Even a year ago, “Modigliani: Unmasked” at New York City’s Jewish Museum would not have been as timely, though its pleasures would have been just as assured. A showcase of Italian-Sephardic Jewish Amedeo Modigliani’s work as a sculptor and a craftsman, it revels in his defiant embrace of outsider status, and reminds us that extraordinary creative work can arise despite – and to spite – repressive political climates.

In 1906, when Modigliani emigrated from his native Livorno, an Italian port town known as a safe enclave for Jews, France was beset by nationalist anti-Semitism. Because of his fluency in French and Latin good looks, he might have been able to assimilate as a Gentile. Instead, as the Museum’s curatorial notes report, he’d introduce himself by saying: “My name is Modigliani. I am Jewish.” This exhibition, amassed mostly from the collection of patron and dear friend Paul Alexandre, shows the “artist as a young outsider,” exploring non-Western art and unpacking accepted notions of beauty in rough drafts and sculpture as well as a handful of completed paintings made between 1906 and 1914.

It’s shocking at first to examine Modigliani’s work stripped of colors. His palette is rich and rakishly appealing, an effect underscored in such signature paintings as “Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater” (1918-19). A portrait of the art student who would eventually become his wife, it is as amused as it is erotic – all tilted angles and spheres burnished by the atonal primaries that add flesh and blood to his hyper-stylization. In contrast, “The Jewess” (1908), one of his first exhibited paintings, is grounded out by wintry shades of sea and sky. Its model is most likely Maud Abrantès, his lover at the time, but the title is less of a valentine than a somber self-announcement. Throughout his career, Modigliani fiddled with eyes and noses – often blanking out the former and elongating the latter. Here, his subject’s eyes are piercing and green, and her nasal bridge is blocked out in white, the one symbolist flourish in an otherwise uncharacteristically naturalist portrayal. It’s as if the artist is pointing out the acute vision of his beloved, a fellow outsider, as well as the elegance of her nose – that Jewish facial feature most often by lampooned by anti-Semites. Throughout his career, there was something brilliantly subversive in Modigliani’s emphasis of the nose. To this Jew, schnoz was beautiful.

The exhibition, which encompasses most of the museum’s second floor, is divided into living-room-sized spaces that glide us through stages of his burgeoning artistic consciousness. (I hesitate to say radicalism, but only just.) The first gallery highlights early sketches and paintings, many featuring such social outsiders as séance conductors and cabaret and circus performers. All are chiefly influenced by Picasso’s “blue period” – more mood than structure. But the very early 20th century was a time when such European artists as Picasso, Gauguin, Matisse, and Brancusi had began to recognize the value of non-Western work, and in subsequent galleries we see how Modigliani followed suit.

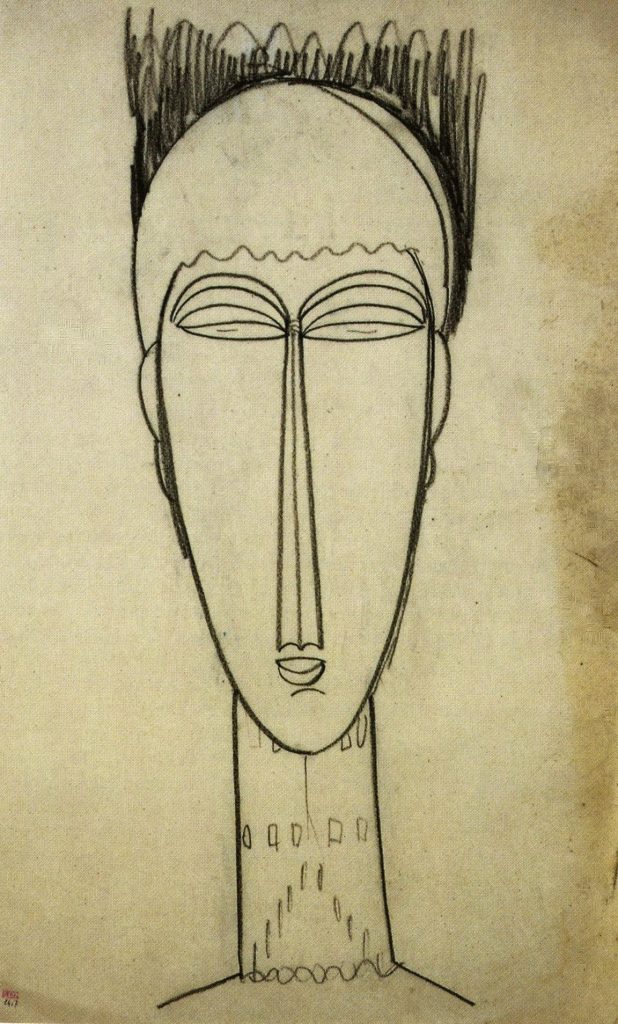

Interspersed with Modigliani’s increasingly abstracted drawings and limestone sculptures – carved heads, mostly – is a Fang-Ntumu mask from Equatorial Guinea, a mask of Gu from the Guro peoples in central Côte d’Ivoire, and an Egyptian statuette. The influences – the almond eyes, the symmetrical purity, the hyper-linear noses – are thus laid bare, often literally. And in his paintings and his caryatids – his unique, divine feminine-focused take on the architectural motifs – we see how he built upon these influences, telling as much by shape as by shade.

True, it can be argued that Modigliani was guilty of the same kind of cultural vampirism as his contemporaries – that he reduced other peoples’ artistic output to a vehicle for exploring his own subjugation.  But I sense more solidarity than fetishization in his work. As a Sephardic Jew, he may even have felt included in the African and Middle-Eastern diaspora.

But I sense more solidarity than fetishization in his work. As a Sephardic Jew, he may even have felt included in the African and Middle-Eastern diaspora.

Dead by 35, Modigliani is best remembered for his languorous female subjects – all attitude, these broads, with their saucy moues, haughty noses, jutting hips and chins. Sculpting became less viable as his lifelong physical challenges progressed, so we’ll never know how much deeper he may have dove into non-Western traditions had he not ultimately been limited to painting. But that undercurrent of disease weaves into his work as well, strengthening his identification with those living on the fringes of society, dislocating him further from traditional notions of beauty, and leading him to disembody female forms as he himself felt disembodied. It seems no mistake that these ladies are ultimately defined by essences rather than flourishes, for in Modigliani’s work spirit forever tips its hand. The Jewish Museum is to be commended for this resurrection of his own unruly spirit – his whimsical, fervent resistance.

This originally appeared at Signature.