Once when I was 12, I saved up my babysitting money and bought a ticket to hear Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” performed on George’s Island, a waterfront historical park located right off the coast of Boston.

Once when I was 12, I saved up my babysitting money and bought a ticket to hear Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” performed on George’s Island, a waterfront historical park located right off the coast of Boston.

I’d always been in love with that group of concerti, and my love had been as private as it had been absolute. My father was a resolute R&B worshipper and my mother bopped along to whatever he put on the turntable, slipping on Broadway musicals like “Gigi” when he wasn’t around. But I’d been a violinist since I was six; the Suzuki Method was huge in that era and both my factory-worker grandfathers had played ardently if unprofessionally. Playing classical instruments isn’t so common anymore but back then ordinary people of all classes and backgrounds did it all the time. I’ve been thinking about this, about how we used to make our own art and culture, didn’t just consume it like fast food.

By the time I realized I preferred the richer registers of the viola, my parents had already bought a grownup-sized violin–I was a tall kid–and my compromise was to practice just enough to justify their purchase. I played second violin in orchestra, and used my sight-reading skills more joyfully in chamber choir, where I sang first tenor. The result was a passion for the rigors of classical music that I rarely revealed at home or in my working-class neighborhood. Even now I rarely discuss this prediliction, though, left to my own devices, I listen to those busybody Baroque composers nearly as often as I listen to Aretha. Bach, Vivaldi, Dvořák; Telemann, too.

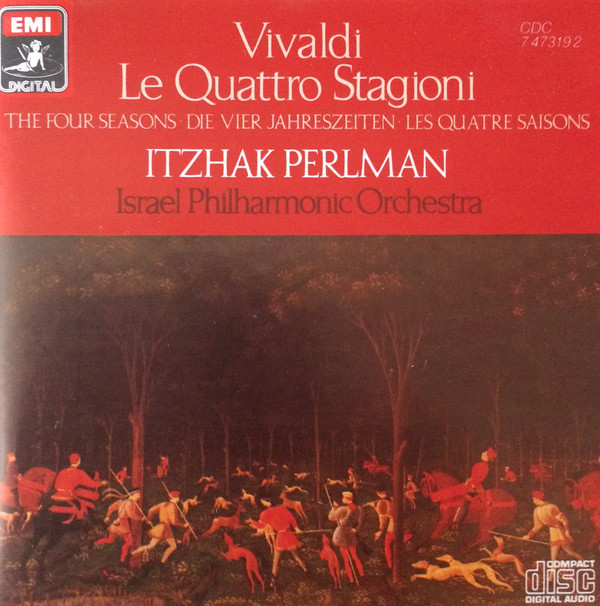

Alice, my mother’s mother, was hardly an austere woman but she shared my affinity for Bach, and we’d pass back and forth tape-cassette recordings of “Air” and the “Goldberg Variations.” It was Vivaldi who really straightened my spine, though. “The Four Seasons” was not exactly obscure fare –every other film soundtrack of the era seemed to feature “Spring” or “Winter”–but its voluptuous swells, running creek arpeggios, and lilting melodies, its brave march into nature’s wilds, lifted my heart above the pettiness and shabbiness that was the order of the day.

There were disadvantages of my childhood but growing up in Greater Boston never felt like one of them. Newton, my hometown–a small city, actually–was beautiful with its many ponds and creeks, wide fields and village squares, as well a few arthouse movie theaters. Though I lived in a then-working-class enclave, you could take Russian in our public school system, swim miles in local Olympic-sized pools. For longer than I’d played the violin, I’d made lists of how to cheer up  by making the most of the region, and I prided myself on checking off every item. Find a magic necklace at a yard sale? Check. Build a fort in the woods behind my neighbors’ house? Check. Find a secret hiding space in the deliciously dusty local library? Check. As I got a little older, the lists began to include public transportation, for I discovered that as long as I slid back into the house by dinner time, no one asked too many questions. Take the T to people-watch on Boston Commons: Check. Watch an Italian movie at the Coolidge Corner Cinema: Check. Take the bus to the Isabelle Stewart Gardner Museum and pretend it’s mine: Check. Convince a guard to participate in my game of pretend. Check!

by making the most of the region, and I prided myself on checking off every item. Find a magic necklace at a yard sale? Check. Build a fort in the woods behind my neighbors’ house? Check. Find a secret hiding space in the deliciously dusty local library? Check. As I got a little older, the lists began to include public transportation, for I discovered that as long as I slid back into the house by dinner time, no one asked too many questions. Take the T to people-watch on Boston Commons: Check. Watch an Italian movie at the Coolidge Corner Cinema: Check. Take the bus to the Isabelle Stewart Gardner Museum and pretend it’s mine: Check. Convince a guard to participate in my game of pretend. Check!

Back then, there were no such things as MP3s—Walkmen didn’t even exist yet–and so I often sang as I pursued my solitary adventures. For a very young person, I carried my sadness admirably, as if were a backpack full of treasures in addition to math workbooks. The “Four Seasons” seemed an ideal soundtrack for my pilgrim’s progress, as I called my adventures in a nod to the March girls.

The June night I attended “The Four Seasons” was warm and clear. I’d seen a notice about the concert in the Boston Globe, whose arts section I read every morning while my father read the sports page. I don’t remember asking anyone to accompany me, nor requesting permission to go into Boston at night. I simply sent away for a ticket with money I’d earned watching a scatological six-year-old down the block, and then, a good four hours before the concert, solemnly packed a sandwich, juicebox, and blanket, and walked the two miles to the T’s Green Line, from which I transferred to the Blue Line and then to a ferry. By myself I stood with the twilight and salty air streaming all around me, and it was as if I already could hear “Spring” playing in the wind.

When the boat arrived at the island teeming with war forts and lady ghosts, I followed the throng to Fort Warren Park. As I’d assumed would be the case, all the adults were too involved in their dates and wine and loaves of French bread to query why a tween– back then, we were called “preteens”– with dirty blond braids and a WGBH bag was walking alone in their midst. We settled on the ground and the musicians came out and tuned their instruments. At the horizon the darkening sky merged with the dirty water–it was Boston in the 1980s, after all–and into all that atmosphere soared my favorite piece of music, big and bounding in its tenacity and joy. On top of this I thrilled, closer to the stars than I’d ever been, closer to the past and maybe even the future. I clutched my sides and prayed to remember every second, every inch, every note.

back then, we were called “preteens”– with dirty blond braids and a WGBH bag was walking alone in their midst. We settled on the ground and the musicians came out and tuned their instruments. At the horizon the darkening sky merged with the dirty water–it was Boston in the 1980s, after all–and into all that atmosphere soared my favorite piece of music, big and bounding in its tenacity and joy. On top of this I thrilled, closer to the stars than I’d ever been, closer to the past and maybe even the future. I clutched my sides and prayed to remember every second, every inch, every note.

I had given this to myself, I knew, just as I knew I could one day give myself a lot more. No matter what shadows lived on the other end of my long journey home, I would forever have this quartet inside me, rising to greet an endless night sky.