Much has been made of Henri Matisse’s use of color, and much should be. Arguably the most adventurous colorist in the history of art, the artist’s palettes improved upon peak foliage, peak blooms, and the many feathers in a peacock’s plume. The painterly equivalent of a pregnant lady’s incongruous cravings, his hues forever altered Western civilization’s understanding of how color could explode upon a canvas. Along with the introduction of LSD, he and other Fauvists may have been centrally responsible for the rainbow splendor of the 1960s.

Much has been made of Henri Matisse’s use of color, and much should be. Arguably the most adventurous colorist in the history of art, the artist’s palettes improved upon peak foliage, peak blooms, and the many feathers in a peacock’s plume. The painterly equivalent of a pregnant lady’s incongruous cravings, his hues forever altered Western civilization’s understanding of how color could explode upon a canvas. Along with the introduction of LSD, he and other Fauvists may have been centrally responsible for the rainbow splendor of the 1960s.

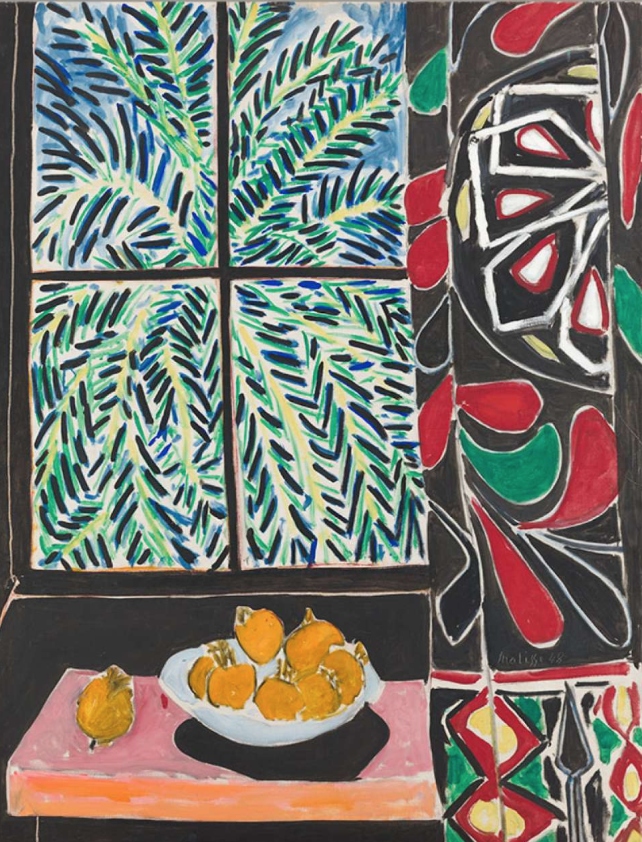

But in “Matisse in the Studio” at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (it’s since moved on to London’s Royal Academy of Arts), the artist’s patterns are as important as his palettes. Spanning fifty years, the show is organized into five sections – “The Object Is an Actor,” “The Nude,” “The Face,” “Studio as Theatre,” and “Essential Forms” – and features his paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, and cutouts as well as key possessions that inspired him. Not all of these objects of affection are high-falutin’; among them are a chocolate pot, a green glass vase, a short chair, a pewter jug, haitis (embroidered hanging cloths) from North Africa, and masks and figurines from sub-Saharan Africa. But he appreciated each enough to use in his work again and again. “He acquired things not because of their material worth, but because of how they spoke to him,” MFA co-curator Helen Burnham has said.

In his paintings, aglow with ochres and mauves and tomato reds, female subjects do not dominate so much as contribute shapes and shades to whole series of shapes and shades. In what has been called a “quantity-quality equation,” areas of color, each marked by a different pattern, are arranged across his canvases so that they are all accorded their own value. In Matisse the Master, Hilary Spurling quotes him as saying: “Peace and harmony is always my aim.” With everything as foreground and therefore background too, this aim is abundantly evident. Each of his canvases constitutes a flourishing democracy, if ever there’s been one. (America should take note.)

Some have taken issue with Matisse’s odalisques – with how his women figures, usually quite abstracted, are equated with objets d’art and even wallpaper. In 1928’s “Odalisque with a Turkish Chair,” the female model’s breasts, hips, and thighs blend with the lines of textiles and wall hangings surrounding her in an effect similar to how a central vase interacts with its environment in 1940’s “Interior with an Etruscan Vase.” Others have accused the painter of culturally appropriating African and Asian art and objectifying non-Western subjects in such works as 1921’s “The Moorish Screen.”

of textiles and wall hangings surrounding her in an effect similar to how a central vase interacts with its environment in 1940’s “Interior with an Etruscan Vase.” Others have accused the painter of culturally appropriating African and Asian art and objectifying non-Western subjects in such works as 1921’s “The Moorish Screen.”

In an interview with the Boston Globe, MFA co-curator Ellen McBreen says, “Matisse clearly shows us that twentieth-century abstraction arguably wouldn’t have happened without a relationship [to non-Western art]…. What do we do with the fact that much of European art was based on an interrogation of objects whose makers were invisible?” These are all valid objections that should continue to be interrogated, though he approached each of his subjects formally enough to encourage others to do so as well.

He may have admired the simplicity of these often-humble objects but the voltage of their utility, the laser purity of their forms is what stands out most in his work. Matisse’s brand of populism stemmed from his embrace of all well-rendered forms, organic and inorganic. In The Unknown Matisse, Hilary Spurling quotes him as saying: “I work without a theory.” You can practically hear him add to himself: Because I worship beauty wherever I see it. Certainly, he was not one to prioritize visual information so much as to bombard us with all the pleasure possible in any tableau.

Working from the 1890s into the 1950s, he counted Picasso among his peers and Cezanne as his favorite Impressionist. (He owned the latter man’s signature “Three Bathers” painting for a time, and admired him for “breaking down forms,” author Sue Roe reports in In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and Modernism in Paris, 1900-1910.) But while anarchists may have surrounded Matisse, he saw art as having a social purpose – namely, integration. Roe writes, “[Matisse believed that] if painting could come closer to a form of decoration, it could surely be introduced into the lives and homes of ordinary working people.” You get the sense, especially in “Matisse in the Studio,” that he wished to make fine arts “artisanal” in the best sense of that word – as useful decoration brightening ordinary life like the objects he most adored. His paintings remind us that color is light – a gift to guide us through the darkness of our days with grace, not just duty. And the elated, montonical simplicity of his latter work – the cutouts made after he was disabled by abdominal surgery – remind us that form-as-function channels pleasure as a distinctly higher power.

Given his twin values of sensuality and contentment, you could call him a bourgeois pagan. Maybe even an enlightened materialist. But you could never call him a hedonist. Unlike Picasso, Henri did not hail from such an upper-class family that he took his hard-won luxuries for granted. Rather, color was his divine guide and that seemingly unruly patterning was a nod to sacred geometry. “Fit your parts onto one another and build them up … like a cathedral,” Roe says he told a favorite pupil. In Matisse’s work, the whole was always greater than the sum of its parts, and joy – the greatest gift of all – transcended any sort of hierarchy.

This was originally published on Signature.