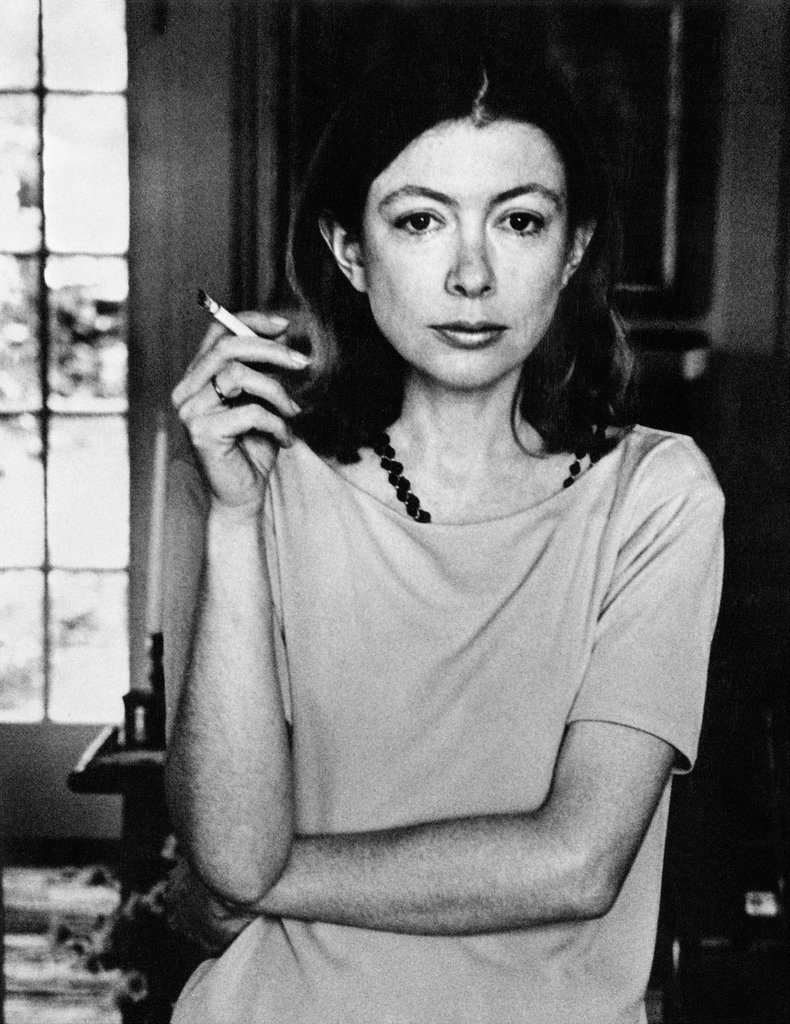

Eighty-three today, Joan Didion is inarguably old. But even in photos of the writer as a much younger woman, you can see something ancient and knowing that juxtaposes sharply with the youth culture of mid-twentieth century America. It’s a quality that distinguishes her work as much as her uncluttered, unflappable prose, and it makes her, to date, cinema’s most untapped natural resource.

Eighty-three today, Joan Didion is inarguably old. But even in photos of the writer as a much younger woman, you can see something ancient and knowing that juxtaposes sharply with the youth culture of mid-twentieth century America. It’s a quality that distinguishes her work as much as her uncluttered, unflappable prose, and it makes her, to date, cinema’s most untapped natural resource.

It’s surprising that more of Didion’s books haven’t been adapted to screen, especially since she has worked many times as a screenwriter, usually with her husband, the late author and journalist John Gregory Dunne. All in all, Didion and Dunne co-wrote at least eight screenplays – more, if you count the ones they reportedly massaged without credit. In 1972, they adapted her own book, Play It as It Lays, though she has said in interviews she wishes the resulting film were better. (Few disagree.) There also was the 1971’s druggie romance “Panic in Needle Park”; the extremely furry 1976 reboot of 1954’s “Star Is Born” (itself a reboot of a 1937 classic); and the 1996 Robert Redford-Michelle Pheiffer journalist romance “Up Close & Personal,” loosely based on the life and death of TV reporter Jessica Savitch. What’s most surprising is this filmography’s soapiness. With few exceptions, the story arcs go along the lines of: Couple falls in love, life caves in on couple.

