The first time I saw Schindler’s List, it enraged me.

The first time I saw Schindler’s List, it enraged me.

Admittedly, this was not a typical response. Upon its release 25 years ago, the film was touted as the crowning glory of director Steven Spielberg’s career and 1993’s greatest cinematic achievement. At the Oscars that year, the adaptation of Thomas Keneally’s historical novel about true-life figure Oskar Schindler won seven Academy Awards, including Spielberg’s first for best director.

It wasn’t just that the 3-hour-and-16-minute film was expertly crafted. Though documentaries like “Night and Fog” (1955) and “Shoah” (1985) had already catalogued the ravages of the Third Reich, Spielberg’s feature about a German industrialist who saved more than a thousand Polish Jews ignited younger generations’ commitment to “never again” just as Holocaust survivors and witnesses were beginning to die out. In a 2013 interview, the director said, “The shelf life of ‘Schindler’s List’ has renewed my faith that films can do good work in the world.”

Really, as an introduction to both the horror and the goodness of which humans are capable, it was the ultimate Spielberg vehicle. And that was my problem in a nutshell. As the film’s credits rolled and people around me sniffed, I stormed out of the theater, saying, “Leave it to Spielberg to find the feel-good story of the Holocaust.” Not yet a critic (I was still in school), my reaction was profoundly personal. I am the descendant of Jews from Krakow, where this film is set, and my family line was nearly eradicated as a result. The film was bound to make me cry and bound to hit too close to home for me to forgive any Hollywoodizing of one of the most monstrous chapters of the 20th century and my ancestral line.  By the time that infamous image of a little girl’s red coat punctuated the film’s painterly cinematography, I was positively foaming at the mouth.

By the time that infamous image of a little girl’s red coat punctuated the film’s painterly cinematography, I was positively foaming at the mouth.

I see the film differently now. Whereas a quarter-century ago I only recognized Spielberg’s saccharine manipulation, now I register how carefully he built his case using the exact tools for which my younger self faulted him.

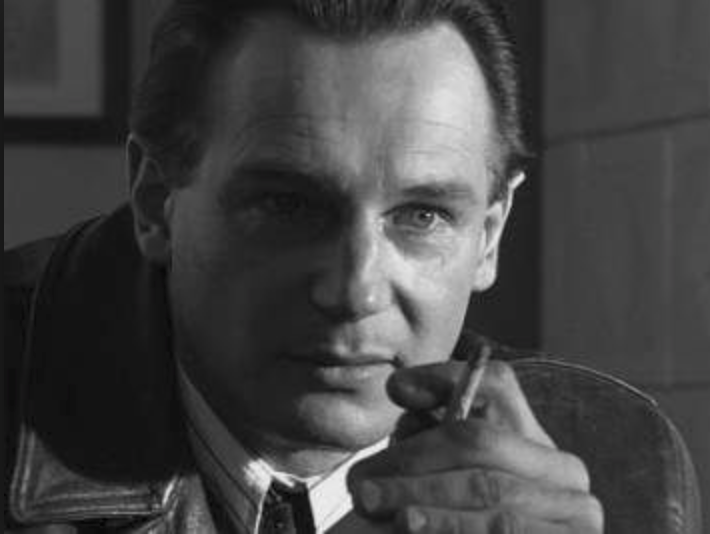

Perfectly cast as Schindler, larger-than-life Liam Neeson embodied the playboy entrepreneur who initially viewed Hitler’s Germany as a unique way to make big bucks; scenes of the Nazi Party member’s decadence were intercut with the brutality Jews were subjected to even before the Camps. Sure, when he opened a Krakow factory to make goods for the German war effort, he enlisted the help of a Jewish accountant (Ben Kingsley, all flashing eyes and sealed mouth). But even the German’s embrace of the accountant is mercenary rather than merciful: the Jew’s simply the best for business.

The rest of the story: After Germany moved Polish refugees to the city, madman Nazi officer Amon Goth (Ralph Fiennes) was enlisted to build a local concentration camp. Hiring the Polish Jews as cheap labor, Schindler felt moved to protect his workers from being sent to their deaths in Auschwitz after witnessing the Nazis’ larceny first-hand.

Even in 1993, we’d seen Nazis like Goth on screen before: dangerous, hateful psychos. But Germans like Schindler — ones whose immunity to crimes against humanity stemmed from greed, not hatred — had not yet been properly indicted. Schindler’s List showed us what happens when ordinary people stop heeding any moral compass — when they behave like frat-brothers at a kegger, Wall Street bankers, Donald Trump’s enablers and acolytes. It was a necessary glimpse.

Even in 1993, we’d seen Nazis like Goth on screen before: dangerous, hateful psychos. But Germans like Schindler — ones whose immunity to crimes against humanity stemmed from greed, not hatred — had not yet been properly indicted. Schindler’s List showed us what happens when ordinary people stop heeding any moral compass — when they behave like frat-brothers at a kegger, Wall Street bankers, Donald Trump’s enablers and acolytes. It was a necessary glimpse.

What’s most haunting are the recurring images of Jews getting shot in the head. It’s a one-armed, old man’s punishment for inefficient shoveling. It’s the retribution for a female Jewish engineer who informs her labor-camp commander that a barracks is being built on a faulty foundation. (Her advice is posthumously heeded.) It….just is. The murders take place as casually and unpredictably as children step on ants–as instant gratification rather than part of any master plan. The shock they deliver is a brilliant inversion of the sort of thrill that always has been the director’s signature.

Yes, Spielberg indulged some of his worst impulses. Schindler’s redemption is too fetishized, especially in a seemingly endless soapbox of a final speech, and that red coat still irks the hell out of me, especially in its lofty reference to cinema’s beloved red balloon.

Yet 25 years later I also can see how the director marshaled his technical and storytelling proficiency to reckon with one of modern history’s darkest periods. The claustrophobia of his hand-held shots boosts the impact  of the wide pans of the Camps, and Janusz Kaminski’s black-and-white, beautifully textured cinematography blends with newsreel footage to render these events as visceral rather than mythical. Michael Kahn’s deft editing unpacks the horrors in real time, and John Williams’s score, sharpened by Itzhak Perlman’s violin, pierces our sorrow. The script by “Searching for Bobby Fischer” writer-director Steven Zaillian is a coup of restraint, pacing, and world-building. Even the characters’ two-dimensionality (a Spielberg failing on his best day) helps us grapple with the “everyman” qualities of the Nazis and the Jews. Underscoring the message that we can become perpetrator as easily as we can become victim, “Schindler’s List” is vital in Trump’s America.

of the wide pans of the Camps, and Janusz Kaminski’s black-and-white, beautifully textured cinematography blends with newsreel footage to render these events as visceral rather than mythical. Michael Kahn’s deft editing unpacks the horrors in real time, and John Williams’s score, sharpened by Itzhak Perlman’s violin, pierces our sorrow. The script by “Searching for Bobby Fischer” writer-director Steven Zaillian is a coup of restraint, pacing, and world-building. Even the characters’ two-dimensionality (a Spielberg failing on his best day) helps us grapple with the “everyman” qualities of the Nazis and the Jews. Underscoring the message that we can become perpetrator as easily as we can become victim, “Schindler’s List” is vital in Trump’s America.

This was originally published at Signature.