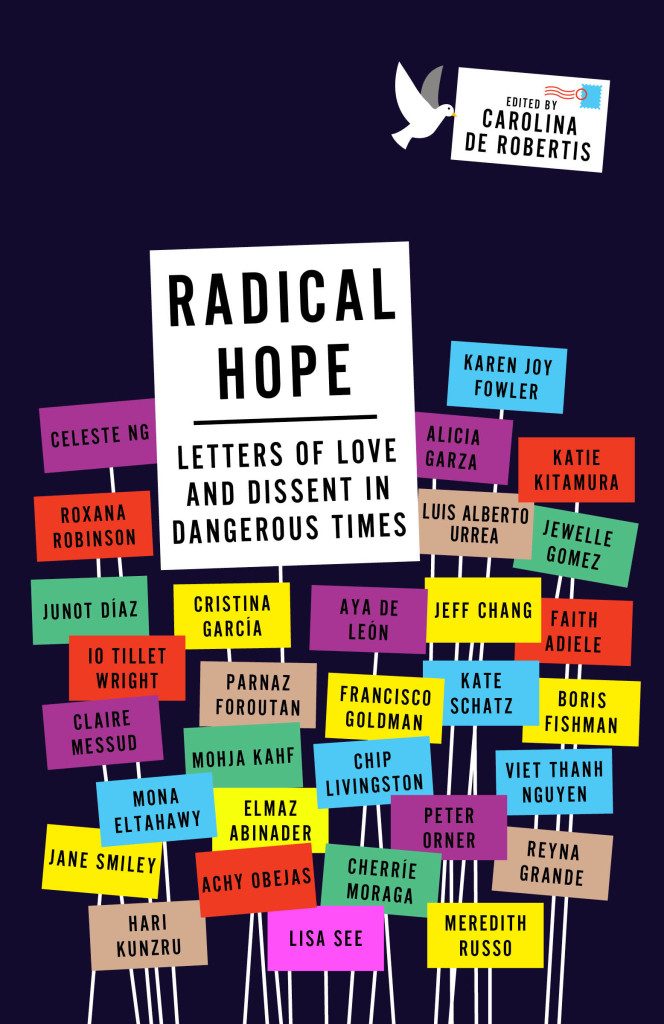

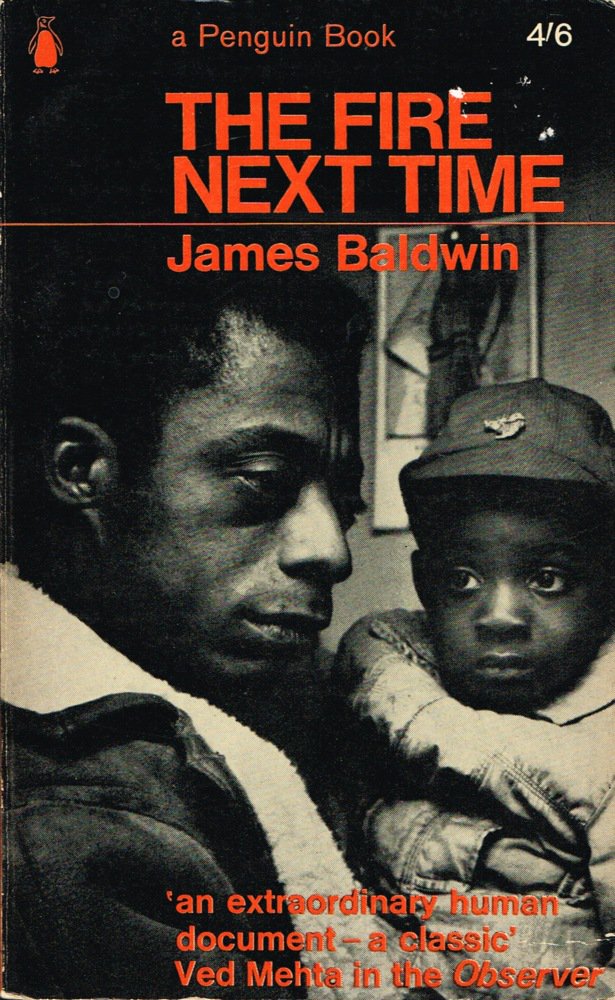

An award-winning novelist and literary translator, Carolina de Robertis has donned a new hat for her latest literary effort, that of anthology editor. In the wake of the November 2016 U.S. presidential election, she put out a call for politically inflected love letters in the tradition of James Baldwin’s 1963 The Fire Next Time essay, “My Dungeon Shook: A Letter to My Nephew.” The result is Radical Hope, a series of epistolary essays that are bound to shore progressives in the months and years to come. We discussed this remarkable collection with de Robertis, who lives in San Francisco with her wife and children.

An award-winning novelist and literary translator, Carolina de Robertis has donned a new hat for her latest literary effort, that of anthology editor. In the wake of the November 2016 U.S. presidential election, she put out a call for politically inflected love letters in the tradition of James Baldwin’s 1963 The Fire Next Time essay, “My Dungeon Shook: A Letter to My Nephew.” The result is Radical Hope, a series of epistolary essays that are bound to shore progressives in the months and years to come. We discussed this remarkable collection with de Robertis, who lives in San Francisco with her wife and children.

LISA ROSMAN: Let’s start with nuts and bolts. Is this book merely a response to the election of Donald Trump?