Perhaps I should not be surprised by this emphasis on love and romance, for central to the glamorous intrigue cloaking the lady author is her marriage to Dunne, which she famously eulogized in the grief memoir The Year of Magical Thinking that she subsequently adapted to stage. (A screen version feels inevitable.) As the rest of America divorced and remarried and divorced again, Dunne and Didion presided over NYC and Hollywood shuffles as a golden couple writing reviews, nonfiction, fiction, and screenplays – usually in the same room. While Dunne was alive, I often wondered if the safety of that union both enabled and hampered her prose – if his bluster allowed for her remove. Certainly their interdependence rendered her even more of the Perfect Woman according to modern double standards. By his side, she reigned as the sort of lady who famously threw fantastic dinner parties at night after a day of writing brilliant, clean-edged prose. You just knew her purse contained no muss and no fuss – only lipstick, sunglasses, cigarettes, and keys to a lemon-yellow Corvette. This attention to detail rendered her such a behind-the-scenes icon that it’s surprising no one has made a biopic about her yet, especially as she’s drifted through nearly every American scandal of the last fifty years. From the Manson Family to Watergate, Didion’s love for seamless surfaces and seamy underbellies is Tinseltown to the core.

St. Joan has always alluded to great feelings, even great passions, but never in a way that threatens to disrupt her prose. No hysteria draws undue attention to individual paragraphs; no menstrual blood stains her “action verb, action verb” diction, as she refers to her literary style. She forever spurns the navel-gazing of her generation, and that lack of a psychoanalytical impulse translates into an ever-cooler, Hollywood-friendly remove, as well as an oddly masculine embrace of plot, movement, John Wayne types. Consider this paragraph from her 1968 seminal essay collection, Slouching Towards Bethlehem:

We went three or four times a week [to the movies], and there I first saw John Wayne… heard him tell a girl in a picture called War of the Wildcats that he would build her a house at the bend in the river where the cottonwoods grow and… deep in that part of my heart where the artificial rain forever falls, that is still the line I wait to hear.

Yearning yet muscular enough to balance her unabashed sentimentality, it mirrors – nay, summons – the tone of Golden Hollywood, and encapsulates Didion’s cinematic appeal as a muse and writer both. As does this line from “Goodbye to All That,” an essay from the same collection: “I cried in taxis and in Chinese laundries… and that was the year, my 28th, that I began to learn… that it is distinctly possible to stay too long at the fair.”

More lives in between her sentences and words than within them, and the effect is a delicate balance of melancholy and smooth self-assertion – clichés that don’t always seem like clichés, complements to Hollywood’s bright, subversive symmetry a la Douglas Sirk or, more recently, Todd Haynes. For that’s the thing, isn’t it? From “The White Album” to “Miami,” Didion’s books read as undiscovered mid-twentieth century films – all refined style and rough-hewn themes, unruffled surfaces and sublimated turmoil, and, always, always, dissociation rather than revolution.

Politically informed but mostly unaligned, spiritually and  ideologically fluent but doggedly unconvinced, it as if Didion doesn’t need her audience to like her so much as admire her. I’ll never pretend I’m not ambivalent about her, but I appreciate any woman who doesn’t sing for her supper, especially in the bloom of the #metoo revolution. Goodness knows I’m not the only one. Not only has the director and actor Griffin Dunne recently released “The Center Will Not Hold,” a documentary about his aunt, but an adaptation of her “A Book of Common Prayer” is currently in preproduction. (Hollywood son Campbell Scott is directing.) With its fascination with evergreen pasts and a newly found appreciation for female self-possession, cinema finally may be ready to embrace this sacred cow’s novels and essays.

ideologically fluent but doggedly unconvinced, it as if Didion doesn’t need her audience to like her so much as admire her. I’ll never pretend I’m not ambivalent about her, but I appreciate any woman who doesn’t sing for her supper, especially in the bloom of the #metoo revolution. Goodness knows I’m not the only one. Not only has the director and actor Griffin Dunne recently released “The Center Will Not Hold,” a documentary about his aunt, but an adaptation of her “A Book of Common Prayer” is currently in preproduction. (Hollywood son Campbell Scott is directing.) With its fascination with evergreen pasts and a newly found appreciation for female self-possession, cinema finally may be ready to embrace this sacred cow’s novels and essays.

This was originally published at Signature.