All the interesting characters I’ve ever worked with–including myself–have had at their center a feeling of otherness, of homesickness. And it’s wonderful to watch someone finally open that forbidden door that has kept him or her away. What gets exposed is not people’s baseness but their humanity. It turns out that the truth, or reality, is our home.

All the interesting characters I’ve ever worked with–including myself–have had at their center a feeling of otherness, of homesickness. And it’s wonderful to watch someone finally open that forbidden door that has kept him or her away. What gets exposed is not people’s baseness but their humanity. It turns out that the truth, or reality, is our home.

But you can’t get to any truths by sitting in a field smiling beatifically, avoiding your anger and damage and grief. Your anger and damage and grief are the way to the truth. We don’t have much truth to express unless we have gone into those rooms and closets and woods and abysses that we were told not to enter. When we have gone in and looked around for a long while, just breathing and finally taking it in–then we will be able to speak in our own voice and to stay in the present moment. And that moment is home.--Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird

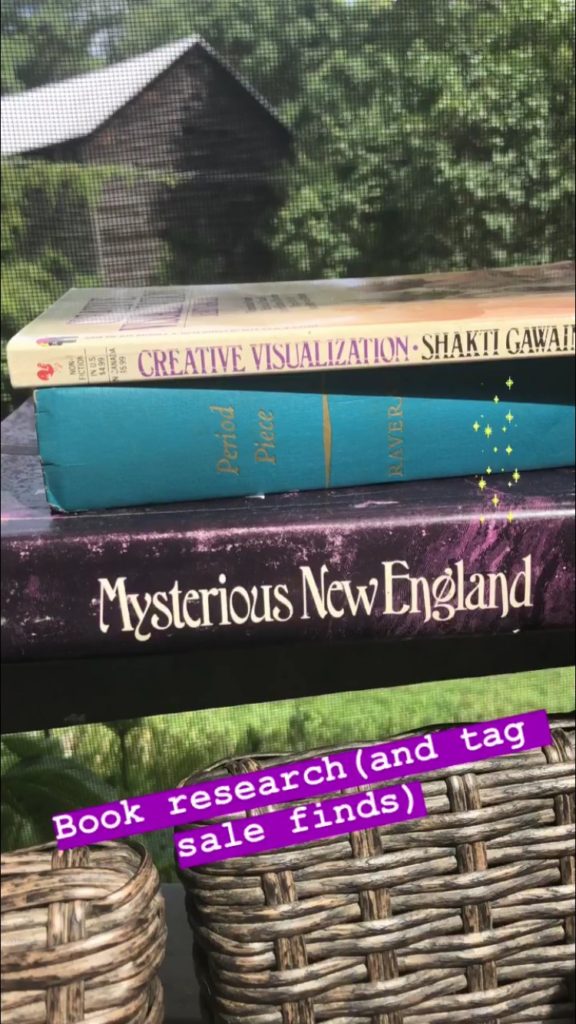

I am still upstate and spent last Saturday with music pouring out of my car speakers while I wound through great green and gold roads, indigo hills rising in the foreground, wildflowers waving hello. Ostensibly I was tag-saling (tag-sailing!), and in fact scored better than I usually do. Mostly, though, I was seeking a small adventure in the netherland between Columbia County, New York, and the Berkshires–between my chosen state and home state, respectively. I experienced my usual thrill when I saw the “Welcome to Massachusetts” sign, and my usual frustration when confronted with the parsimony of people from my native state. “One dollar, twenty five cents,” announced the older white man with shark eyes and shaking hands as I showed him the wares I wished to purchase at a church rummage sale. “So much?” I said, and flashed the lipsticky grin that opens all kinds of doors on the island of Nueva Berserk. “Now, where are you from,” he said slowly, and I could just tell he was wishing he’d charged me one hundred dollars and twenty five cents.

The Massachusetts fear of outsiders, of difference of any sort, is so strong that even when I was growing up in Greater Boston people used to ask me suspiciously, “Now, where are you from?” It wasn’t just that my sort of blowsiness differed from the thin lips and small upturned noses that passed for prettiness around those parts. And it wasn’t just that I wore bright colors and clashing patterns–none of that LL Bean and Red Sox gear that passes for New England style. It was that I was theatrical–naturally show-boating, if you want to know the truth. And if there’s one thing Massholes hate, it’s overt airs. People there may be as status-seeking as they come, but they’ll be damned if they’ll admit it.

By the time I got rid of my Boston accent to do a national kid’s TV show, locals treated me with the same disdain they’d beam at any interloper. For this reason and ones more charged I left my homestate for good at age 18. That defection defines me as much as the fact that I am a half Jew, a queer feminist, a single lady with a cat.

