Los Angeles is having quite a moment. Even people with zero interest in the film business are flocking there in droves, and it’s safe to say that the city’s lifestyle – all surfboards, smoothies, tacos, and Instagram irony – is setting the whole country’s tone.

Los Angeles is having quite a moment. Even people with zero interest in the film business are flocking there in droves, and it’s safe to say that the city’s lifestyle – all surfboards, smoothies, tacos, and Instagram irony – is setting the whole country’s tone.

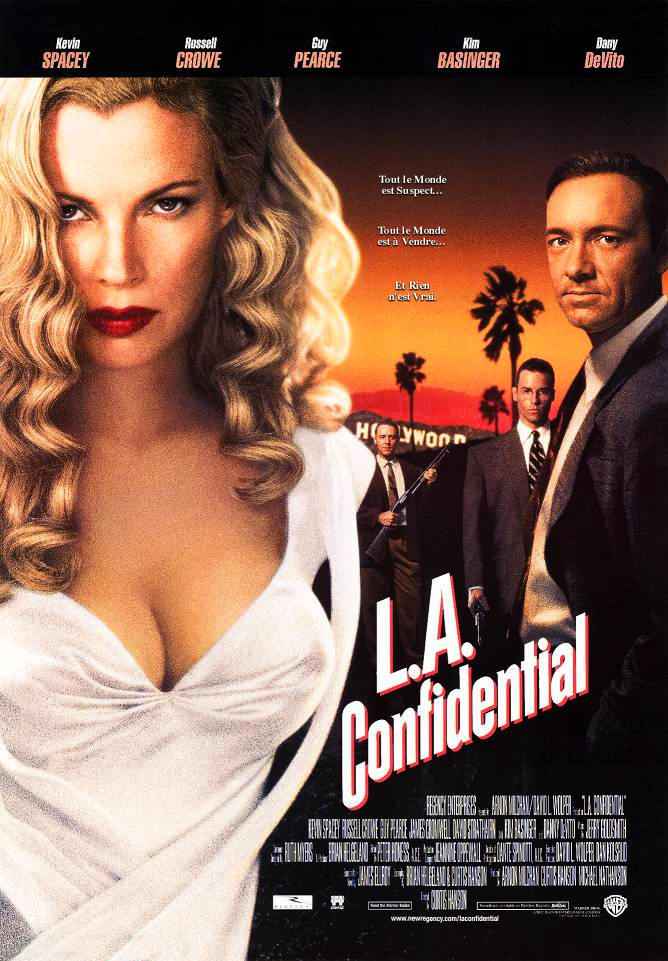

Also back in fashion: sunshine noir, which drags such dark matter as drifters, grifters, and serial killers into the light, usually as filtered by Southern California. Think P.T. Anderson’s “Inherent Vice,” the hit Amazon series “Bosch,” and, of course, the media’s rediscovered obsession with O.J. Simpson. It was only a few years after the former football star’s 1995 trial that writer/director Curtis Hanson adapted James Ellroy’s ultimate sunshine noir novel, L.A. Confidential, arguably the best sunshine noir of its decade. The 1950s-set thriller offered a much-needed historical perspective on the intersection of the LAPD, fame, and race, and was so smartly rendered that it launched the career of Russell Crowe, resuscitated that of Kim Basinger, and put SoCal vintage at the epicenter of fashion – paving the way for non-Tinseltown L.A. to occupy today’s zeitgeist.

