I first saw “The Exorcist” when I was 13 and home alone. This, of course, was a mistake. By the time Mike Oldfield’s iconic “Tubular Bells” ran over the credits, I knew I’d never sleep that night, or possibly ever again. But it was not just the circumstances in which I viewed this film that made it so terrifying. Forty-five years after its release, the adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s 1971 eponymous novel is still the most horrific of all horror movies, complete with a tween whose head spins backward.

I first saw “The Exorcist” when I was 13 and home alone. This, of course, was a mistake. By the time Mike Oldfield’s iconic “Tubular Bells” ran over the credits, I knew I’d never sleep that night, or possibly ever again. But it was not just the circumstances in which I viewed this film that made it so terrifying. Forty-five years after its release, the adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s 1971 eponymous novel is still the most horrific of all horror movies, complete with a tween whose head spins backward.

It’s a dark miracle that it was even made. At the time of publication, the book seemed unlikely to ever achieve a mass audience, let alone be adapted into the ninth highest grossing film of all time (when adjusted for inflation). Until then, Blatty, who also authored the screenplay, was best known as the comedy screenwriter who’d given us the Inspector Clouseau mystery “A Shot in the Dark.” A devout Catholic, he’d fictionalized a Jesuit priest’s account of a 1949 exorcism, but even his fancy Hollywood credentials couldn’t save it from being sent back to the publisher in droves. Only when a mysterious set of flukes landed him on the Dick Cavett Show for a full 45 minutes did the “The Exorcist” catapult to the New York Times best-seller list. It remained there for 57 weeks.

When it came to adapting the book to screen, all the bigwig directors of the time were approached, Stanley Kubrick included. But no one bit but Friedkin, who’d just nabbed a best-director Oscar for 1971’s “The French Connection.”

Though I’ve always admired horror as a film genre– it reveals more about our collective unconscious than any shrink or sociologist ever could– I’ve never found it especially scary. Violent, yes. Glamorously macabre, yes. But scary? I’m more frightened by white supremacists or climate change — real life, in other words. But William Friedkin’s 1973 masterpiece frightens precisely because it does feel like real life. Channeling cinéma vérité, it feasts upon everything fetid in our culture then and now: Freud, corrupt leadership, economic inequality, dysfunctional nuclear families, and misogyny, not to mention the Catholic Church. (Writer-director Jordan Peele’s “Get Out” strikes different but just as profound cultural chords.)

mention the Catholic Church. (Writer-director Jordan Peele’s “Get Out” strikes different but just as profound cultural chords.)

Ellen Burstyn plays Chris, a film actress who, with her red cap of hair and charming impatience, is loosely based upon Shirley MacLaine, Blatty’s neighbor at the time. Along with her 12-year-old daughter Regan (Linda Blair), Chris cozily perches in a townhouse in Washington, D.C., where she’s on location. The specter of Nixon looms, though he’s never mentioned by name.

At first Chris and Regan are beset only by the sort of problems plaguing a wealthy single mother and her kid. A living American Girl doll, Regan has a nanny, butler, and cook, and is the subject of magazine features, but her development is clearly arrested by an absentee dad who doesn’t even get in touch on her birthday. (In a scene straight out of 1978’s “Kramer Vs. Kramer,” a defeated-looking Regan eavesdrops on Chris screaming at an operator who can’t connect a call to her overseas father.) Snub-nosed and pony-tailed, Blair plays out her burden perfectly–wheedling for a horse, batting her curly lashes as her mother tucks her into bed, cooing in a much younger child’s voice.

Then there’s “Captain Howdy,” Regan’s imaginary friend whom she accesses through a ouija board discovered in the basement. When I was growing up, my mother had only one rule: “Don’t mess with ouija boards.” She wasn’t kidding, and she wasn’t wrong. But not privy to my mom’s excellent advice, Chris gently accommodates her daughter’s flirtation with the occult, and strange occurrences begin: mysterious rustlings in the attic, shaking beds, flickering lights. By the time Regan hijacks a dinner party by peeing on an expensive rug and growling at a visiting astronaut, “You’re gonna die up there,” it’s clear trouble’s afoot.

