled with a passion for social justice (he was a fierce abolitionist and tax resister) – was completely and totally New England.

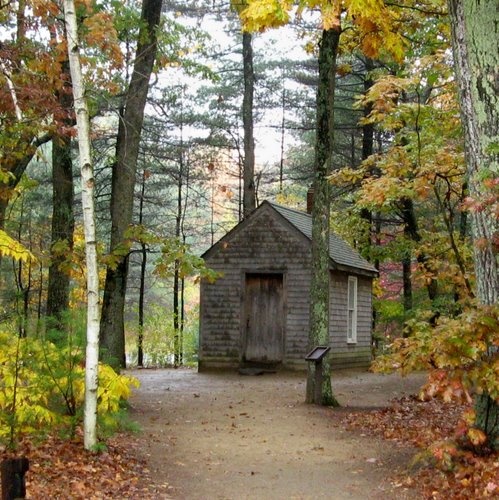

Of course, the “hermit-saint” persona is impractical for any swath of time when not absolutely necessary, and the writer-philosopher was actually within a stone’s throw of family and supposedly snuck over to his aunt’s house for cookies every week during his infamous tenure in the solo, “remote” shelter that actually was located on buddy Ralph Waldo Emerson’s land. (This is even funnier given the restrictive, no-sugar diet he prescribed.) Over the last two centuries, some have taken umbrage with Walden – with its misanthropic asceticism; with its libertarianism and factual liberties regarding the “working man,” especially. Even E. B. White, who loved the philosopher’s work so much that he emulated his retreat from society by abandoning New York City for rural Maine, acknowledged that Walden is “full of contradictions and cryptic utterances.” But he also wrote: “Many of Thoreau’s sentences cover whole areas of modern life and the modern dilemma. The way to read him is to enjoy his enthusiasms, his acute perception.” As he so often did, the New Yorker essayist and children’s book author hit the nail on the head.

Perhaps the best way to remember Thoreau – if not to outright revere him – is as a utopian. Indeed, the self-proclaimed alienist belonged to an entire community of utopians: the Transcendentalists, including Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, and Amos Bronson Alcott, father of Little Women author Louisa. Although this crew lived in the same region of Massachusetts, it would be a stretch to call them a collective. Instead, they comprised a school (in Alcott’s case, literally) – one that espoused a faith in hard work and in nature, especially in the sense that God manifested as everything and everyone. Transcendentalism departed from Calvinism in that it emphasized joy; it departed from paganism in that it emphasized purity.

But what Thoreau uniquely offered us was a utopia of one. If Hawthorne and Alcott were forever trying out such social experiment communities as Fruitlands and Brook Farms, Thoreau – who in Walden declared “To be in company, even with the best, is soon wearisome and dissipating …. I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude” – made a religion out of self-reliance. He may have declared it “wholesome to be alone the greater part of the time,” but he also enjoyed being alone. He read, he wrote, and he communed – not only with his own higher self but with nature. Nothing is more rapturous than the passages in which he simply observes his environs. Some are pure poetry.

To live alone, he suggested, was not just acceptable but ideal. Utopian, in fact. And a utopia by definition is a perfect place and no place – a place to strive for rather than inhabit; a place that does not and cannot exist. In this sense, his sometimes-ungrounded idealism was, in fact, ideal. It introduced templates – environmental philosophy and preservationism; a peaceful, anti-business brand of civil disobedience; an embrace of solitude and silence – that are even more precious today.

Here in his future, Thoreau’s “less is more” rhapsody remains utopian.

This originally was published at Signature.