Only twenty years old – it premiered May 14, 1997 – “L.A. Confidential” would never be fronted by a major distributor today, though Warner Brothers released it at the time. The film is too brainy, too beautiful, and too grown-up for comic book-addled studios to embrace. Chalk those brains up to Ellroy’s gloriously staccato prose and premise, which telegraphed nothing and delivered everything. A then-unknown Crowe (Hanson had to fight the studio to cast him) is an ideal Bud White, a 1950s thuggish Los Angeles cop who takes no prisoners and whose chief nemeses are wife beaters. Guy Pearce plays his other nemesis, Ed Exley, a self-righteous detective who takes no bribes, plants no evidence, and resists no career opportunities when it comes to selling out his colleagues. Rounding out the triptych is Jack Vincennes, also known as “Hollywood Jack.” Played by Kevin Spacey, Vincennes works Narcotics, is technical adviser for a “Dragnet”-like TV show called “Badge of Honor,” and is in cahoots with Sid Hudgens (Danny DeVito), the film’s narrator and  a reporter for Hush-Hush magazine (the 1950s equivalent of Us Weekly). Hudgens sets up public figures with drugs or prostitutes, then calls in Vincennes to make the busts and smile pretty for the camera. Even in voiceover, you can hear DeVito rubbing his hands together in glee. Like everyone but the grunting Bud, he speaks a mid-50s patois of Yiddish, Spanglish, and such punny slang as “prime sinuendo,” which makes me rub my hands in turn.

a reporter for Hush-Hush magazine (the 1950s equivalent of Us Weekly). Hudgens sets up public figures with drugs or prostitutes, then calls in Vincennes to make the busts and smile pretty for the camera. Even in voiceover, you can hear DeVito rubbing his hands together in glee. Like everyone but the grunting Bud, he speaks a mid-50s patois of Yiddish, Spanglish, and such punny slang as “prime sinuendo,” which makes me rub my hands in turn.

Though acutely at cross purposes, all four men stumble upon the same labyrinth of corruption, anchored by a huge shipment of heroin, the rape of a Mexican women by three men of color, a massacre at a diner, and a group of call girls surgically altered to resemble movie stars. It’s all too complex to synopsize neatly, which is a fact crucial to the film’s lurid appeal. Also crucial to that lurid appeal: Lynn Bracken, a prostitute decked out as Veronica Lake and played by Kim Basinger. Forty-three at the time, she’d never been more lovely nor self-possessed though she’s said she almost didn’t take the role because she was tired of hookers with hearts of gold. Though I don’t blame her – nor do I think the role really transcends those conventions – I’m glad she took it, if only because her composition of patience, red lips, satin curves, and long, pale hair and gowns is the pinnacles of 1990s beauty.

Style is really the saving grace of this crime thriller. In a swoon of cream and lemon Cadillacs, fedoras, and rat-a-tat-tat dialogue and gunfire, Hanson snags our attraction long before he gives cause to like any of his characters.  Though we’re saturated with a post-O.J. and Rodney King acknowledgment that cops mistreat suspects of color, the film perpetuates micro – and macro! – aggressions that would elicit greater eyebrow-cocking today. The only black characters are soda pop-swilling rapists and the only female characters are cocktail-swilling whores. Ellroy’s maze-like plot is pruned but not his rough bedside manner, and no one’s moral compass is revealed until the credits are practically rolling. Instead, the appeal of what is revealed lies in its unadulterated pack of lies–its glorious flourishes. At two hours and seventeen minutes, “L.A. Confidential” doesn’t just work; it soars. What’s more, it never stops picking at our fancies – unstacking gorgeous layer from gorgeous layer, de-realizing Hollywood dreams, and laying a path to the Los Angeles cinema inhabiting our imaginations today.

Though we’re saturated with a post-O.J. and Rodney King acknowledgment that cops mistreat suspects of color, the film perpetuates micro – and macro! – aggressions that would elicit greater eyebrow-cocking today. The only black characters are soda pop-swilling rapists and the only female characters are cocktail-swilling whores. Ellroy’s maze-like plot is pruned but not his rough bedside manner, and no one’s moral compass is revealed until the credits are practically rolling. Instead, the appeal of what is revealed lies in its unadulterated pack of lies–its glorious flourishes. At two hours and seventeen minutes, “L.A. Confidential” doesn’t just work; it soars. What’s more, it never stops picking at our fancies – unstacking gorgeous layer from gorgeous layer, de-realizing Hollywood dreams, and laying a path to the Los Angeles cinema inhabiting our imaginations today.

This was originally published at Signature.