Part of the genius of this film is how it contextualizes evil in the complacency of mid-twentieth century America.  Alarmed by how her daughter is “acting out,” Chris consults Western medicine, which subjects the girl to a battery of painful tests and procedures. Though she’s now growling in a demonic hiss and engaging in full-on telekinesis, a doctor dismisses her symptoms as hyperactivity, the predecessor of today’s ADHD. “Would hyperactivity cause the whole bed to shake?” Chris asks, and he barely disguises his condescension. Only when bedroom bureaus hurtle in the air and Regan sexually assaults her male examiners do they diagnose her with a brain lesion that, hmmmmm, “just isn’t turning up on scans.” Finally an exorcism is suggested — but only, doctors hasten to add, to disabuse the tween of the notion that she’s been possessed.

Alarmed by how her daughter is “acting out,” Chris consults Western medicine, which subjects the girl to a battery of painful tests and procedures. Though she’s now growling in a demonic hiss and engaging in full-on telekinesis, a doctor dismisses her symptoms as hyperactivity, the predecessor of today’s ADHD. “Would hyperactivity cause the whole bed to shake?” Chris asks, and he barely disguises his condescension. Only when bedroom bureaus hurtle in the air and Regan sexually assaults her male examiners do they diagnose her with a brain lesion that, hmmmmm, “just isn’t turning up on scans.” Finally an exorcism is suggested — but only, doctors hasten to add, to disabuse the tween of the notion that she’s been possessed.

She’s never said she was.

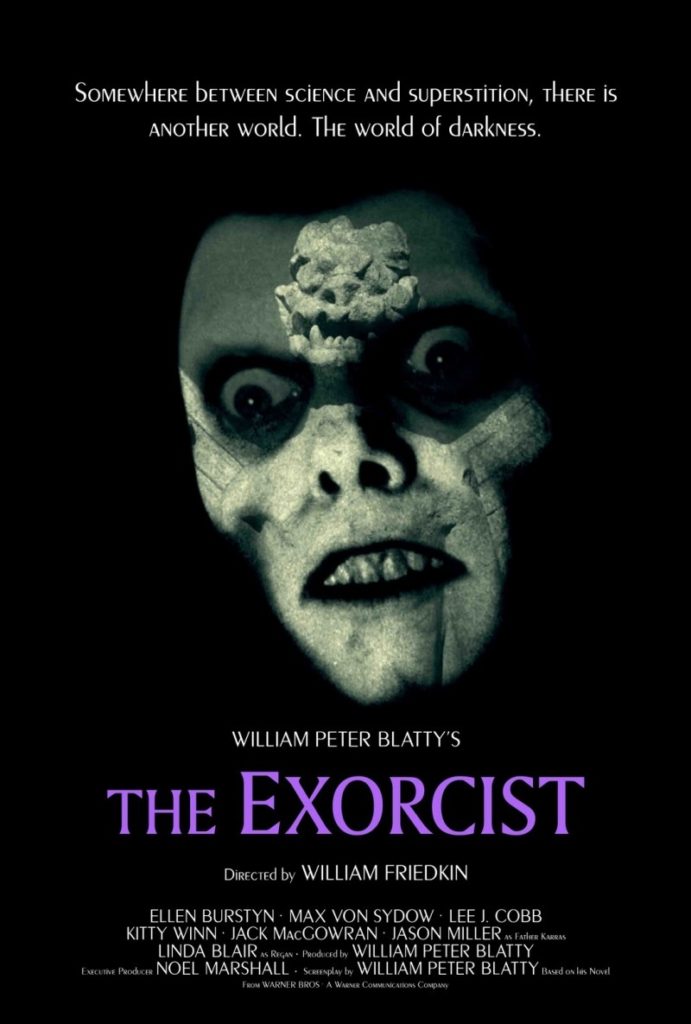

It is as this point that the Church is finally called in. One emissary is Father Damien Karras, a Harvard-educated psychiatrist played by Jason Miller with a beautifully hunted melancholy. The father of Jason Patric and former son-in-law of Jackie Gleason, Miller had just won a Pulitzer Prize for his class-conscious play “The Championship Season” but had never acted in a film before. Ever a casting genius, Friedkin saw Miller’s gritty gravitas as necessary for the conflicted priest, arguably the heart of the story. It’s no coincidence that the subliminal imagery of the demon, all high cheekbones and hollow eyes, looks an awful lot like Miller.