As I made my way back to Hudson I drove unusually carefully. The week before I’d gotten my first ever speeding ticket. My permakitten had projectile-vomited on me on the Taconic Parkway, and as I’d raced to an exit ramp to clean up, a state trooper had pulled us over. With the ticket he handed me a cup of purified water for Grace, as well as an advisory about her welfare. “Take her to an animal hospital,” he’d said. “That smell isn’t right.”

Duh, I thought, resenting his bland officiousness. It’s puke. In Boston, the cop would have let me off while joking about my cat being the Exorcist.

And so it goes. Much as I pick at the scabs of relationships gone wrong, I can’t help but long for my native land, then cringe when I’m there.

The next day my car tire blew out–I mean, the thing was toast–and since we were still in the shadow of Mercury Retrograde I lost my bank card to boot. The thing was, the autoshop manager was from Danvers, Mass, where my great-grandmother once ruled the roost, and while he worked on my car he and I played the name game, not to mention the Massachusetts dozens–you know, where you mock the shit out of each other in lieu of hugging. When I realized the card was gone, the guy–who was my age, which meant we called each other “kid” the whole time he ragged on my slobby car–spent 30 minutes combing the area until he found it beneath my passenger seat. (My permakitten’s explosion seemed to have rearranged all the atoms in my permacar.)

That’s the thing about being from Massachusetts. You can take the kid out of the state but you can’t take the Masshole out of the kid.

Obstensibly I’m in Hudson to tackle the second-to-last part of my book–the sad part, when people started to die and I realized I was literally not just figuratively on my own. The part when I realized I wasn’t going to survive unless I skipped town. I’ve been avoiding this section since the spring, and writing it gives me a stomachache to rival Grace’s on the Taconic.

I feel so sorry for myself that the self-pity malingers even as I gaze upon this lush visage a kind friend has afforded me, even as so many good people have supported me in this 24-month mountain trek of authoring a memoir.

It makes me think of this guy I enountered on the MTA the week before I left NYC. It was rush-hour and sticky-hot and everyone smelled terrible and was simply fuming, what with everyone else’s elbow and backpack in their face. This big dude plopped next to me–chinos straining, red face sopping, and decked out in a Yankees shirt and hat, which is a transgression I’ll never forgive no matter how long I live in NYC.

(One of our elementary schoolyard chants: “I love New York but I hate the Yankees.”)

Wouldn’t you know this guy widened his legs so that he wasn’t just man-spreading but men-spreading? I mean, it was just him and me on a part of the bench that normally would seat three people, and he still was squeezing me out.

“Not worth a fight,” I told myself, and plugged in my earbuds. But even over Stevie singing “All in Love Is Fair,” I could hear the terrible cry of an infant. Such a cry pierces everything, doesn’t it? You want it to stop not just to save yourself but to end the great suffering of a being too small to be responsible for keeping their counsel. I pulled off my buds and scanned the jampacked car for the tiny person in question. There were a few infants to be seen but, true New Yorkers already, they were calmly regarding the Bosch spectacle of the subway car as if it were a panther at the zoo–awesome, terrifying, contained.

So where was this baby in distress? From the sound of it, the little one was in real trouble, sick or injured, maybe getting abused in real time.

It took me a very long time to synthesize what my ears and eyes were already telling me. That the Yankees-loving giant with no spacial boundaries was the person emitting this cry. His face was screwed up, his shoulders were heaving, and he was weeping–nay, he was bawling. Not the silent tears most New Yorkers have shed somewhere along a subway line but the un-self-conscious shriek of a child lost in the wilderness of his discomfort and grief. It was an alarm clock of snot and spittle.

Finally, I rubbed his arm a little and said, “It’s going to be ok.” Not, “are you ok?” because he clearly wasn’t. And he sniffed, managed a small smile before surrendering to a fresh gale of tears.

Finally, I rubbed his arm a little and said, “It’s going to be ok.” Not, “are you ok?” because he clearly wasn’t. And he sniffed, managed a small smile before surrendering to a fresh gale of tears.

I wasn’t sure if he really was going to be okay. His homesickness was palpable–audible–and it was clear he was no more at peace in his pain than he was on this subway or in this Yankee-loving town. But he’d stopped faking the funk–there was no pretending for him now–and by opening that door, he’d invited us into his anguish and our compassion. He’d made it possible for all of us, himself included, to welcome his true self in.

The question now plaguing me as I navigate these bonny backroads: Can I open that door? Can you?