CAROLINA DE ROBERTIS: It’s not just about the election of Trump because I think it’s important to extend our gaze to something larger and deeper in our country, though he as an individual is certainly his own kettle of dangerous fish.

The idea came to me three days after the election. I was sitting at my writing desk unable to work on my own novel, and I was thinking about how writers might be able to respond and contribute to the dissent and resistance that was going to be necessary in the coming social and political climate. I have a big photograph of Baldwin hanging over my writing desk and I couldn’t stop thinking about that essay in which he addresses his nephew. It seemed to me that his form of letter-essay was particularly helpful for blending personal reflections with sweeping political analysis, a blend we very much need in these times.

LR: Do you view this collection of letters as an antidote to the way social media has proven divisive and reductive around many political issues?

CDR: Social media is a profoundly useful tool that has allowed many people at the social margins to have more of an impact on mainstream culture. Look at the impact of #oscarsowhite or the effect on the Twitter protesting of the Kendall Jenner Pepsi commercial. A lot of racism was just an accepted part of the culture until people had these tools for expressing their dissent.

But social media also moves blindingly fast and can have the tendency to reduce complex human realities to tiny sound bites. So I do believe we still need books to be part of our cultural conversation so we can go a little deeper and have more of a human conversation with ideas and deeper selves.

LR: In your introduction, you say dissent is “not unrelated to love.”

CDR: The tide of backlash that has been rising has been lacking in love and it is not who we are as a nation. I deeply believe that the majority of our country is fundamentally progressive and cares about the well-being of our fellow humans. For myself as a gay married woman, as an immigrant, as a Latina, I have watched extraordinary waves of compassion and connectedness be part of this culture in increasing ways. So when those in institutional power deny the humanity of many members of society, love – and speaking that love – is an act of dissent. Just affirming the humanity of Mexican and Central American immigrants is an act of dissent and an act of love, for example. Many of us are so depleted by the level of vitriol in our current conversation that we need both so we can connect back to human dignity.

LR: Was timeliness a concern of this anthology given how rapidly our political climate is shifting?

CDR: These essays were turned around really quickly between the November 2016 election and the January 2017 inauguration. I’m incredibly grateful to my publisher and the writers who were willing to take this train ride with me. There was a feeling that we had other media sources to address specific events, and that we wanted this book to instead sink a little deeper into the cultural effects that rise in threat and repression and instability. Some of the pieces in this book now read as preternaturally prophetic because they are looking at the dangers of having an unstable, corrupt president that we are already experiencing.

LR: Is the hope that these essays will provide solidarity or a blueprint for people as they resist the current administration?

CDR: Absolutely. My hope is that they will provide readers with whatever they need to keep going through what are difficult and challenging times for anyone who holds and cherishes progressive values. I thought a lot in the conception of this book about my grandmother who died under Uruguay dictatorship. She was a social justice activist who never saw that dictatorship lift. She told me about how she managed to keep working when things seemed hopeless, and how she was able to trust that better times were coming and that she was part of feeding that, because we all can be. My hope is that this book is a form of sustenance for anyone who wants to stay sane and awake and engaged in these times, because we have a lot of work to do to preserve the values we hold dear and we have a lot of agency to do so as I think recent current events, like protests of the Muslim Ban, have shown.

LR: How did you select the voices in this collection?

CDR: One of the things that happened with this election is that Trump and his campaign used racism and transphobia and homophobia and Muslimphobia to gain votes. It is important that we remember that he was voted in by only a quarter of the population – not the true majority of our nation. That is to say, this is not who we really are! And so in response I wanted to present a broad range of voices.

We needed to hear from people like Meredith Russo, who in the essay “The Most Important Act of Resistance” tells us what it is like to be a transgender mother in Tennessee today. We needed to hear from people like Mohja Kahf, who wears a headscarf in Arkansas and is Syrian-American, and writes with incredible humor and insight and wisdom.

I think if she’s going to keep on living her truth, then who am I not to? So I curated a list of thinkers and writers in my network and reached out to them. I was floored by the level of response from really luminary and busy writers, like Pulitzer Prize winners Junot Diaz and Jane Smiley, Booker Prize finalist Karen Joy Fowler, and Cherrie Moraga, who co-edited the anthology This Bridge Called My Back. This is the time when we need to hear from brilliant women of color like her, and Native American poets who happen to be gay, like Chip Livingston who channels the voice of his deceased grandfather. We need Jewelle Gomez, whose story of the ancestor who raised her brings nuanced ideas to light about how our survival through these hard times can be rooted by people who survived other hard times in the history of the United States.

LR: Do you view this last election as a backlash against progress that had been made?

LR: Do you view this last election as a backlash against progress that had been made?

CDR: Yes. And that backlash can be incredibly painful and can affect real people’s lives in ways that are extremely harmful, but is also a sign that we have made strides. Luis Alberto Urrea writes so beautifully about this here in “Grace and Karma Under Orange Caesar” as does Boris Fishman, who in “Dear Mr Roell” writes to one Trump supporter he read about it in the newspaper. All this is to say that we have more than anger to fuel our vision. I don’t mean to discredit the anger, but we also have love and a celebration of the strides that we have made and a recognition that the quest to create a society that is just and safe for everyone is extremely long. This book is a kaleidoscope of voices who are contributing to this resistance, and an invitation to those who want to sing along as well.

This was originally published on Signature.