When Karras’ mother dies sick and alone in a crumbling New York tenement, he dreams she has descended into a NYC subway–leave it to the “French Connection” director to conflate the MTA with hell–and the priest realizes he has lost his faith. So much so that he dismisses Chris’s request for an exorcism with the usual mental health jargon. “To do one, I’d have to send the girl back to the sixteenth century,” he says, explaining that medicine has replaced demons with paranoia and schizophrenia. Such a brush-off doesn’t sit well with a woman whose child has taken to masturbating with a giant crucifix while commanding her mother to perform cunnilingus on her bleeding, torn vagina. “That thing is not my daughter!” Chris screams.

Even in the face of gas-lit patriarchy, a mother knows.

Above all a product of 1970s cinema, “The Exorcist” leans hard on natural light, chiaroscuro, and skepticism. More similar to “Deliverance” and “Serpico” than other horror films, its unconcealed blemishes, wrinkles, and sagging jowls–its yellowing teeth and gallows humor–earns our faith. The first time the formerly cherubic Regan appears in her possessed incarnation— sore-mottled green and yellow skin, matted hair darkened by grease and vomit, feeding tube attached to her nose, pupil-less eyes– the impact is  profound. Even her once-lilting singsong is supplanted by radio actress Mercedes McCambridge’s gravely bark. When Chris discovers the demon in her child has killed a man, it snarls: “You know what she did? Your cunting daughter?”

profound. Even her once-lilting singsong is supplanted by radio actress Mercedes McCambridge’s gravely bark. When Chris discovers the demon in her child has killed a man, it snarls: “You know what she did? Your cunting daughter?”

Holy unholy!

It’s almost inevitable that Max von Sydow would step in as Father Merrin, the older Jesuit exorcist. A veteran of Bergman’s spiritual crisis dramas, the actor’s hulking pathos cuts right though all that Georgetown equivocating. Only 44 at the time, he was painted as a much older man by legendary makeup artist Dick Smith; even von Sydow’s hands, veiny and tremulous, look as ancient as the Devil himself. It’s a visual effect akin to Chris’s morph from movie-star glam to the babushkas and prim collars of an Old World refugee. An Underworld refugee.

The ending of “The Exorcist” may be too pat — the demon hurtles into Karras who hurtles to his death — but the satisfaction it denies us reads as a refusal to let audiences get complacent. In a scene included only in a director’s cut, Merrin declares: “The girl is not the real target. The rest of us are. I think the point is to make us despair, to make us feel…God doesn’t love us.”

To say “The Exorcist” hits home would be a grand understatement. Its intimation of a spiritual void–an ancient chaos lurking right below modernity’s slick surfaces, its chirpy banality–extends beyond the confines of the screen. There are the nine people who died during the making of the film, as well as the mysterious fire delaying production for six weeks. Upon the film’s Christmas release, viewers suffered seizures, violently threw up in aisles, reported mental disturbances. With its blood-soaked sexual and linguistic profanity, the R rather than X rating (which would’ve prevented a widespread audience), also seems a dark miracle.

As much I like to focus on love and light, I’ve come to believe in possession, at least in the sense that  that nature abhors a vacuum. Negative energy —evil, yes — tends to colonize narcissistic voids and neglected souls. This was true in 1973, when the nation was under immoral leadership (there’s a reason the film is set in Nixon-era D.C.), and it applies today, with our current administration preying on Americans’ worst impulses and our environment and economy in tatters.

that nature abhors a vacuum. Negative energy —evil, yes — tends to colonize narcissistic voids and neglected souls. This was true in 1973, when the nation was under immoral leadership (there’s a reason the film is set in Nixon-era D.C.), and it applies today, with our current administration preying on Americans’ worst impulses and our environment and economy in tatters.

Humanity always needs exorcists, be they witch doctors or films that shatter unearned complacency. That’s why “The Exorcist” haunts us still.

This was originally published at Signature.